Search this site

‘Exiled To Nowhere’: Photographer Documents Life Inside the Camps and Ghettos for Burma’s Muslim Rohingya

Rohingya from Sittwe and the surrounding districts have not been permitted to attend Sittwe University since the violence two years ago in 2012. The University is located in teh same area as the Rohingya IDP camps. Burmese police stand guard at the entrance of Sittwe University to ‘protect the students’.

Rohingya from Sittwe and the surrounding districts have not been permitted to attend Sittwe University since the violence two years ago in 2012. The University is located in teh same area as the Rohingya IDP camps. Burmese police stand guard at the entrance of Sittwe University to ‘protect the students’.

Small clinics created by non-profits tend to hundreds of sick Rohingya each day but can only provide basic healthcare and cannot meet the needs of 130,000 people in the camps. Exhausted and dehydrated, 8-year-old Nurul (right) waits with over 150 others (mostly women and children) to see a doctor at a clinic near Thet Kay Pyin IDP camp.

Small clinics created by non-profits tend to hundreds of sick Rohingya each day but can only provide basic healthcare and cannot meet the needs of 130,000 people in the camps. Exhausted and dehydrated, 8-year-old Nurul (right) waits with over 150 others (mostly women and children) to see a doctor at a clinic near Thet Kay Pyin IDP camp.

In western Burma, state crime experts warn that a genocide may be unfolding. Since June 2012, numerous bouts of violence between Buddhist and Muslim communities have forced more than 140,000 ethnic Rohingya Muslims into camps and ghettos, from which they are forbidden to leave. The crisis of the past two years is the latest in a campaign of persecution by the Burmese government and ethnic Rakhine Buddhists in western Burma that has rendered the Rohingya stateless. Thousands leave the country each year on boats bound for Thailand, Malaysia and beyond. Many drown en route. Bangkok-based photographer Greg Constantine has spent years documenting stateless communities around the globe. His latest book, ‘Exiled To Nowhere: Burma’s Rohingya,’ was published in 2012. Here are some images from his visit to the camps in western Burma in July.

Over 650 Rohingya children pack into the primary school in Yan Thei village. The school has only 6 teachers who share 4 small blackboards. After the violence in oct 2012, the village has received no government assistance for education or healthcare.

Over 650 Rohingya children pack into the primary school in Yan Thei village. The school has only 6 teachers who share 4 small blackboards. After the violence in oct 2012, the village has received no government assistance for education or healthcare.

What do you see as the main driving factors in this conflict?

“What people need to understand is that at the heart of it, this isn’t a new story. The recent conflict in Rakhine isn’t something that just started in the summer of 2012. There is a historical legacy of persecution against the Rohingya community in Rakhine that dates back decades. Framing this as a religious issue of Buddhism vs. Islam belies its complexity. Instead we see ethnic Rakhine staking a claim for political space and natural resources and ‘protecting’ and ‘defending’ their identity. Add strong elements of racism, discrimination, the complete failure of anyone inside Burma to seek realistic solutions, the interests of self-serving politicians looking at elections in 2015, and the self-serving interests of the international community into the mix, and you have what is happening right now – an entire community consisting of hundreds of thousands of people, namely the Rohingya, being treated as if they are not even human.”

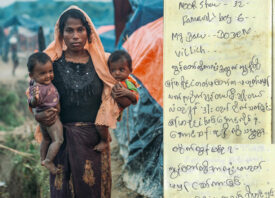

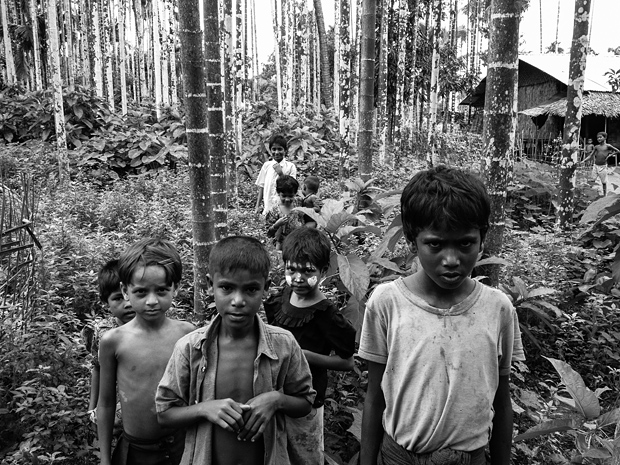

The ancient temple complexes of Mrauk-U are visted by tens of thousands of tourists each year, yet not even five miles away almost the entire Rohingya village of Yan Thei was completely destroyed on Oct 23, 2012. Over 400 homes were burnt to the ground as Burmese police stood by and watched. A group of children stand among the betel nut palm trees in Yan Thei village.

The ancient temple complexes of Mrauk-U are visted by tens of thousands of tourists each year, yet not even five miles away almost the entire Rohingya village of Yan Thei was completely destroyed on Oct 23, 2012. Over 400 homes were burnt to the ground as Burmese police stood by and watched. A group of children stand among the betel nut palm trees in Yan Thei village.

What changes have you noticed over the several visits you made to Rakhine?

“The first trip I made was in November 2012, soon after the second wave of violence. Back then, Rohingya refugees were shell-shocked, but while conditions in the camps were horrible, there seemed to be a sense that their displacement was temporary and they might return home soon. On my second trip in March 2013, the mood had changed and there was a growing sense that they wouldn’t be able to return home, so a lot of boats, many over-packed and rickety, were leaving for Malaysia. This time I an alarming increase in police and army personnel operating in the camps. And the structures in which Rohingya are living now are not temporary. There are very few huts and tents. Most people are living in line-row houses built by the government. These may look better than the tents, but the very troubling thing for me is that conditions now indicate that this is much more of a permanent situation. This is incredibly scary and tragic because there are few signs that anyone in the international community, and indeed politicians in Burma like Aung San Suu Kyi, has the backbone to do anything to force or convince the government or the political powers in Rakhine State to change.”

Entry and exit to the last inhabited Rohingya neighborhood in the city of Sittwe is not permitted, except for two times every week when an armed convoy of 2-3 trucks carrying Rohingya and limited supplies to/from the IDP camps to Aung Mingalar. A police truck prepares to carry 20 Rohingya from the IDP camps to Aung Mingalar in central Sittwe.

Entry and exit to the last inhabited Rohingya neighborhood in the city of Sittwe is not permitted, except for two times every week when an armed convoy of 2-3 trucks carrying Rohingya and limited supplies to/from the IDP camps to Aung Mingalar. A police truck prepares to carry 20 Rohingya from the IDP camps to Aung Mingalar in central Sittwe.

Is there something particular you’ve been trying to do with your photography on this visit? Why the use of Instagram?

“On this trip more than others, I constantly found myself internally saying, “these camps are the closest thing I have ever seen to a concentration camp.” There aren’t mass killings happening in the camps, but the level of control, oppression, deprivation, humiliation I sensed was overwhelming. I found myself focusing on new themes like the police presence. The use of Instagram came to mind as a way to make the work I produced on this trip more immediate to people. The work I’ve done on the Rohingya already has received a lot of exposure, but I want to present the work in a way that can help people better understand this story. I have five high-profile exhibitions of my Rohingya work slated to take place in Yogyakarta, Kuala Lumpur, NYC, Geneva and Istanbul over the next 9 months and the work from this trip will make a huge and very important contribution to these exhibitions. For me on this recent trip, I think Instagram was a really effective tool to use and has added to the other ways I’m trying to share the work with a larger audience.”

Abdul (67) has been sick for months and only receives basic paracetamol. For several reasons, he has not been able to travel to Sittwe to see a proper doctor. Healthcare in the camps is at a critical level since many international NGOs were forced to stop operating in the camps in early 2014.

Abdul (67) has been sick for months and only receives basic paracetamol. For several reasons, he has not been able to travel to Sittwe to see a proper doctor. Healthcare in the camps is at a critical level since many international NGOs were forced to stop operating in the camps in early 2014.

Are you finding photography to be an effective method of transmitting the extent of the crisis in western Burma?

“I’m a photographer and I use photographs to tell stories. I totally believe in photography when it comes to human rights issues like this. We all have different roles when it comes to these sorts of issues. I have a pretty good sense of where my boundaries are in terms of my own professional capacity to contribute to the documentation, exposure and better understanding of the story of the Rohingya and what is going on in western Burma. That said, I believe that for people to have a better understanding, they need to see. And I believe visual evidence is a vital component to sparking any sort of change, however small that change might be. I’ve been working on the story of the Rohingya now for 9 years. I started my project ‘Exiled To Nowhere: Burma’s Rohingya’ in early 2006. I want my photographs to provide a visual documentation of these past 9 years just as much as I want it to (and hope it will) reinforce the need for action and change to a story that, unfortunately, just gets worse and worse every year.”

After a monsoon rain, Hakim (61) takes a short break at a stand selling betel nut hear Dar Paing IDP camp.

Why has this burst to the fore during a supposed time of democratic transition?

“Is there a transition happening in Burma? How deep is this transition everyone talks about? I think there are any number of explanations why this story has received the attention it has received. The mistreatment of Rohingya in Thailand and Malaysia has helped elevate the story, just confirming that this is also now a regional problem. But what people need to keep remembering is that, again, at the heart of it, this isn’t a new story. For years, there was almost no attention given to the Rohingya. As for Burma’s transition, has it made a difference in the lives of the majority of people inside Burma’s border? It definitely hasn’t for the Rohingya!”

The presence of Burmese Police and Army encampments inside the IDP camps have increased in the past year. Police patrols are present throughout the camps. In the early morning as Rohingya travel from one IDP camp to the next, a unit of the Burmese Police run riot drills in a field located in the middle of the IDP camps.

The presence of Burmese Police and Army encampments inside the IDP camps have increased in the past year. Police patrols are present throughout the camps. In the early morning as Rohingya travel from one IDP camp to the next, a unit of the Burmese Police run riot drills in a field located in the middle of the IDP camps.

130,000 stateless Rohingya in Burma have lived in apartheid-like existence in isolated displacement camps since communal violence between the Buddhist Rakhine community and the Muslim Rohingya community in June 2012. Most camps once consisted of huts and tents were replaced by hundreds of more permanent line-row buildings. Rohingya say the buildings are sign that their stay in the camps is no longer temporary. A woman walks through Say Tha Mar Gyi camp.

130,000 stateless Rohingya in Burma have lived in apartheid-like existence in isolated displacement camps since communal violence between the Buddhist Rakhine community and the Muslim Rohingya community in June 2012. Most camps once consisted of huts and tents were replaced by hundreds of more permanent line-row buildings. Rohingya say the buildings are sign that their stay in the camps is no longer temporary. A woman walks through Say Tha Mar Gyi camp.

Rohingya man walks past the empty building of an MSF health clinic in Shan Taung village outside of Mruak-U. The Burmese government forced MSF to stop all overations in the Rakhine State in early 2014. MSF was the primary provider of all healthcare to Rohingya in Mrauk-U and throughout Rakhine.

Rohingya man walks past the empty building of an MSF health clinic in Shan Taung village outside of Mruak-U. The Burmese government forced MSF to stop all overations in the Rakhine State in early 2014. MSF was the primary provider of all healthcare to Rohingya in Mrauk-U and throughout Rakhine.