Search this site

Remembering the Horrific Exile of Thousands of People

Fatima Uzhakhova, Ingush, was a granddaughter of biggest landlord in the Caucasus. Her family was split: some were repressed as “public enemies” of the Soviets, andothers joined the Bolsheviks. In 1944, the family was exiled to Kazakhstan with thousands of others. In exile, Fatima’s mother was sentenced to five years of jail for breaking a rule: she crossed the frontier of her exile zone. Fatima had to survive on her own since the age of 9.

Chechen elders pose by the ancestry towers, which were ruined by the Soviets, rebuilt, then ruined again by the Russian army, and rebuilt again.

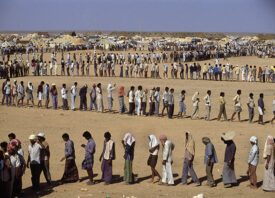

73 years ago today, the lives of nearly half a milion Chechen and Ingush people changed forever when Stalin ordered their deportation to remote parts of the Soviet Union. More than a third never returned, and the lives of the ones who did were already altered irreversibly. Russian photographer Dmitri Beliakov has been working in the North Caucasus since 1994 and came to learn about this dark chapter of history. As the witnesses of the exile were one by one disappearing, Beliakov felt time was slipping away. His project The Ordeal is the last chance to preserve their memory.

No Russian leader ever appologized for what happened, though the only reason for the hell these people went through was Stalin’s paranoia. The Chechens had a history of resisting authority, and they were suspected of collaborating with German forces as they entered the Caucasus between 1942 and 1943.

In the blink of an eye, entire families were loaded into cattle trucks and sent on 15-day journeys to Kazahstan and other remote parts of the USSR. The weakest, including many children, never made it to the destination. Those who did were strictly supervised and forced to report on other exiles, lest they risk lenghty sentences in the gulag. Only after thirteen years were they allowed to return to their homes.

For this project, Beliakov worked with known Chechen human rights activist Taissa Isayeva, who has relocated to Europe for her own safety. They tracked down survivors of the exile, interviewed them, and took their portraits. “I forgave Stalin,” one of the interviewees said, “Remembering was painful and emotional, and also necessary, as the project is a powerful documentation of a terrible moment in history that otherwise might have remained unknown.”

Abu Akhiadov, 112 years old, Chechnya: “We are nation of survivors. This is what we know. I survived WW II, exile, coming back and fighting for our homes upon arrival, the 1st and 2nd Russian-Chechen wars. I’ve no regrets. Allah gave me long life and many children from three of my wives. There is one thing I miss: a long time ago, the government awarded me with a remarkable medal for 100 years of hard work, and Russian soldiers stole it in the course of a mopping up operation in our village. They took it as a souvenir, but I need it back.”

Aina Akujeva, Chechen, photographed in the Grozny center for temporarily displaced people. She lost everything throughout the course of two Chechen wars.

Alaudin Shadiyev, Ingush, could be called “An Ingush Schindler” for his heroic activity at the time of exile. Mr. Shadiyev was a NKVD officer, and for this reason, he was not subjected to the repressions. Secretly, he tracked down his land mates in labor camps and improved their living conditions and saved lives in dodgy circumstances.

Amin Dovtukayev, Chechnya: “When I came home, my family had to fight for our land with people who lived there. We had to pay. When we obtained it, I found a burial ground, where remains of my grandfather were. hH must have been shot and burnt. Too many disabled people have been killed by the NKVD because they were unable to travel.”

Baudi Dzhantayev, Chechnya: “I was exiled, and then I spent 8 years in a labor camp for a crime. I stole food because I was hungry.”

Mukhtar Yevloyev, Ingush, poses with his sheep: “In exile, I had to start working at the age of seven as a shepherd.”

Hussein Esmurziyev, Ingush, was a WWII soldier and fought nazis on the frontline. He was called off from the front and exiled with his family to Central Asia.

Issa Khashiyev, Ingush, poses with Koran and two old daggers, one belonging to his father and the other to his grandfather. All artifacts were hidden from the Soviets in mattresses through the course of the exile.

Mukharbek Khashagulgov, Ingush, was also a WWII soldier who was called off the front and exiled with his family. His son made an outstanding career with the Soviet army and became one of only three ethnic Ingush Soviet generals with the air force.

Ozdoyev Makasharip, Ingush, poses with his WWII awards: “I would have been exiled with the thousands of others, but I was dedicated to continuing to fight, and my commander respected my honest service. We agreed that I would have a new name and a new Red Army fighter’s ID. I was made “Georgian” not Ingush, and I changed my surname. Because of this, I could continue to fight, and I took Berlin.”

Tovsari Chakhkiyeva, Ingush, 101 years old, poses at the ruin of her ancestry tower, which was built by her great grandfather. Mrs. Chakhkiyeva was exiled and came back to live on her ancestors’ land after the exile ended.

Sanu Mamoyeva, Chechen, poses with a suitcase that she made with her own hands in prison: “When exiled, I was sentenced to eight years in the labor camps “for anti-Soviet propaganda.” We were at a party for youngsters, where girls could socialise with young men, and we sang folk songs. One of these songs was mocking Stalin. An NKVD informant reported on this, and five men were arrested (including me). This broke my life: no one would marry me, and I only managed to marry after I was released from a labor camp. I was rehabilitated fifteen years later and was given certificate of rehabilitation, but no one ever would apologize. I would forgive them, but they do not come with apologies. That probably means they still think I am guilty. But I don’t know – what was my guilt?”

A certificate of rehabilitation for an innocent man who was killed. Dzhabrail Medov, an ordinary peasant, was executed in 1937 as a “public enemy.” His son was handed this certificate for full and complete rehabilitation of his father in 1956.

All images © Dmitri Beliakov