Search this site

Photographer Henk Wildschut Investigates Food Production in the Netherlands

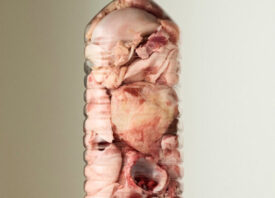

Examined. In 2012 the animal welfare organization Wakker Dier (‘Animal Awake’) launched a campaign against industrially bred broiler chickens. Wakker Dier gave this breed the name ‘plofkip’ (chicken fit to burst) because of its rapid growth within six weeks from a chick to a 2.3 kilo bird, having consumed exactly 3.7 kilos of feed to get there. The chicken in the photograph is getting a health check from a vet at the request of Wakker Dier.

When I was asked two years ago to make an in-depth study of the subject of Food for de RijksMuseum in Amsterdam, I was full of preconceptions about the food industry. I saw it as dishonest, unhealthy and unethical. More than that, it was contributing to the decline of our planet, unlike in the good old days, and I felt that the magic word ‘organic’ was going to solve everything. So when I embarked on this project, my first impulse was to bring to light all the misunderstandings about food once and for all.

After two years of research and photography, I realized that the discourse on food production can be infinitely refined and that this often puts supposed advantages and disadvantages in a new light. Scaling-up can actually enhance animal welfare, for example, and organic production is not always better for the environment. Often, an excessively one-sided approach to the subject of food is a barrier to real solutions. Food is simply too wide-ranging and complex a subject for one-liners or to be describing in terms of black and white.—Henk Wildschut

Dutch photographer Henk Wildschut enters a world of debate and controversy, documenting the modern processing and production of our food. After spending extensive time with those who handle the day-to-day management of various animals and plants, Wildschut concludes that the entire issue of demand, population growth and government regulation is far more complicated than the general public understands. Shot in a clinical but thoughtful method, Wildschut presents us with the facts that are before him, refusing to take up an agenda or make direct comment on what we see.

Food was recently published as a photo book, full of further stories and images from Wildschut’s research.

Semi-finished. With brown poultry it is possible to breed a variety that makes a visual distinction between a hen and a cock. A young female is brown and a young male white. This difference is essential at a hatchery for layer chickens, as males don’t lay eggs.The selection process is now less complicated and can be carried out by eye by non-specialized staff. Using a conveyor belt, 20,000 brown and white chicks can be separated every hour.

Sexing. As for white poultry, there has been no success as of yet in achieving a clear visual distinction between the sexes. A specialized external firm is enlisted to sex these chicks. The difference can be read off in the wing feathers. One specialist can sex 25,000 chicks a day. The male chicks are carried off on a special production belt to the gassing unit.

Feces. After three weeks in the Patio module, the chicks–now a full 700 grams–are carried by a conveyor belt to the ‘ground floor’, where within three weeks they will grow to 2.5 kilos. After each cycle, the two levels are washed and disinfected. Once the manure is removed, the whole area is cleaned with a detergent and later thoroughly disinfected with a sprinkler. The process of cleaning takes three days for the Patio module and two days for the ground floor.

-196 C. A bull produces an average of 480 doses per approved ejaculation. A popular bull can supply up to 300,000 doses in its lifetime. Each such dose is collected in a straw. The straws are stored in liquid nitrogen at a temperature of -196 degrees Celsius. Every beaker holds 3000 straws. Altogether there are some 600,000 straws in a container. The colour, together with a code, name and date, makes each straw unique.

-196 C. A bull produces an average of 480 doses per approved ejaculation. A popular bull can supply up to 300,000 doses in its lifetime. Each such dose is collected in a straw. The straws are stored in liquid nitrogen at a temperature of -196 degrees Celsius. Every beaker holds 3000 straws. Altogether there are some 600,000 straws in a container. The colour, together with a code, name and date, makes each straw unique.

Washing. The veal industry took off in the Netherlands at the end of the 1960s as a response to the growth of the dairy industry, which had created a surplus of calves. The Ekro slaughterhouse processes 350,000 calves a year and is the world’s largest veal producer.

Collecting. A calf’s liver has an average weight of 4.5 kilos and after removal of the carcass it cools off to 1 degree Celsius within 24 hours. The racks speed up the cooling process and prevent damage to the delicate organ tissue.

Collecting. A calf’s liver has an average weight of 4.5 kilos and after removal of the carcass it cools off to 1 degree Celsius within 24 hours. The racks speed up the cooling process and prevent damage to the delicate organ tissue.

Quarantine. The smoking compartment in the canteen is there to combat infection. Staff are not allowed to leave the building during working hours. The company is hermetically sealed off from the world at large to minimize the risk of infection. There is overpressure throughout the interior to ensure that polluted air is kept out

Growth. Sweet pepper producer De Wieringermeer grows red, yellow and green sweet peppers on a 40-hectare site. The colour is determined by the stage of the ripening process (green is unripe, red is ripe). The plants grow between 5 and 10 cm a week. The red-and-white ribbon marks off a compartment of one hectare. This division into hectares gives a good understanding of the growth process among young plants; the work can then be planned accordingly.

Growth. Sweet pepper producer De Wieringermeer grows red, yellow and green sweet peppers on a 40-hectare site. The colour is determined by the stage of the ripening process (green is unripe, red is ripe). The plants grow between 5 and 10 cm a week. The red-and-white ribbon marks off a compartment of one hectare. This division into hectares gives a good understanding of the growth process among young plants; the work can then be planned accordingly.

2,400 m2. Torsius has a total of 120,000 laying hens. Besides the standard free-range birds the hatchery has a further 5700 organic laying hens. At Torsius there is no need to debeak the chickens; the barns are minimally lit with special high-frequency strip lighting so that the chickens are kept calm. They also have enough distractions and enough room to move. Stressed-out chickens tend to peck others, something that happens a lot less at Torsius. Torsius produces about 100,000 eggs every day, putting it in the major league among hatcheries.

Pasture. The Brandsma Dairy Farm is a dynamic-organic company of 55 cows and 25 sheep. Brandsma is widely known as an ‘ear-tag objector.’ For them, ear tagging is a violation of the animal’s integrity. After 20 years of legal wrangling, these farmers are allowed to register their animals using the traditional I&R method, that is, hide brands and other surface marks. For six months in the year, Brandsma’s cows have free access to the pastures around the barn. For the product to qualify as pasture milk, the cows need to graze outdoors for 120 days a year, 6 hours a day.

Lavatory. Research on Pigsy, a toilet for pigs, began in 2012. A pig usually looks first for a place to sleep and then–at a comparatively great distance away–a place to defecate. Piglets are trained early on to relieve themselves in a special corner of the shed. A major advantage is that the feces can be collected and removed in a shorter time. This lowers the level of ammonia emissions in the shed, the advantage for the farmer being that there is no further need for air washers.

Shower. Paul Steenbekkers is manager at one farm, Ven/Heide, where they keep 1700 sows and 3300 piglets. Paul works from 7:30 in the morning until 10 past four in the afternoon. All staff and visitors are required to take a shower before entering the farm and don a complete set of company clothes. These strict rules on hygiene have meant a reduction in the use of antibiotics in recent years of 70%. The administering of antibiotics was a preventive measure until 2009.

Shower. Paul Steenbekkers is manager at one farm, Ven/Heide, where they keep 1700 sows and 3300 piglets. Paul works from 7:30 in the morning until 10 past four in the afternoon. All staff and visitors are required to take a shower before entering the farm and don a complete set of company clothes. These strict rules on hygiene have meant a reduction in the use of antibiotics in recent years of 70%. The administering of antibiotics was a preventive measure until 2009.

Export. To avoid the fish becoming dehydrated they are coated in a glaze solution. The deep-frozen fish are then drawn through a shallow layer of water. This treatment, which is sometimes done repeatedly, adds to the weight of the fish so that more can be sold for less.

Infusion. By optimizing plant growth conditions—the ideal mix of water, light, nutrition, CO2 and temperature—PlantLab seeks to revolutionize plant cultivation. According to PlantLab, this way plants produce up to 10 times more than in a regular greenhouse and use something like 90% less water. And there are no pesticides involved. A plant treated this way proves to be no longer susceptible to diseases and epidemics.

This post was contributed by photographer and Feature Shoot Editorial Assistant Jenna Garrett.