Search this site

Witty, Mysterious Photos Mix Fact and Fiction, Past and Present

Lying Still, Birthe Piontek’s series of found and staged self-portraits and set ups, quivers with an air of threat, transformation, and mystery. In the bright melancholy light of Piontek’s rooms, visual evidence accrues. Red string hangs on the wall in a pelvic triangle. A woman writhes in the sky. Dark berries obscure a woman’s mons pubis. Bedsheets hang from empty windows. A woman’s back is alarmingly bruised in the bold pattern of a Marimekko print. We feel a loud hush, something like the theatrical quiet before or after a crisis. Or maybe it’s the beat before a punch line.

The photographer uses herself as a model and her home in Vancouver, BC, as a set. (A few of the photos were taken while traveling in the Yukon and in the photographer’s native Germany.) Among the color set-ups and self-portraits, Piontek intersperses found black-and-white press photos from the fifties and sixties. They add a dose of nostalgia and, unexpectedly, foreboding.

Piontek built the series slowly. “I worked on Lying Still on and off for five years, carried it with me, let it simmer and gave it a lot of time,” she says. She spent much of the time researching the mid-century press images and planning her deceptively simple set-ups. This slow-cooked approach may help account for the resonances and connections among the images. A dreamy alchemy obtains. Objects seem to move and jump from one image to another. Time seems moves in a peculiar way, past and present intertwined.

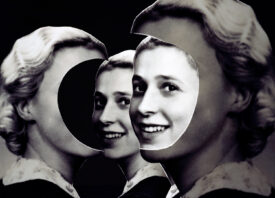

A sequence of three images illustrates. Piontek sits on the edge of a bathtub with a towel draped mysteriously over her head. Then we see an press shot of a glamour-puss in sunglasses, face half-veiled by a scrim of black scarf. Finally, there’s Piontek with her face submerged in a shallow bowl of water, her face strangely doubled.

The visual puns pile up. Towel over head equals veil. Veil divides face in two. Water, same. Face obscured in all. The art historical references do, too. Doubling of features: Picasso. Covering an object in fuzz: Meret Oppenheim (whose funny, unnerving fur-covered tea cup of 1936 is a key image in Surrealism and also in understanding Piontek’s set ups). Disguise and self-abnegation: Cindy Sherman. Glamorous suffering: Warhol’s Jackie O.

Finally, Woman’s bodily suffering. In this short sequence and throughout, Piontek obscures the face, which emphasizes the body and its scars and bruises. Feminist artists of the seventies like Hannah Wilke, Ana Mendieta, and Carolee Schneeman, whose work frequently deals with bodily depredations, come to mind.

So, just in the short sequence of three, we are left to wonder about two-facedness, public and private selves, fact and fiction, past and present, the special pain of women, and the representation of the body. Phew.

Against this dizzying background of multiple interpretations and allusions a couple of facts seem in order. One fact: the artist says that the awful bruises turn out to be the result of something called cupping, a suction technique used in acupuncture. Perhaps the point was healing not suffering. Another fact: the press photo of the woman in sunglasses is actually Marie MacDonald, a forties pinup star — complete with scandals, multiple marriages, and a final, lethal overdose. It turns out MacDonald’s nickname was The Body. An art historian couldn’t have hoped for a more apt fact. It’s Piontek’s ability to mix fact and fiction, past and present, black-and-white and color, jokes and dread that helps account for the strange mood in these plain rooms.

All images © Birthe Piontek