Search this site

The Bloody History of Colonization in Tasmania, in Photos

Eliza Pross is a descendant of Truganini who is famed as being one of the last full blooded Tasmanian Aboriginals. Eliza’s family is from Bruny Island, the home of Truganini.

Risdon Cove Massacre, 1804. Facts about deaths at this site are highly debated. One group claim that less than three Aboriginal people were killed during the conflict, while the majority of historians claim that over 30 Aboriginals were slaughtered. Image is overlaid with a John Glover painting.

When the Australian photographer Aletheia Casey was a child, she didn’t learn about any of the frontier conflicts of the time of colonization in Australia, and she didn’t learn about The Black War in Tasmania. Only years later would she discover the painful truth: during colonization, there was widespread violence throughout the country. Many consider what happened to have been a genocide.

The numbers are still contested, but some say that from 1804-1831, more than a thousand people were killed—over 800 Aboriginal people and 201 settlers. Soldiers and settlers from Britain kidnapped, raped, and killed Aboriginal people in massacres throughout the island. By 1835, only about 200 Aboriginal people remained, and they were forced to leave the land that was rightfully theirs.

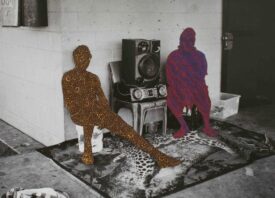

No Blood Stained the Wattle is Casey’s retelling of the often distorted history she was taught as a child. She photographed descendants of Aboriginal people from Tasmania and paired their portraits with landscapes captured in places of significance throughout Tasmania, including the sites of massacres. Then, she altered her large format film by painting over it and scratching its surface. If history can be revised, erased, corrected, and tainted, so too can photographs.

Casey’s version of the the story is truthful, but it isn’t linear. The secrets of centuries past are resurrected in the present. Forgotten places are rediscovered. Old wounds are opened once more. The experience of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people- their grief and their courage- didn’t end in the 1830s; it continues through today and into the future. We asked the photographer to tell us more about her process and the people she met along the way.

Christine Walsh’s great grandmother was an Aboriginal woman from mainland Tasmania however all birth records were burned in a fire. Christine’s Aboriginal ancestry traces back to Fanny Cochrane Smith who was the last full blooded Tasmanian Aboriginal woman.

How did you find out about the Black War?

“I started to become deeply interested in the history of Australia after I had lived abroad for five years and then moved back to Australia. I was shocked that Australia had seemingly created a history that began at the time of Captain Cook’s first arrival in Australia in 1770 and ignored the history of its original inhabitants. The narrative largely ignored the frontier conflicts and horrific violence that occurred throughout the country during the time of colonization and settlement.

“I read many different books by various historians in order to find out more about the Black War. Many aspects about how the war came about were horrific and shocking, such as the stealing of Aboriginal women by sealers and early settlers, which many historians argue was the real catalyst for the war.”

Matt Pross’s bloodline can be traced back to both Truganini from Bruny island, and Fanny Cochrane Smith, both considered to be two of the last full blooded Tasmanian Aboriginals.

How did you find your sitters?

“I knew the protagonist of the story, Eliza, from another series I did, After the Apology. Eliza was fundamental in educating me about Aboriginal customs and history. Eliza is a wonderful, positive presence, and she was hugely influential in making me ask the questions: ‘How can this series contribute positively to the situation in Australia, and how can we move forward together as a society?’

“The decision to add portraits to this series was a way of showing the strength and resilience of the Indigenous population and of showing that despite the horrors of what had occurred, there are still Indigenous Tasmanians who have bloodlines flowing back to Trugannini (famous for being a freedom fighter for Indigenous rights) and beyond. These bloodlines are proud, strong and resilient.

“The portraits and stories of Eliza Pross and her family comment on the unalterable trajectory of bloodlines and how this direct sequence of ethnicity influences and contributes to who we are as a people. The portraits are aimed at revealing a presence behind the appearance: communicating the historical presence of past ancestors and the hidden mysteries of history. They aim to make us reflect on the mythological understanding of ‘The Last Aborigine’ and are a testament to the hypocrisy of Darwinism and its theories. They share a direct dialogue with the landscapes they are paired with. They communicate that attachment to place is present, continuous and constant.”

Sally Peak, 1823. Aboriginal men kill two stock- keepers in reprisal for the abduction and rape of Aboriginal women. Stock-keepers attack and kill an unknown number of Aboriginal men in retaliation.

How did you find the massacre sites? What was it like physically being in these places?

“Tragically, there are actually massacre sites throughout Australia that are barely recognized, and so these that I visited are only a small example of the violence which occurred throughout the country. Out of all of the sites I visited, there is only one that is now fully governed by the traditional Indigenous owners. I used the writings of historian Lyndall Ryan and other Tasmanian historians to locate the sites and then used this research as a basis for the work.

“Tasmania is an incredibly stunning place. It is physically beautiful, savage, and wild. For me, this untamed wildness is both beautiful and quietly threatening. Because of the vastness of space and the lack of human presence, there is a distinct feeling of loneliness and unease- that despite the beauty and wonder of nature, there remains a sense of foreboding. Knowing what occurred in these spaces leaves a feeling of quiet dread, and a knowledge of the darker side of human nature.”

David Pross is Eliza Pross’s cousin and is from the same bloodline as Truganini who is famed as being one of the last full blooded Tasmanian Aboriginals. David’s mother was Dutch and his father was an Indigenous Tasmanian.

What is the single most powerful memory you have from your time making these images?

“Making portraits for this series was an incredible experience and also a privilege. All of the participants were unique and inspiring people, and each experience was different. I can ‘feel’ when a portrait is going to work, and this is how I felt particularly when I photographed both David and Eliza. David had a certain presence about him, a confidence and strength of character, which I feel really shows through in his portrait.

“I photographed Eliza several times. The first time it was storming, and the rain made it impossible to use my large format camera. The second time was surreal; the light was perfect. Eliza had brought a family heirloom of beads and also used traditional ochre to paint her face. I took several rolls of film this time and felt that there was an otherworldliness about the portrait I choose. The image gave me the idea to start painting the landscapes with the same ochre and then to scratch through them with beads, shells and features found in Tasmania in order to depict the uncovering of history through the imagery.”

Liffey Falls massacre site overlaid with a John Glover Painting.

You overlaid some of these photographs with John Glover paintings. Why?

“After I had photographed the landscapes of the massacre sites, I felt dissatisfied with the results. They were pretty landscapes, but they conveyed nothing of the horror the landscape had bore witness to. I decided that I needed a more emotional way of communicating aspects of the atrocity of our history.

“I started to research paintings and photography from the time of early settlement in Australia and came across the paintings of John Glover, who was a well known Landscape Painter. He depicted quiet, peaceful, and idyllic scenes, and he asked Indigenous Australians to dance and host celebrations so that he could capture these scenes.

“This depiction of Australia at that time couldn’t have been further from the actual truth of what was happening. There was a war brewing at the time; people were dying, and there were many incidents of horrific violence in the same areas he depicted. I decided to incorporate aspects of these paintings to show the hypocrisy of our history. We as a nation have created a fictitious narrative of our own history, both through literature and visual representations, that bears very little resemblance to the actual facts.”

Settled Districts, Hobart area, 1828: Martial law is declared against Aboriginal clans in the Settled Districts around Hobart, and Indigenous Tasmanians are now considered ‘Open enemies of the King.’

Cate Pross’s bloodline can be traced back to both Truganini from Bruny island, and Fanny Cochrane Smith, both considered to be two of the last full blooded Tasmanian Aboriginals.

North of Hobart. Site of The Black Line, 1830: As a result of the on-going conflicts between New Settlers and Indigenous Tasmanians Governor Aurthur called for every British man to form a human chain to capture and kill Aboriginal clans. ‘The Black Line’ was the largest force ever assembled against Aboriginal people anywhere in Australia. Those captured were forcibly removed to a remote island around 200km from the Tasmanian mainland called Flinders Island, where many later died from influenza.

Was this project emotionally taxing? If so, what motivated you to continue?

“I would say this project was intense, and it was also devastating in many ways to learn about the ‘other side of history,’ which has been mostly ignored.The motivation to continue the project was there from the beginning and intensified as I worked my way through the project. If I too didn’t tell the truth of our history, then when would the discourse in Australia ever open up to include the voices of those who have been silenced throughout history?

“A desire to recognize what has happened in the history of the country I call home (and which I feel a deep attachment to), along with the need of acknowledging the trauma and violence of the past, was a powerful motivation. As an Australian, I feel the burden of our stained history, and I feel the need of participating in the process of reconciliation. We need to be honest about our past and recognize the atrocious wrongs that were inflicted in order to move forward to a more positive future.

“As John Berger writes in his book Portraits, ‘A sense of belonging to the what-has-been and to the yet-to-come is what distinguishes man from other animals. Yet to face History is to face the tragic. Which is why many prefer to look away. To decide to engage oneself in History requires, even when the decision is a desperate one, hope.’”

Peter Shine’s bloodline can be traced back to one of the last full blooded Tasmanian Aboriginals: Truganini.

Bruny Island, Tasmania. The original home of Truganini, one of the last full blooded Tasmanian Aboriginals. Truganini witnessed her mother being killed by whalers. Her fiance was also killed while saving her from abduction, and in 1828, her two sisters abducted and sold as slaves. She was consequently a freedom fighter for the rights of Aboriginal people.

All images © Aletheia Casey