Search this site

The Stunning Araki Retrospective at the Musee Guimet (NSFW)

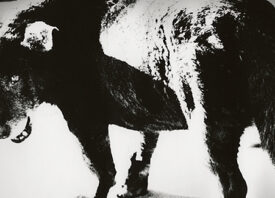

Nobuyoshi Araki is one of the most prolific artists worldwide, having published over 350 photobooks in Japan and internationally. For the Japanese artist, “photography is, above all, a way to exist”, and this is evidenced in his work; equal attention is given to a nondescript street scene as to a rope-bound woman. To view his photographs is to feel oneself immersed in his world, one which is by turns hilarious, banal, disturbing and tender.

The retrospective of his work shown recently at the Musée Guimet in Paris, displaying over 400 of his photographs, was a major exploration of the phases of his production, ranging from his earliest work – Theatre of Love, 1965 – to his latest, Tokyo Tomb, produced for the museum in 2015.

The opening of the exhibition is a striking cornucopia of visuals and emotions. The first room, quiet, displays large prints of fat, dripping flowers as recorded by Araki in vibrant colour, and his themes are neatly introduced: beauty, putrescence, eroticism. That room gives way to two of his most powerful photographic narratives, ‘Sentimental Journey’ and ‘Winter Journey’, focussing on his honeymoon and the death of his wife respectively. While later work is vivid and bombastic, this more domestic portrayal is quieter, Araki’s touch lighter. His wife, Yoko, sits glowering in a hotel room bed; later, her head is thrown back in sexual ecstasy or pain. In the latter series, we mainly follow Araki’s cat as it stalks, unsuspecting, through suburban Tokyo, before suddenly a hospital scene looms; then, breathtakingly soon afterwards, we see Yoko, gorgeous, in her coffin, her face framed by flowers and the hands placing them. The way that Araki layers moments to create the narrative of, first, his love for his wife, then her death, is remarkable.

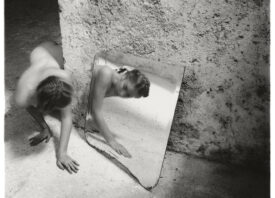

In the next room are large diptychs of Araki’s work about Kinbaku, or traditional Japanese rope bondage. Images of women bound by ropes are placed next to cherry blossom, a street scene, a fish; the juxtaposition desexualising the rope images, instead suggesting their sculptural quality, their delicacy and the beauty of the human figure. The women in the photographs seem unperturbed; their quality is static, notions of form rather than sexual power or dominance. Araki’s playful tendencies are ever in evidence, for example in an otherwise highly charged rope scene where a toy stegosaurus sits quietly in the foreground (dinosaurs and other toys are a frequent occurrence in Araki’s work; often his most serious-feeling images are tempered by their presence, a nod to a sense of humour even in his most high-flown artistry).

As the exhibition progresses it becomes more frenetic: we are given an increasing sense of Araki’s prolificness, his camera standing as the permanent observer in his unusual life. Women and sex are obviously fixed themes, and many small black and white photographs centre on their forms twisting across motel room beds; so too is the city, with images of the street and its detritus constellating across his diaristic work.

Though he favours off-kilter black and white 35mm imagery, Araki is plainly unafraid of experimentation. The exhibition showcases photographs he has painted calligraphy onto, and ones hand coloured with bold and irreverent strokes of paint. A tender moment comes in ‘Skies’, a collection of photographs of the sky which Araki has apparently photographed every day since his wife’s death. Finally, Tokyo Tomb, a collection of photographs that Araki has compiled from the full reach of his portfolio (how long it must take him to find the right negatives – or what his filing system must consist of – is a dizzying thought!)

Araki is impressive, if nothing else, for the breadth of his attention. His work is delicate at the same time as it is plainly aggressive, exploitative; he is just as somber as he is playful. In his writing about Tokyo Tomb, Araki himself iterates his tendency to compile and combine contradictory elements: “if Heaven does not include the elements of Hell, it is not Heaven.” The Musee Guimet have put together a show which does superb justice to his expansive output.

All images (C) Nobuyoshi Araki, courtesy of the Musée Guimet.