Search this site

Trash Organized Neatly: A Photographer’s Colorful Collection of Discarded Objects

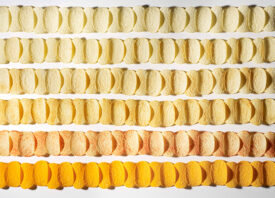

Living in the heart of any metropolis for a decade or longer might require periods of seeking alternate views, scents, and sounds, regardless of how ‘urban’ we consider ourselves. Native urbanites, too, need the sun and sea, sand, and wide-frame vistas. NYC-based photographer Barry Rosenthal‘s series Found in Nature speaks to an impeccably organized urbanite who, despite shooting objects that were found along the coastal areas of New York Harbor, still packed them tightly and densely into frame, much like all of us on the subway during peak commute hours, looking like quite the–ahem–can of sardines.

We asked him a couple more questions about his quest for these found objects and how it was he came to photograph them.

Do you have a method to this project?

“From collecting comes inspiration for new ideas and pieces. Collecting is the foundation of the project. I collect everything myself. I collect only from coastal areas that have an immediate connection to the ocean. Periodic collecting is a means of renewing the project. I seem to pick up energy from collecting to carry me further with my work.

“Collecting is the first step in a creative cycle. Finding a theme, sorting the objects, combining objects, building a composition, filling a space, and finding a lighting solution are steps I go through to make a piece. At some point in the building the composition or sculpture some intangible emotional feeling is imparted to piece. There is an intimacy between the objects and myself. Intimacy transforms into soul.”

What has finding these discarded elements of humanity taught you, or elicited in you as a person/father/husband/photographer?

“I have learned that plastic is forever. Breaking down plastic pollution into ever smaller bits is not a solution. Plastic must be removed from the environment and not allowed to cover the oceans and land. The oceans need advocates. I do a small part to further the visibility of ocean-borne pollution. Education is important in showing what is already in the environment. I’m an artist. I didn’t start out to make a political statement with my work. I was attracted to these ‘lost’ objects. The work continues to evolve. I want to make a statement about contemporary archeology. We are what we produce.”