Search this site

Celebrating “The Sweet Flypaper of Life” in Roy DeCarava’s Centennial Year

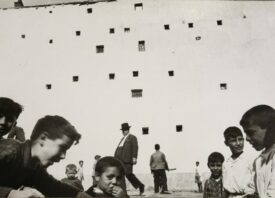

Roy DeCarava, Boy in park, reading, 1950

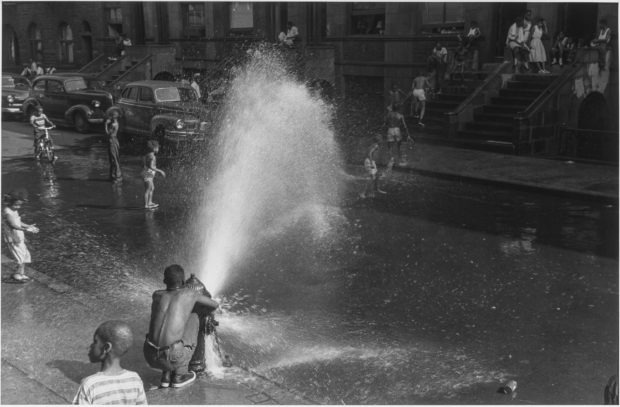

Roy DeCarava, Swimmers, 1950

“We’ve had so many books about how bad life is, maybe it’s time to have one showing how good it is,” Langston Hughes said of The Sweet Flypaper of Life, his landmark art book collaboration with Roy DeCarava recently republished by David Zwirner Books.

In 1952, DeCarava became the first African-American photographer to win a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship. He used the one-year grant of $3,200 to make the photographs that would appear in the book, a tribute to Harlem glowing in the final years of its legendary Renaissance.

DeCarava gave Hughes a selection of prints from which the poet wrote the story of Mecca through the eyes of Sister Mary Bradley, a fictional grandmother who knows everybody’s business and will put you on if you listen.

Hughes begins the story when Sister Mary refuses to follow the messenger of the Lord with a telegram calling her home. She had many reasons to stay, the first she revealed was to “see what this integration the Supreme Court has done decreed is going to be like.”

She had plans, Hughes revealed, to visit South Carolina before she died. But since she’d been up North? Well, Sister Mary had the tea on everyone and graciously invited you in for a cup.

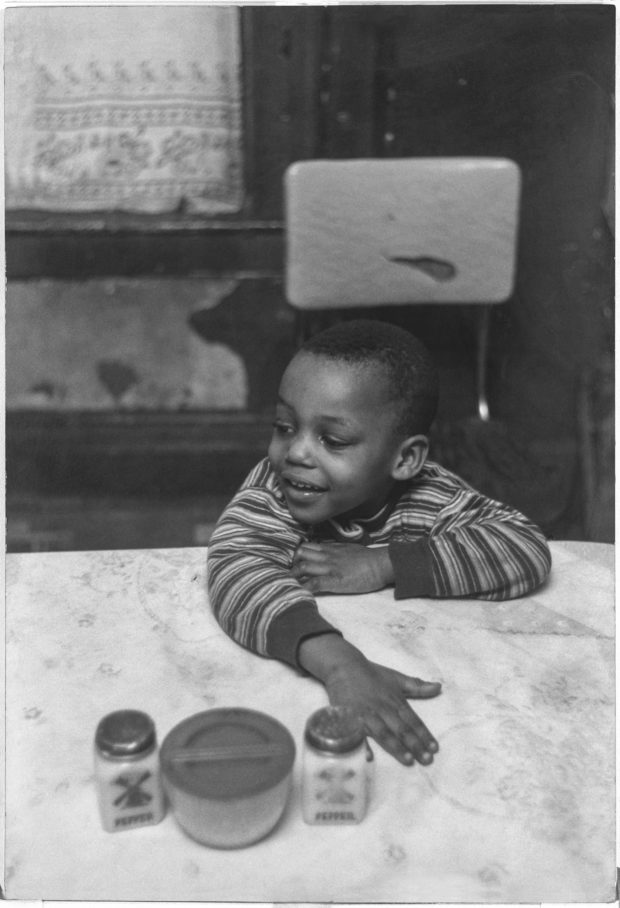

In his resonant prose, Hughes gave voice to the characters that DeCarava captured on the streets and in the homes in Harlem, revealing their relationships and inner lives just as sure as one who has lived the to tell the tale. Hughes’s resonant prose gives form and shape to the complex inner lives of DeCarava’s subjects, giving them nuance and depth, making them feel as real and alive now as they did then.

The Sweet Flypaper of Life is the story of Black love: of family and community, of life and death, of the rich textures in the tapestry of daily life that forms our sense of self and the bonds we bear on this earth.

DeCarava died 10 years ago this October, just shy of 90. In this, his centennial year, his work speaks to the significance of being the architect of your own destiny to create the world in which you want to live.

Born in New York and raised by his mother, Elfreda Ferguson, a Jamaican immigrant, who separated from DeCarava’s father shortly after he was born, DeCarava inherited his mother’s love for art. One of the few Black students attending the Cooper Union School of Art, DeCarava left after two years of enduring racism from white students.

Photography became a means to DeCarava to shape a new style of work, one which spoke to the realities of being Black in White America and rejecting the framework of outsiders as his own.

“One of the things that got to me was that I felt that Black people were not being portrayed in a serious and in an artistic way,” DeCarava told The New York Times in 1982, as he looked back on the inspiration to create The Sweet Flypaper of Life.

For DeCarava, Black folks were not the subject of scientific study, political propaganda, or otherwise objectified as was the practice of the establishment. Rather, Black folks simply are, in and of themselves.

“I do not want a documentary or sociological statement,” DeCarava wrote in his Guggenheim Fellowship application. Rather, the photograph was “a creative expression, the kind of penetrating insight and understanding of Negroes which I believe only a Negro photographer can interpret.”

It is a way of seeing and engaging with the world, one that makes Sister Mary run and go tell that — to me, you, and to God. It is a legacy befitting a man who changed what a photography book could be.

Roy DeCarava, Joe and Julia singing, 1953

Roy DeCarava, Little Jerry at table, 1953

Roy DeCarava, Woman and puppy, 1951

Roy DeCarava, Man sitting on stoop with baby, 1952

Roy DeCarava, Picketers, 1950

Roy DeCarava, Stickball, 1952

Roy DeCarava, Woman walking above, New York, 1950

All images: © The Estate of Roy DeCarava ?2018. All rights reserved. Courtesy David Zwirner

Further reading: Photographers Celebrate Black History, from the 1920s to Now