Search this site

Powerful Portraits of Life (and Death) in Hospice Care

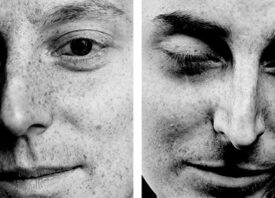

Horst Kloeters, 25 August

Horst Kloeters, 30 August

Ulrike H. lived her final months in Room 23 at St. Frances Hospice near Dusseldorf, Germany, watching as people came in and out of the facility–as they died. A longterm resident of the hospice, Mrs. H had been a dance instructor before she was hit with what she called the “bad luck” of ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), a disease that results in the atrophy and inability to control muscle movement.

Over the course of a year, German photographer Daniel Schumann got to know the woman, capturing her portrait as the illness progressed. The photographer’s book, Purple Brown Grey White Black – Life in Death documents the lives of nine residents at St. Frances, including Mrs. H; its title, says Schumann, comes from the colors of the sweaters she wore on each consecutive visit.

Schumann carried out his civil service at St. Frances, but years after his the mandatory work ended, he felt himself pulled once more to the hospice and its residents. With help from his contacts within the staff, he distributed previous images from his portfolio and invited individuals to participate. Everyone he photographed was lucid and well enough to make an informed decision, and although some immediately responded “yes” or “no,” many took days to mull it over before agreeing.

Each person’s motivations were different; some appreciated the company, while others like Mrs. H found that the portraits helped to express to family members the emotional ups and and downs that come with living in hospice care. Most understood that soon they would die, and like Wolfgang Petersmann, were grateful for the opportunity to show the world just what that meant.

The ward Schumann visited had eight rooms, each of which could be personalized to suit its the person who lived there. For some, like Ingrid Willenbrink, this meant transforming the space entirely with cherished tokens and memorabilia. In addition to three nurses on staff, the residents were visited by volunteers and family members with whom they could chat, take a walk, play games, and read books. They had meals cooked especially for them and were medicated to eliminate discomfort as much as possible. In many ways, the hospice was a second home, although some longed to return to where they had lived their lives previously.

The photographer was there for the deaths of seven of the people pictured in Purple Brown Grey White Black, all of whom he depicts both living and deceased. Photographing individuals after their death was a way of giving himself closure–of driving home the fact that these people had passed away, of accepting it, and of saying farewell. “It was important for me to see their faces again,” he says of those who died, noting that in death, all the stress and suffering of illness had been washed away, revealing shades of a person’s character that were lost in pictures taken during their final days.

Since he got to know some of these people intimately, the process of watching them die could be a painful one, but the hope of giving them comfort was what ultimately pushed the photographer to continue for an entire year. Purple Brown Grey White Black, stresses Schumann, is not about the ebbing of life or the deterioration of the body.

Instead, he strives to picture death merely as an element of life, something that is at times feared but remains nonetheless inescapable for us all. He chose to photograph for exactly a year so as to represent the changing of the seasons; as summer fades to fall, so too does life pass into death. It is significant that the book closes with a living woman, Gertrud Neumann; although individual people cease to exist, life continues.

Schumann didn’t pressure his sitters to tell him any more than they did naturally; he was there to listen if they had something to say, or as he would put it, “to just be there.” Meeting these people has taught the photographer as much about the strength of the human spirit as it has the fragility of the body; sometimes, a dying person would cling to life just long enough to say goodbye to a loved one, at which point they would allow themselves to slip away.

Ulrike H., whom the photographer names his “main character,” lived through the entire year he was there, watching the world outside her window through what he describes as “bright, lively eyes.” She passed away a few months later. Of his year at the hospice, Schumann writes, “I learned for myself that a seemingly small thing like a warm autumn day is something precious.”

Buy Purple Brown Grey White Black – Life in Death here.

Ulrike H., 17 February

Wolfgang Petersmann, 23 February

Wolfgang Petersmann, 15 March

Ulrike H., 23 February

Margarete Hagemann, 28 February

Margarete Hagemann, 7 April

Ulrike H., 15 March

Sigrid Kessler, 15 March

Sigrid Kessler, 30 March

Ingrid Willenbrink, 25 March

Ingrid Willenbrink, 14 May

Ulrike H., 24 March

Hildegard Kohler, 5 July

Hildegard Kohler, 7 August

Ulrike H., 19 December

Gertrud Neumann, 17 February

All images © Daniel Schumann