Search this site

Portraits Depict Life In A Powerful New Zealand Gang

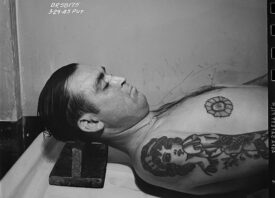

Casey Morton, a photographer based in New South Wales, Australia, wanted to document the contradictory existence of belonging to one of New Zealand’s most powerful gangs, the Black Power NZ. Formed in New Zealand by Maori and Polynesian men as a response to feeling marginalized in a colonized nation, they’re tough, live by their own creed, and are extremely exclusive.

And Morton, a Maori himself, wanted to gain access to them, if just for a day, so he could “tell the story of a group of people who are polarizing in the New Zealand community,” he told Feature Shoot. “To gain access to this group, experience a day with them, and to allow people to see a side of the gang that they may never experience.”

He didn’t want to merely paint the gang members in a positive light. “This shoot was never meant to persuade individuals that the gang are wholesome members of society. In fact, I really just want individuals to see the images and make their own mind up,” he said, adding that gangs are a fact of life for anyone who lives in New Zealand (for example, a picture of Black Power NZ members photobombing a couple’s wedding portrait went viral last year).

“I want people not to judge them for who they are, but to ask why gangs are so large in New Zealand, and why individuals choose this fraternity,” Morton said.

Morton was able to spend a day in a half with members of a chapter in Christchurch — access granted through two of his cousins who are members (“Without this, I doubt I would be able to do this,” he said). It wasn’t much time, but it was enough for Morton to ride with them through Christchurch, eat at a Denny’s, and capture candid moments, as well as make portraits of them in a makeshift studio set up in a clubhouse.

Using a Nikon D810, Morton said he gave them very little instruction, instead encouraging them to pose how they wanted in order to “ensure that the portraits were raw, natural and told the true story of each unique face.”

In the portraits, members show their patched vests proudly — like the Hell’s Angels in the US, the vests act like business cards, showing the members’ status — in order to earn a patch, members must go through a terrible initiation period that can last a year (for example, in a rival gang named Mongrel Mob, members are forced to “drink excrement and urine from a gumboot, rape someone, or fight three guys at once for a minute and survive on your feet,” according to a memoir by former Mobster Tuhoe “Bruno” Isaac.)

The raised fist, while borrowed from the Black Panther movement in the US, has less to do with anything political than it does with looking “cool,” says Jerrod Gilbert, a New Zealand gang historian. “The reason they’re called Black Power is it sounded cool and the reason they chose [the fist] is because it looked cool. I don’t think there is too much more to it than that,” he told New Zealand’s Sunday Star Times.

As a result of this project, Morton said his views of gang life have become more enlightened. “Hanging out with the gang was an interesting and quite confronting experience. I had my preconceived ideas (and concerns) about what it would be like to hang with a notorious gang, and whilst some of these ideas were true, many of my concerns were proven to be wrong. The gang were extremely generous of their time with me… At times I felt like I was just hanging out with family, uncles and brothers, but at the same time you also knew and could feel that there was a dark side to them.”