Search this site

Take a Peek at the Larry Sultan Retrospective at SFMOMA

Larry Sultan, Business Page, from the series Pictures From Home, 1985; chromogenic print.

Larry Sultan, Business Page, from the series Pictures From Home, 1985; chromogenic print.

Larry Sultan, Practicing Golf Swing, from the series Pictures from Home, 1986; chromogenic print.

Larry Sultan, My Mother Posing for Me, from the series Pictures From Home, 1984; chromogenic print.

Home is a state of mind as much as it is a place. For some it can be a four-letter word of the very worst kind—or it can be synonymous with love. Home can be so many things, all of them deeply personal.

For photographer Larry Sultan (1946-2009), home was where he created work, lush images of suburban California that are as American as Hostess cupcakes. There’s something delightfully unnatural about it all, something that comforts us with soothing visions of a naïve faith in the possibilities of the contrived. Here, the element of control reveals itself, that deeply seductive belief that we run this.

The SFMOMA is currently showing Here and Home, a retrospective of 200 photographs from Sultan’s 35-year career, now through July 23. The exhibition is drawn from four different series that defined Sultan’s career: Evidence (1975–77), made collaboratively with Mike Mandel, comprises found pictures from archives of research institutions and corporations sequenced evocatively; Pictures from Home (1983–92), a study of his parents’ life in the suburbs of L.A. and in their retirement community in Palm Desert, California; The Valley (1997–2003), documenting the porn industry in the San Fernando Valley, where suburban homes are rented for film shoots; and Homeland (2006–09), which features photographs of day laborers hired to enact familial, everyday rituals in the suburbs of Northern California.

Sultan’s photographs of home and family are a study in the construction of identity and appearances, and the way these inform our ideas about storytelling, offering a provocative comment on photography itself and our desire to capture and preserve a memory for future reference. Much in the same way that memory is not entirely accurate, Sultan’s photographs suggest a tension between reality and interpretation. Here the photograph, always a creation, takes on an autobiographic twinge, invoking aspects of Sultan’s own history infused into his work.

Growing up in the San Fernando Valley, Sultan’s early years were filled with he shiny, happy aesthetic of Baby Boomer suburbia and its implicit social dynamics, which were predicated on the newly homogenized customs and middle-class aspirations of White America. Located just outside Los Angeles, the Valley was the setting for countless television shows and movies, all a sort of affordable mid-century modern that evoked the ethos of catalogue consumerism. Anyone could look just like the people on TV, if they were so inclined. In this aesthetic, that strangely soothing feeling returns and an urge for Jell-o fruit salad and Brady Bunch re-runs overwhelms.

Here is “home,” as it impressed upon so many of us—who were in the confines of whatever it is our situation was, watching the television in search of something better. Even if we had it good, we might want something more, like the perfectly straight mane of Marcia Brady or Mike Brady’s perm. Whatever that something might be, Sultan captures it with ease—as well as a sense that everything is not entirely what it seems. Comfortably uncomfortable, he lures us in to his world.

The telling irony of the Valley is that it went from the image of wholesomeness to something else—the strangely banal backdrop for porn shoots before the Internet changed the game. Here, in Sultan’s photographs at the height of professional porn, we see the trappings of suburban America embodying what would soon become a whole new norm. In this milieu, the idea of home becomes a bit disconcerting, becoming a place to act out intimacies in exchange for a fee—reminding us prostitution is not illegal so long as you tape and distribute the goods for profit.

Perhaps this is the natural outgrowth of the suburban ideal, of the image of catalogue-aesthetics made real. When everything is for sale, what remains? Where is home when you can hire day laborers to pose in pictures that exist nowhere else? Of course they have their own photos but undoubtedly, they are far more casual and authentic to the moment, thus would not be considered art—unless maybe someone “found” them and went the appropriation route.

In the end, Sultan’s work offers far more questions than answers, making you feel some type of way. Like you know there’s horse-hooves in Jell-o but you eat it anyway.

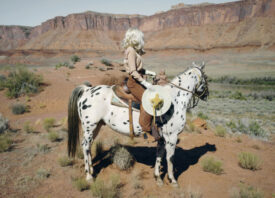

Larry Sultan, Backyard Hercules, from the series Homeland, 2009; chromogenic print;

Promised gift of Nion McEvoy to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Larry Sultan, Discussion, Kitchen Table, from the series Pictures From Home, 1985; chromogenic print.

Larry Sultan, Boxers, Mission Hills, from the series The Valley, 1999; chromogenic print.

Larry Sultan, Sharon Wild, from the series The Valley, 2001; chromogenic print.

Larry Sultan, Batting Cage, from the series Homeland, 2007; chromogenic print;

Promised gift of Michal Venera to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

All images: © Estate of Larry Sultan. Photos courtesy Casemore Kirkeby and Estate of Larry Sultan.