Search this site

Poignant Portraits and Stories of Sexual Assault Survivors

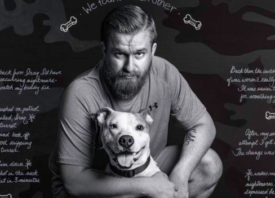

New York-based photographer Lydia Billings opens a dialogue about rape and recovery in her series Trigger Warning. After the assault of a dear college friend, Billings began to photograph the locations and victims of rape as a means to cope with her own helplessness and horror over the event. Each image is a heart-wrenching reminder that physical violence can happen anywhere and to anyone. One woman’s very personal mission has now become a fierce passion, beginning a conversation about the painful and lasting nature of sexual assault. Billings speaks with us about how she navigates a trauma so devastating and her fervor to have the survivors’ stories be heard.

Images, locations and stories are not correlated with one another to protect the survivors.

A young high school student is excited about his new boyfriend. The two are ridiculed at school, and find it easiest to show affection elsewhere. During lunch period, they often drive to a nearby parking lot to talk and enjoy the view of the town below. Despite conversations about waiting until they’re both ready to start experimenting with sex, the boy’s boyfriend forces him to perform oral sex one afternoon in the car.

A young high school student is excited about his new boyfriend. The two are ridiculed at school, and find it easiest to show affection elsewhere. During lunch period, they often drive to a nearby parking lot to talk and enjoy the view of the town below. Despite conversations about waiting until they’re both ready to start experimenting with sex, the boy’s boyfriend forces him to perform oral sex one afternoon in the car.

Trigger Warning tackles a brave and sensitive subject. Where did the idea for the work originate and how did you go about beginning the project?

“In 2010, a dear friend from my childhood, Rorie, was raped at her college. We were living in separate cities, attending different universities, and I desperately wanted to be with her. I felt utterly helpless in supporting her healing and recovery, which was especially troubling to me because I’d always thrived as a supporter of my loved ones.

“Though I had heard about it growing up, my understanding of rape was extremely basic and any discussion at home or at school surrounding sexual assault was minimal. Until Rorie’s rape, I had no true comprehension of how destructive and devastating sexual assault could be.

“I continued to struggle with my feelings of helplessness for months. In an effort to begin tackling my own questions and misunderstandings surrounding rape, I began to make photographs. At first, my images were timid and fearful; I had no knowledge about the affects of surviving a rape. I began reading everything I could find related to rape, rape culture, victim blaming, sexism, feminism, historical figures, social trends, rape myths, suggested femininity & masculinity, advertising, school sex education, and more. I discovered other artists and writers working hard and making strides on similar issues.

“I spent a lot of time writing and reflecting on my research and personal understanding(s) of the world around me and my communities’ contributions to a rape-promoting culture. I met and spoke with rape survivors who were ready and willing to share their stories with me, at first primarily as a means of self-education.

“I had a strong desire to photograph places where rape had occurred in my neighborhood and beyond, but had trouble getting my hands on local police reports, which contained the information I needed. I decided to photograph assorted landscapes and locations, which could serve to represent spaces where rape had occurred. These photographs exist in the project today. From there I began photographing survivors after several months of shooting landscapes. The two sections fed into and through each other and continue to exist in a dialogue of sorts. Each informs the other.”

On a crisp summer evening, a teenage girl was kidnapped, sexually assaulted, and left along the edge of this small river. Her body was found a number of days later, and her attacker remains unidentified.

On a crisp summer evening, a teenage girl was kidnapped, sexually assaulted, and left along the edge of this small river. Her body was found a number of days later, and her attacker remains unidentified.

How did you find young women and men to speak so honestly about such a personal experience? Is the dialogue and portrait session cathartic for them?

“I meet my subjects primarily through word of mouth. I’m constantly sharing information about Trigger Warning with colleagues and friends, and often people will indicate interest or mention that someone they know has survived a rape or assault. Often, I share a business card or my email address to pass along, which sometimes leads to email contact or an inquiry on the Trigger Warning website. Survivors of all ages and genders are welcome to participate.

“I always schedule two meetings with each survivor. First, we meet just to talk. I invite each person to share their story at their own level of comfort. I often ask questions along the way. We meet a second time to make photographs, always outside, and at a location where they feel safe. The photographic process never takes more than an hour, and we talk along the way. Though the portraits end up looking very formalized, our time together remains as casual and comfortable as possible.

“I’m sure each survivor experiences these meetings very differently. Some feel emotional and heavy-hearted, others express anger and frustration, a few have used humor to naturalize their experiences, and some feel numb. Several of the survivors I’ve photographed are very comfortable talking about their assault(s) and have spent many months and years dealing with their rape(s). The emotional and expressive spectrums are wide. Many individuals have told me that having an opportunity to share openly is an extremely rare experience, one that helps them to feel supported.”

Although prostitution is illegal in the United States, a middle-aged man struggling through his marriage hired an escort during a weekend away from home. They drove together to a motel and booked a room for a few hours. Through his own confusion and assumption, he forced his escort into sexual acts she was not comfortable with.

Although prostitution is illegal in the United States, a middle-aged man struggling through his marriage hired an escort during a weekend away from home. They drove together to a motel and booked a room for a few hours. Through his own confusion and assumption, he forced his escort into sexual acts she was not comfortable with.

A teenage girl, around 15, regularly spends time at her father’s auto shop. She helps with odds and ends, and works her way toward a full-time position. One afternoon, she is invited to share lunch behind the garage with one of the other employees. Partway into their meal, he propositions her for sex. When she refuses, he rapes her anyway.

A teenage girl, around 15, regularly spends time at her father’s auto shop. She helps with odds and ends, and works her way toward a full-time position. One afternoon, she is invited to share lunch behind the garage with one of the other employees. Partway into their meal, he propositions her for sex. When she refuses, he rapes her anyway.

How has the response been for the work thus far? Do you feel that people are grateful to have your series begin a dialogue?

“Almost everyone I’ve spoken with has responded positively to the work. While the impact that viewers feel is intense and striking, they often express that they’re grateful and eager to engage in the dialogue that the work provokes. Many understand the importance of talking about rape, but express that they have a hard time doing so. Some people view the work and simply move on without speaking to me. I sense that it takes each person a different amount of exposure and time to internalize and engage with the issues, which of course is perfectly healthy.

“I often receive emails and messages of thanks from friends, colleagues, and strangers. The most exciting responses for me are those, which express an eye-opening or enlightening experience. Fairly often, new viewers will learn or realize something about rape or survivor-hood that they’d never before been aware of or been able to understand. These moments of clarity and gratitude continually fuel the project and my individual motivation and creativity.”

Though seemingly the home of an accepting and open community, two members of the clergy in this church have been reported for sexual assault on young children. Parents of the children have pressed charges, and are waiting for court appearances scheduled within the month. Until a verdict is reached, the clergy continue their regular duties.

Though seemingly the home of an accepting and open community, two members of the clergy in this church have been reported for sexual assault on young children. Parents of the children have pressed charges, and are waiting for court appearances scheduled within the month. Until a verdict is reached, the clergy continue their regular duties.

Is the series a work in progress? Are you planning on continuing outside the Rochester area?

“Yes, Trigger Warning is coming up on its 3rd anniversary as an idea, so it’s quite a young project. Most of the photographs are a little over one year old and I’m continuing to make new portraits all the time. In the future, I plan to speak with and photograph perpetrators of rape. As it stands, rape education is extremely reactionary and is only preventative on the side of the victim. We need to be doing a better job at educating young men and women about respecting others’ bodies, not simply about protecting their own.

“I’m eager to hear perspectives of men and women who have perpetrated violence and been able to deconstruct those behaviors. Rapists and rape survivors are products of the same societies, educational systems, and cultures. I can’t fully represent the issue if I only approach it from one side. The project is only centralized in Rochester at this time because I happen to live there. I plan to carry Trigger Warning with me to every community I live and possibly travel. I imagine this to be (though I’m still young) my “life’s work” of sorts. This conversation will certainly not end in my lifetime, so neither will this work.”

Trigger Warning is a touching documentary as well as a bold venture into something generally not spoken of. What do you hope the work ultimately achieves and people take away from reading these stories?

“Ultimately, my goals are to impact my communities and networks quite directly and to also infect more broad-spread areas, groups, and culture with a positive, anti-rape perspective. I’m currently working with Rorie, who has become my creative partner, to begin speaking at colleges, organizations, community groups, etc. Our goal at its simplest level is to create safe spaces to talk about rape. We have both found in the years since her rape that everyone we talk to has either survived a rape, or knows someone who has.”

“Trigger Warning works to create a greater level of awareness and understanding of rape and its effects on individuals, communities, and society. I’m also actively pursuing partnerships with advocacy organizations, foundations, and non-profits which fight to end rape. I’m working to grow Trigger Warning’s network immensely, and hope that the photographs might ignite a desire in others to foster dialogue and anti-rape works in their own networks and worldwide.”

At a party during her sophomore year, a 20-year-old college student drinks to excess. After most of the guests leave, she agrees to sleep at the apartment of the host, who is a friend of hers. In the middle of the night, she wakes up to find a man she’s never met penetrating her. The man was also a guest at the party.

At a party during her sophomore year, a 20-year-old college student drinks to excess. After most of the guests leave, she agrees to sleep at the apartment of the host, who is a friend of hers. In the middle of the night, she wakes up to find a man she’s never met penetrating her. The man was also a guest at the party.

On the outer fringe of a large city stands this house, the home of a long-married couple, the parents of two who have outgrown their childhood home. As they grow older and the husband retires, he begins to feel weaker and less useful. In a misguided effort to regain the power he once felt, he continually rapes his wife of 35 years.

On the outer fringe of a large city stands this house, the home of a long-married couple, the parents of two who have outgrown their childhood home. As they grow older and the husband retires, he begins to feel weaker and less useful. In a misguided effort to regain the power he once felt, he continually rapes his wife of 35 years.

Each afternoon, a young boy waits for his father to pick him up from school. At the end of each week, the boy is treated to an ice cream cone. One Friday, when he is 12, the tradition is broken, and instead of buying ice cream, his father drives to the back of the entrance of the school and molests his son in the car.

Each afternoon, a young boy waits for his father to pick him up from school. At the end of each week, the boy is treated to an ice cream cone. One Friday, when he is 12, the tradition is broken, and instead of buying ice cream, his father drives to the back of the entrance of the school and molests his son in the car.

A 30-year-old bartender took her usual walking route home one late night after work. She had never experienced or heard of violence in the neighborhood, but crossed the street when she sensed someone following her. About two blocks later, the stranger had caught up and grabbed her by the wrist. She struggled, but he forced her into the driveway between these two homes. After raping her, he left her on the street. She stumbled the remaining half-block to her apartment and called the police.

A 30-year-old bartender took her usual walking route home one late night after work. She had never experienced or heard of violence in the neighborhood, but crossed the street when she sensed someone following her. About two blocks later, the stranger had caught up and grabbed her by the wrist. She struggled, but he forced her into the driveway between these two homes. After raping her, he left her on the street. She stumbled the remaining half-block to her apartment and called the police.

This post was contributed by photographer and Feature Shoot Editorial Assistant Jenna Garrett.