Search this site

Gripping Portraits Give Voice to Afghanistan’s Imprisoned Women, Jailed for ‘Moral Crimes’

In Afghanistan, countless women are imprisoned for what are referred to as “moral crimes,” a vague term used to apply to cases in which they have fled from abusive and forced marriages or domestic slavery, and to accusations of premarital sex, very often applied to survivors of forced sex work and rape. While those who do violence to these women might walk free, their victims are deposited in one of the country’s prisons, sometimes pregnant with little hope of a future for themselves and their children.

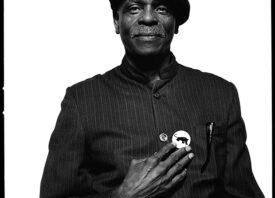

The Polish-Canadian photographer Gabriela Maj spent four years visiting women in their cells, where they live alongside five to ten fellow prisoners. Here, she sat with them, listened to their stories, and when she was permitted, took their portraits, collected in her new book Almond Garden, titled after the infamous women’s prison Badam Bagh.

Maj first visited an Afghan women’s prison in 2010 on an assignment; soon after, she felt herself unable to let go of the faces she had encountered and the stories she’d heard. She would spend the next few years tenaciously seeking access to other facilities, and although she was rejected time and again, she was allowed into several facilities, perhaps because her gender seemed to pose little threat to the authorities.

Often, she was left alone with the women and a single interpreter, at which point she simply took off her shoes and asked individuals or a group if they had anything to say. Sometimes, a nearby guard would scoff at her, expressing distain for the fact that she treated the women with care and dignity.

Maj was immediately struck by the eagerness of the women around her, and although only a select few were willing to be recorded, many were relieved at the chance to tell someone what had happened to them. These women had never been presented with someone who would listen, suggests Maj, and the prospect of sharing some of that burden—if only for a moment— was irresistible.

Still, the women were sometimes intimated by guards and feared that sharing their histories might put them in danger. Some opened up, while others quietly watched as the photographer worked, talking amongst themselves. Maj promised not to publish words or images for which she had not received the permission of her subject, and she kept that promise.

The jails, explains the photographer, do not have bars or uniforms, meaning that the women can to some degree personalize their spaces. Despite what they had endured, the woman continued to live their lives and to care for their children. One built her baby a cradle from a broomstick and pieces of fabric.

Although basic needs like meals and shelter were provided for the women, Maj reports that medical care varied from one facility to the next, and there was a conspicuous absence of mental health resources. The jailed women were vulnerable to sexual exploitation, and many faced the responsibility of bringing up their children from within the prison walls.

When the photographer asked the women about life after jail, many responded “I will be killed.” One of the most daunting aspects of being incarcerated is the fact that upon her release, a woman will find herself disowned by her family and with no place to call home.

Since the close of the project, Maj has tried to keep track of the women she met through aid workers who transport donated goods to the prisons, but once they are set free, they are difficult to find. Some find refuge in shelters or move to big cities, but Maj has been told that at least two have been murdered by family members in honor killings. In cases like these, the women— and often their children— are perceived as having brought “shame” to their households and communities. For the majority, a safe and fulfilling life after prison is unthinkable.

To help the imprisoned women of Afghanistan, Maj suggests supporting the ratification of Afghanistan’s Elimination of Violence Against Women (EVAW) laws and visiting Women for Afghan Women (WAW), an organization that maintains shelters, provides legal aid, and offers education for the children of imprisoned women. Learn more about Almond Garden here.

Gabriela Maj is a Polish-Canadian photojournalist whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Bloomberg News, Newsweek, Esquire magazine, Frontline and on CNN. Her first book, Almond Garden published by Daylight Books investigates women’s prisons in Afghanistan via photographs and interviews collected between 2010-2015 from over a hundred incarcerated women. The book is available at www.almondgarden.net with a portion of the proceeds to benefit Women for Afghan Women.

All images © Gabriela Maj