Search this site

Revisiting the Civil Rights Movement in New Photo Book by Steve Schapiro

Along the march for voting rights, Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, 1965.

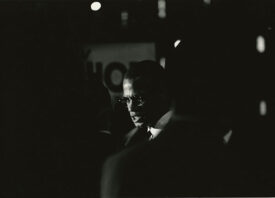

James Baldwin joined the fight for equality in the South. Mostly, he offered a passionate voice for justice and a plea for a nation’s salvation. In Mississippi in 1963, he visited the NAACP’s Medgar Evers, who was slain later that June, following President Kennedy’s landmark televised address on civil rights. This photo was recently discovered in the photographer’s contact sheets.

James Baldwin penned fire to purify truth and liberate it from the lies that have clouded United States history ever since Thomas Jefferson wrote The Declaration of Independence. With every sentence, Baldwin burned away the toxic stench of injustice, oppression, and pathology that so many cling to until their dying day.

One of Baldwin’s greatest works is The Fire Next Time, a collection of two essays originally published by The New Yorker and subsequently published by Dial Press in 1963 in book form. The essays, “My Dungeon Shook — Letter to my Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of Emancipation,” and “Down At The Cross — Letter from a Region of My Mind” address the issues facing African Americans during the height of the Civil Rights Movement, as they faced down the horrors of the past and present each and every single day.

Now, Taschen introduces James Baldwin. The Fire Next Time, a collector’s edition of 1,963 copies reprinted in a letterpress edition with more than 100 photographs taken by Steve Schapiro while he was on assignment for LIFE magazine. Schapiro was on the frontlines of the movement as it marched across the South facing down the system of apartheid under Jim Crow.

The book includes a selection of Schapiro’s best known and never-before-published works from the time including photographs of Civil Rights leaders Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Reverend Ralph Abernathy, Rosa Parks, Fred Shuttlesworth, Jerome Smith, James Baldwin, and United States Representative John Lewis (then chainman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), who wrote the introduction to the collector’s edition.

The book also includes scenes from historic events including the March on Washington, the Selma March, the discovery of the car of Civil Rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman, who were murdered in Mississippi, and Dr. King’s room at the Lorraine Motel to photograph his personal effects on the day he was assassinated by the United States government: April 4, 1968. A selection of works is currently on view at Steve Schapiro: Freedom Now at Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles, through September 2, 2017.

Taken as a whole, Schapiro’s photographs bear witness to Baldwin’s chilling words, the fire so ice cold you can feel the blood freeze inside your bones as he speaks truth to power, telling it like it is: “The American Negro has the great advantage of having never believed the collection of myths to which white Americans cling: that their ancestors were all freedom-loving heroes, that they were born in the greatest country the world has ever seen, or that Americans are invincible in battle and wise in peace, that Americans have always dealt honorably with Mexicans and Indians and all other neighbors or inferiors, that American men are the world’s most direct and virile, that American women are pure. Negroes know far more about white Americans than that; it can almost be said, in fact, that they know about white Americans what parents—or, anyway, mothers—know about their children, and that they very often regard white Americans that way. And perhaps this attitude, held in spite of what they know and have endured, helps to explain why Negroes, on the whole, and until lately, have allowed themselves to feel so little hatred. The tendency has really been, insofar as this was possible, to dismiss white people as the slightly mad victims of their own brainwashing.”

More than fifty years later, those last two sentences read as a red flag, when coupled alongside Schapiro’s evidence of injustice, oppression, and violence that continues to rage. “Slightly mad” would be an understatement of the most gracious kind for Baldwin and any student of American history. We as citizens have inherited the nation’s triumphs, tragedies, and its sins—the stain of blood on the ground everywhere from Staten Island to Ferguson. We live in an era where the issues are as critical now as they were then: from legalized slavery under the 13th Amendment to the destruction of the Voting Rights Act, whose the results were evident in 2016 elections.

It is not merely that there are murderers who walk free among us, licensed to kill. It is that people remain silent in the face of injustice. For those who look to Dr. King as a symbol of progress and peace, he made it plain in “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” the failure and complicity of the white moderate. This fact, Baldwin reaffirms with the plain truth: “The subtle and deadly change of heart that might occur in you would be involved with the realization that a civilization is not destroyed by wicked people; it is not necessary that people be wicked but only that they be spineless.”

Let us praise Baldwin, Schapiro, and all those who risked their lives—and gave their lives—to Civil Rights in the 1960s. Let these images and the stories behind them serve as a reminder of what we must face down today.

Steve Schapiro at work in 1966. There was a sense that the photojournalism accompanying the civil rights movement was helping to inspire the country “in a similar way that perhaps Ferguson has done today,” Schapiro said.

Schapiro’s first stop in Memphis after Dr. King was killed on April 4, 1968, was the rooming house from which the shots were fired. Then he crossed the street to the Lorraine Motel. “The physical man was gone forever, and here his material things remained. It felt like his spirit still hovered above us.”

Twin girls were among those who watched as marchers made history, traveling along Highway 80 and through notorious Lowndes County. The county was 80 percent black, but not one African American there was registered to vote. 1965.

All images: © 2017 Steve Schapiro