Search this site

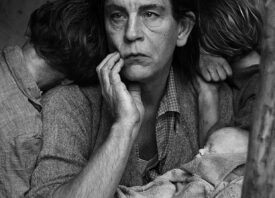

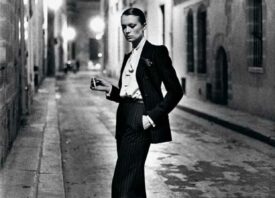

A Photographer and Her Muse Re-Stage History’s Iconic Photos

A tribute to Diane Arbus, A Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street, N.Y.C., 1966

In the beginning, Looking for Masters in Ricardo’s Golden Shoes was just a game played by a pair of old friends, the French artist Catherine Balet and the costume designer Ricardo Martinez-Paz, when they decided to replicate a famous portrait of Pablo Picasso by Robert Doisneau. It was a private little theatrical moment, with Martinez-Paz playing the role of Picasso and Balet casting herself as Doisneau.

Quickly, however, Balet says it became a kind of obsession. The two of them have since painstakingly reproduced some of the most recognizable images in photographic history, with the costume designer embodying the essence of the various subjects, spanning ages, genders, and backgrounds— from Avedon’s “beekeeper” to Capa’s “falling soldier.”

The golden shoes pictured in both the individual images and the book’s title are Ricardo’s own. “He has three pairs, and they are part of his identity,” Balet tells us. They are the single element, aside from Ricardo himself, that is present throughout, and they are also the only things that anchor the work to its creators. Ricardo becomes a character, but he’s never fully lost to or set adrift in the annals of photographic history.

Aside from the shoes, everything from the setting to the fabrics used in the costumes were planned in great detail. It’s surprising to know that all the images were taken in France and England, though the originals come from all over the world. Some of the new locations are convincing “fakes,” but a few are the same.

Les Deux Magots, the café photographed by Saul Leiter in the 1950s, still stands, and Martinez-Paz even borrowed a silver tray from a patron. From the street outside, Balet told him where to stand.

Martinez-Paz executes his performances seriously and earnestly, and so does Balet from the other side of the camera. As her muse tosses of his own identity and tries on another, so too does the photographer. She’s pretend-Arbus, pretend-Mapplethorpe, pretend-Newton. Her genius lies in her ability to transform.

In the end, Balet says the book is about the shifting meanings of photography in a virtual, digital age. It’s about endless reproduction and the infinite streams of imagery that define our daily lives. It’s also an investigation of what it means for a picture to become an icon and a classic, if such a thing is even possible anymore.

Looking for Masters in Ricardo’s Golden Shoes is nostalgic, of course, but it’s decidedly modern too. We’re living in an age in which all things— even photographs— don’t last forever, but that doesn’t mean there’s no reason to hold on. Balet is happy to have her pictures reproduced, but it’s important to her that they always bear the name of their original authors— her many collaborators through time and through space.

Looking for Masters in Ricardo’s Golden Shoes will be on view at the Festival Portraits in France through September 10th, 2017. Balet has exhibitions planned with her Paris gallery, The Galerie Thierry Bigaignon, as well. Find the book here.

A tribute to August Sander, Young Farmers, 1914

A tribute to Robert Capa, Falling Soldier, 1936

A tribute to Willy Ronis, The Little Parisian, 1952

A tribute to Robert Doisneau, Picasso and the loaves, 1952

A tribute to Saul Leiter

A tribute to Richard Avedon, Ronald Fisher, Beekeeper, Davis, California, May 9, 1981

A tribute to Robert Mapplethorpe, Ken Moody and Robert Sherman, 1984

A tribute to Martin Parr, Luxury, 2007