Search this site

One Photographer’s Journey to 12 Nazi Concentration Camps

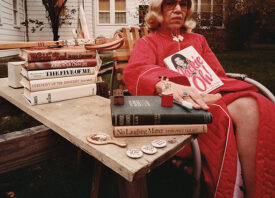

Survivor of three Nazi concentration camps, survivors’ reunion, Majdanek concentration camp, near Lublin, Poland, 1983. being honored by Poland as a heroine during a nationally televised event. She wore her uniform with her prisoner number and a red triangle with a “P,” indicating she was a Polish political enemy of the Third Reich. The onlookers in this photograph seemed more interested in my large, unusual camera, tripod and dark cloth and my odd photographic machinations than in her. © James Friedman

Wall where Jewish prisoners were shot, Theresienstadt concentration camp, near Terezin, Czechoslovakia, 1981. I set up my camera in front of this wall and its forty-year-old bullet holes. I saw an East German man and his son nearby and immediately decided to include the boy in the photograph because the color of his sweater nearly matched that of the number “37” on the wall. Though I didn’t speak German, somehow I was able to gain the father’s permission to photograph his son. © James Friedman

When James Friedman presented his photographs of Nazi concentration camps at the International Center of Photography in the mid-1980s, a fierce argument ensued between two members of the audience. One was outraged at his choice to capture the camps in color; the other defended it. There was shouting; people got up from their chairs before the fight was put to rest.

Friedman vividly remembers the words that sparked the debate. They were directed at him: “You can’t photograph Nazi concentration camps in color, on sunny days. What’s wrong with you? How could you take pictures like that?”

Historical black and white of pictures, taken during the rescue of Holocaust survivors, are harrowing, but the lack of color serves as a reminder of the passage of time. Black and white allows us to distance ourselves—at least in some sense—from both the victims and the perpetrators of the genocide.

During the argument at ICP, the same man told Friedman, “There weren’t any deep blue skies or puffy white clouds during the Holocaust.” Of course, we know there were. It was a sight that would haunt photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White from the day she set foot at Buchenwald in 1945 until her death in the early 1970s. In her memoir, Dear Fatherland, Rest Quietly, she would write about “the bright April sun” and “a clean blue sky” that hung over what she could only describe as “indescribably horrible.”

The color of Friedman’s photographs is what makes them remarkable. He traveled to the sites of twelve concentration camps in 1981 and 1983, carrying his large 8×10 camera. He includes pieces of himself in many of the images: his handwriting, his possessions, his fingers. They are pictures about the Holocaust after the Holocaust ended.

He got to know these places well; for one photograph, he lay down on his belly and contorted his body. In others, he was afraid and needed to anchor himself in the present day. In tourist sites and reclaimed land, the memory of all that happened remained.

When I was in elementary school, my class was shown a slideshow of some of the most well-recognized and painful images from the Nazi concentration camps. Before the black and white images rolled onto the screen, my teacher warned us they would be very upsetting—we were allowed to leave and stand outside until it was over. I was a little girl, and I am Jewish. Scared of what I might see, I left the room until the teacher told me it was “safe to come back in.”

Friedman’s photographs are a reminder of the terrible fact that in many ways, it will never be “safe to come back in.” These places don’t exist in black and white; they live in color, alongside the rest of the world, out in the open.

12 Nazi Concentration Camps opens October 13th at the Cincinnati Skirball Museum. The exhibition is presented in partnership with The Center For Holocaust & Humanity Education and FotoFocus and the 2016 Biennial.

Local resident with scythe and self-portrait, Auschwitz ll (Birkenau) concentration camp, Oswiecim, Poland, 1983. Since the end of World War ll, local residents of Oswiciem, Poland had been assigned small plots of the 17 square-mile former Auschwitz-Birkenau Nazi concentration camp site to tend and maintain. During my photographing there, this man was using a scythe to cut the grass on his plot. Through an interpreter, he told me he had helped prisoners escape from the camp during the war. © James Friedman

Polish soldiers at entrance to Auschwitz l concentration camp, Oswiecim, Poland, 1983. The soldiers had been assigned to Auschwitz-Birkenau as part of their tours of duty. Standing under the entrance to Auschwitz l that displays the German slogan, “Arbeit Macht Frei,” (translates as “work sets you free”) they were delivering picture frames to one of the camp’s exhibits. © James Friedman

German family, Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, near Hannover, Germany, 1981. As I made this photograph on a rainy Sunday afternoon, I thought of August Sander’s pictures of Germans from his series, “Citizens of the Twentieth Century,” and how this family looked as if they had stepped out of one of Sander’s photographs from the 1930s. I sensed the ghosts of Margaret Bourke-White and George Rodger lurking nearby; their photographs (including ones at Bergen-Belsen) revealed the death camps in the May 7, 1945 issue of Life Magazine. © James Friedman

Parking lot, Dachau concentration camp, near Munich, Germany, 1981. I made this photograph on the second day at Dachau. Adjacent to the camp was a parking lot that was situated between a restaurant and a soccer field. From the restaurant I saw a boy playing with a remote-control toy car in the empty parking lot. Rather than use the tripod with my 8” x 10” folding field camera as I typically did, I composed the photograph by lying on my stomach and positioning the camera on the gravel surface until everything looked coherent and I made the picture. © James Friedman

Sculpture and photographer’s amulet, Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp, near Strasbourg, France, 1981. By the time I photographed Natzweiler-Struthof, I was overwhelmed by the persistent feeling of evil that inhabited each camp; this was a sensation I was unable to escape. When I saw this horrific sculpture at the entrance to the camp, instinctively I reached into my pocket for the amulet I carried with me for protection during the entire trip. The amulet is a miniature, plastic muscle man that is part of a set of toy circus figurines I have had for more than three decades. © James Friedman

Survivors’ reunion, members of the Dutch resistance, Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp, near Strasbourg, France, 1981. The survivors of Natzweiler-Struthof, now living throughout the world, told me they returned to the camp frequently for reunions. When I asked if Jews had been imprisoned there, they said yes and told me they did not know why there was no mention at the site that Jews had been murdered there. © James Friedman

Pool into which ashes from crematoria lV and V were dumped, Auschwitz ll (Birkenau) concentration camp, Oswiecim, Poland, 1983. This serene, seemingly idyllic spot of respite was within walking distance of the crematoria. Some years later, I read that the author of a New Yorker magazine article about Auschwitz-Birkenau had dipped his hand into this pond in the early 1990s and found bone fragments from Auschwitz ll’s crematoria. © James Friedman

Delivery truck, Russian monument, entrance to Mauthausen concentration camp, near Linz, Austria, 1981. The truck delivered items to the café at Mauthausen. I was grateful to have been able to photograph in Austria, after machine-gun-wielding Czech soldiers threatened to destroy my equipment and film at the border crossing from Czechoslovakia into Austria. Only after they brandished their weapons did I remember to show them the document I had requested from the Embassy of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic that identified me as an American professor authorized to photograph in their country. © James Friedman

Marker indicating execution range with blood ditch, Dachau concentration camp, near Munich, Germany, 1981. I walked on a gravel path leading away from the crematorium at Dachau and saw an engraved stone, decorated with glorious flowers that read, “Execution range with blood ditch.” I added my orange architect’s triangle I had brought with me as a way to connect me to the safety of home. © James Friedman

Restaurant, Fort Breendonck concentration camp, near Brussels, Belgium, 1981. Near the entrance to Fort Breendonck was a restaurant whose terrace and diners were bathed in the beautiful light of late summer. The juxtaposition of the restaurant and the grisly fortress inspired the photograph. © James Friedman

Site where prisoners were shot en masse, Flossenbürg concentration camp, near Bayreuth, Germany, 1981. My photographs of the camps represent a sort of visual diary, and in some of the images I included notations or commentary. © James Friedman

Survivors’ reunion, Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp, near Strasbourg, France, 1981. I asked the group of survivors and their families to pose behind the barbed wire fence. I was inside the camp as they were meeting outside in a rest area. Before the trip, I had thought about whether or not to include in the photographs the most overused symbols of the Holocaust, such as barbed wire. But, after seeing the camps, it was impossible to ignore them. © James Friedman