Search this site

Powerful Photos Document the Iranian People Derailed by the Current Water Crisis

In Siasar village, to go to toilets, people have to go away 500 meters from the village to avoid the flies that are attracted by human feces and make people crazy.

Some days, milk is lacking, so people first feed the animals and then drink the remaining milk.

“Iran is becoming an uninhabitable desert, and do not think it will happen in the future — it is happening already.” – Isa Kalantari, former agricultural minister of Iran.

Iranian photographer Mahdi Barchain’s latest series, Living with Dry Hope, confronts Iran’s current water crisis by telling the story of the last survivors at Hamoon Lake. These are the fisherman, the mat weavers, and the farmers who have known no other way of life, and for thousands of years have followed in the footsteps of earlier generations. Now, these people face a critical situation: Hamoon Lake, located in south-eastern Iran close to the Afghanistan border, is just one of many lakes in the country that is vanishing at a rapid rate. In fact, almost no water remains at all. This is the result of a number of both human-induced and environmental factors, but mainly due to poor water management and the fact that Afghanistan refuses to let water from its rivers drain into Hamoon.

In a succession of trips to semi-abandoned villages over period of nearly two years, Barchain braved the 120-day storms, formed contacts within the places she visited and photographed exactly what she found there. Among the many things she saw were people spiraling into opium addiction, ghost towns full of the relics of fishing boats and derelict houses, and people too poor to buy themselves shoes or blankets to keep warm at night. The sole hope remains on everyone’s minds: ‘they only pray for the return of the water in the lake’.

For the survivors, the situation is bleak. Many don’t own identity cards because of their limbo-existence between Iran and Afghanistan, which means they cannot relocate to other Iranian towns because of their refugee status. Barchain adds that, “more than 600,000 children live in Iran without identity”.

What once was the country’s third largest lake (3820 square kilometres), and formerly a valuable life source to its inhabitants, is now a ghost town. Because there remains little hope to revive the Hamoon Lake, Barchain’s elegiac photographs reveal a landscape and community in turmoil; the people struggling against the elements to survive because they have nowhere else to go. Her series also reflects the wider drought issue that expands way beyond Iran’s borders and encompasses most of the Middle East, and through these powerfully honest images, we are forced to confront the stark reality of the situation as it stands today.

400,000 people live around Hamoon, a dry lake on the Iranian shore. In summer the temperature may exceed 50 degrees C. There was a big lake before fed by the Helmand River.

The lake is dry because Iran and Afghanistan governments have a conflict about the Helmand River.

As the lake is dry, the fishermen’s boats have been turned into water tanks.

Many families have more than 5 children each. Now that the lake is dry, people are poor and cannot send the kids to school. Their future will be to leave the place where they lived for centuries and to find job in another city where they are not welcomed.

Many men are desperate and fall into drugs like opium. They can easily access it, as they live near the Afghani border. Some fear the kids will become addicts, as the smokers don’t hide the habit.

The sand storms create lots of eye problems, and people are too poor to go to hospital, so they try their best to cure by themselves with simple items.

Getting access to a doctor is a real problem in Siasar village as the network doesn’t work most of the time.

“I’m shepherd in Moladadi village. The farmer’s work has changed the soil, so when the wind is blowing, it creates sand storms.”

Women have to walk 4 Km to find some wood for make fire for bread. There is less and less wood is this sandy area.

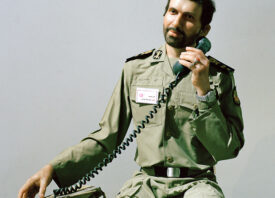

The lake is also inhabited by nomads like this man who comes from Baluchistan. They were rich before because they could feed their huge flocks of sheep, but now they can’t find any grass to feed the cattle.

Mohammad is 6. He lives in Siasar village and can’t go to school as the area is far from the first school, and his father asks him to guide the cows to try to find grass along the lake.

All images © Mahdi Barchain