Search this site

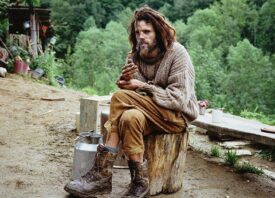

Photos of a Strange and Beautiful Australian Mining Town

In 2008, French photographer Antoine Bruy spent a year in Australia. When he returned home, he planned to bring with him more than a hundred rolls of film. All of them were lost. “Since then, I kept thinking of going back, to do something about this place,” the artist says.

The White Man’s Hole, the second chapter in a larger body of work entitled Outback Mythologies, took Bruy to Coober Pedy, an opal mining town that the novelist DBC Pierre once described as the “real Australia.”

The story of Coober Pedy began in 1915 with a 14-year-old boy named William Hutchinson. As Bruy tells it, William’s father Jim, a gold prospector, left his son behind one day at the camp, and the child set off on his own to find some water. When he returned, he had found water, and he had also found opal.

Miners flocked to Coober Pedy in search of prosperous lives. Thanks to the gem, the town flourished through the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. The town’s name comes from the indigenous Arabana “Kupa Piti.” There is some debate about what the words mean; while many think it translates to “White Man in a Hole,” Bruy says it actually means “Boy’s Water Hole.”

When I asked Bruy about the future of Coober Pedy, however, he told me, “I don’t know, but it’s not opal anymore.” Diesel fuel is no longer affordable, and it’s expensive to operate the machinery required in the mines. The opal, it seems, isn’t worth it anymore.

Still, the photographer estimates, about 100 miners have stayed behind in Coober Pedy. Maybe less. Some have been there since the heyday of the opal. The town has opened museums and hotels for tourists, many of which are underground.

The landscape still bears the scars of mining, and people live in subterranean homes. They even pray in subterranean churches. The sandstone keeps them cool and out of sunlight during the blistering hot summers, when temperatures reach 113 degrees Fahrenheit. The hostel where Bruy himself stayed was underground.

The trust of the locals was hard-won. Coober Pedy is no stranger to photographers and journalists looking for a story, and the miners in particular were wary of taking Bruy into the mines. In the end, he thinks his persistence won him their confidence. He stayed in the town for two weeks, then left, but he later returned for two more weeks.

The photographer’s most vivid memories are from the mines themselves. “It’s basically a hole,” he explains over the phone, “Probably 20 meters deep and maybe one meter wide. It’s like going in a well.” Once a miner (or a photographer) makes it underground, it becomes difficult to see and to breathe. There’s dust everywhere.

It’s sometimes hard to know what’s true and what’s false in a town like Coober Pedy. Its desert landscape has served as a backdrop for science fiction and post-apocalyptic films, including Mad Max, Pitch Black, and Beyond Thunderdome.

“It’s full of stories,” Bruy says of the town, “Weird stories.” The weirdest by far are anecdotes from at least 40 years ago, tales of people murdering each other over Australia’s national gemstone. When I don’t respond, the photographer admits, “It sounds crazy.”

But Bruy doesn’t dismiss it as folklore. “Opal can be very precious,” he reminds me, “and you’re in the middle of nowhere.” The chances of getting caught and thrown in jail were probably not high enough to sway a few desperate individuals from violence.

These days, though, things like this don’t happen. Life is peaceful. People go to work. They come home. Maybe, they visit the local golf club. “It’s a quiet town,” Bruy says. Although he says it might be an exaggeration to say “it felt like home,” the photographer did feel comfortable here. He knew people’s names, and they knew his. They shared cups of coffee.

Sadly, the boy William Hutchinson never got to witness the aftermath of his historic find. He accidentally drowned as he was driving cattle, just five years after the opal incident. But a century later, there are still discoveries to be made and secrets to be mined in this rare and unusual place. As for Bruy, he plans to return to Australia this summer, and if he has time, he’ll spend a few days in Coober Pedy, just to check in on all the people he met along the way.

All images © Antoine Bruy