Search this site

Extraordinary New Book Unveils the Untold Stories of the World’s Greatest Photojournalists

Arlington, Virginia, 25 novembre 1963. © Elliot Erwitt / Magnum Photos

Afghanistan, 1992.© Abbas / Magnum Photos

The duty of a photojournalist, according to many, is to remain detached in a moment of crisis, to compartmentalize scenes of violence and war from the goings on of everyday life. As suggested by Italian journalist Mario Calabresi in his extraordinary book Eyes Wide Open, however, the best storytellers are those who allow themselves to be submerged within often painful events, to forgo absolute objectivity in favor of something rarer: a precarious marriage of impartiality and intimate involvement. In interviews with ten photographers who have not only documented but in many ways shaped the course of history—Steve McCurry, Josef Koudelka, Don McCullin, Elliott Erwitt, Paul Fusco, Alex Webb, Gabriele Basilico, Abbas, Paolo Pellegrin, and Sebastiao Salgado— Calabresi peels back the layers that lie behind iconic images to reveal the nuances of each frame and the living, breathing people who stood behind the lens.

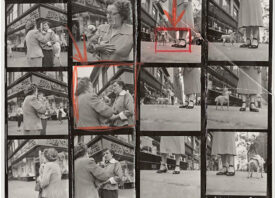

Calabresi met with each of the ten photojournalists over the course of the last five years; he sat down with them in person wherever he could and whenever they were available: in offices, studios, meeting rooms, and homes around the world. Over hours-long conversations, he listened to McCurry on monsoon season in India, McCullin on the blood-soaked Battle of Hue, Koudelka on the invasion of Prague, Salgado on Rwandan genocide, Erwitt on racial tensions from the 1950s up until this day, Fusco on the funeral train of Bobby Kennedy, Pellegrin on Iraq, Abbas on the Iranian Revolution, and Basilico on civil war in Lebanon and the abandoned ruins of Beirut.

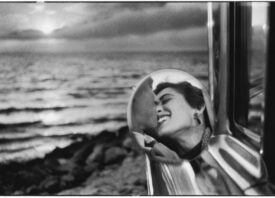

In every one of these legendary photojournalists, Calabresi finds warmth and passion, whether they’re speaking on their own homes or journeys overseas. These are people who are themselves players in each shot, not spectators waiting on the sidelines. He tells of McCurry diving into the flood waters that overtook the Indian village of Porbandar, where the photographer stood for entire days as dead animals drifted past and leeches feasted on his flesh. Pellegrin fled the custody of British patrolmen to shoot, unprotected, as Baghdad was taken; Erwitt got close enough to catch a falling tear stain the veil of Jackie Kennedy at the funeral of her husband. McCullin, instead of continuing to shoot, dropped his camera in Cyprus to save a toddler; in Vietnam, when a dying soldier indicated that he did not want his photograph taken, again the photojournalist lowered the camera.

Doing this work, and doing it fully, comes at a cost. Making images that shape nations, that spur change, and that remain imprinted in the minds of millions, can bring sleepless nights and moral crises. Salgado, after bearing witness to so much horror, felt his body and mind buckle under the burden; there is one photo, picturing a starving albino boy in Nigeria during Biafra war, that still haunts McCullin. Because of his photographs, Koudelka spent two decades in exile, missing the death of his parents. Despite all the sacrifices, the death, the shock, and the grief, Eyes Wide Open emerges as a life-affirming ode to these men and to their spirits.

Calabresi’s testimony is one colored by honesty and true affection, a story told by an author who lent an open ear and invited each photojournalist to talk him through his memories. His directness, as it turns out, even warmed the chilly and difficult exterior that Erwitt is famous for exhibiting during interviews. These men, too, have come out the other side of war and conflict; they still might bear some wounds, but they have at long last found hope.

For McCullin, finding joy can be as simple as watching the deer emerge from the early morning mist along the the Somerset countryside; for Pellegrin, it’s his daughter Luna, and for Salgado, it’s the planet and all its remaining natural wonders. He’s healed, he says, from rebuilding the Brazilian rainforest surrounding his boyhood home. And finally, for Basilico, who has sadly passed away since his interview with Calabresi and for whom the author gives a special thanks in the closing words of the book, it was longing to do it all over again, to start once more with photographing the ports of cities around the world and perhaps, despite it all, to move on one last time to all that came after.

Eyes Wide Open is published by Contrasto as part of a collection called In words that examines the relationship between text and images.

Beirut 1991. © Gabriele Basilico

Beirut 1991. © Gabriele Basilico