Search this site

These Veterans Are Using Photography to Cope with Trauma

The Visions of Warriors movie poster

At the Menlo Park Division of the VA Palo Alto Health Care System in California, veterans learn photography as a way of coping with trauma. Mark Pinto watches birds out in nature and renders them in blue with his old-fashioned cyanotypes. Ari Sonnenberg takes self-portraits in black and white. Homerina “Marina” Bond photographs blooming flowers–symbols of her recovery. “[There are] tiny little embers of hope buried within the artwork,” Priscilla “Peni” Bethel says. “Every class I attend helps me towards the day those embers will burst into flames.”

The Veteran Photo Recovery Project was founded by Susan Quaglietti, a nurse practitioner at the VA Menlo Park, and she runs the program with help from a team of experts: Jeff Stadler, an art therapist, Ryan Gardner, a clinical social worker, and Kristen McDonald, a clinical psychologist. Together, they work with veterans living with mental disorders. In addition to more traditional, evidence-based treatments, each veteran who chooses to participate creates a portfolio of six images as part of their recovery.

After reading about their work, the Los Angeles-based film producer Ming Lai searched for ways to get in touch with the minds behind The Veteran Photo Recovery Project. In the end, he sent what he calls “an old-fashioned letter,” addressed to the VA Menlo Park, with Quaglietti’s name on it. “Miraculously, she received my letter at this massive campus, and she graciously said yes,” Lai remembers. Three and a half years later, on Veteran’s Day, the people who brought The Veteran Photo Recovery Project to life will share their stories in Visions of Warriors by Humanist Films.

The photographers included in the film are veterans of the Vietnam and Iraq Wars. Each of their stories is different. Some have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and others have been diagnosed with military sexual trauma as a result of assaults that took place within the armed forces. Some struggle with depression or bipolar disorder. At least one retired from the military with moral injury.

All of the veterans included in Visions of Warriors have reached the point in their recovery where they are able to discuss the details of their trauma and their treatment. They agreed to be part of the film, Lai tells me, for a simple reason: “They wanted to help other veterans.” The director and his team traveled to the San Jose area multiple times to meet with the veterans and document their daily lives.

For the veterans and others working through PTSD, photography can work in a number of ways. Holding a camera can force them to “be present” in the moment. As Stadler explains in the film, the act of photographing one’s surroundings gives a feeling of control back to the person behind the lens, and it also helps to alleviate some of the anxiety and hypervigilance that comes with PTSD and related disorders. Capturing the world, the art therapist suggests, fosters an appreciation of it.

Mark Pinto, who now makes poignant staged narrative fine-art photographs with G.I. Joe dolls, credits photography with opening his eyes and anchoring him in reality. “I’m seeing everything,” the veteran says at one moment in the film, looking out from his viewfinder. He puts it simply: “Art is creative. War is destructive.”

The photographs are also used in group discussions as an aid for understanding and processing the journey towards recovery. Some veterans, for example, might be able to confront difficult subjects more easily with images than with words.

Gardner and Quaglietti both told Lai about the importance of protecting and caring for himself throughout the process. “It’s extremely hard to listen to someone tell you about how he had to kill someone or how she was raped or how he tried to commit suicide,” the producer admits. “In making the film, especially during the editing stage, you constantly have to re-experience these strong emotions.”

But while witnessing some of the damage inflicted by human cruelty, Lai also felt his faith in our capacity for good–for empathy, strength, and grace–grow. Remembering the first time she did art therapy, veteran Gail Matthews told him, “For the first time in nearly twenty years, I was smiling.” More than once, a veteran used the word “hope” when talking with him about the future. “Although the veterans are so humble to not think of themselves as heroes,” Lai insists, “This is a heroic act.”

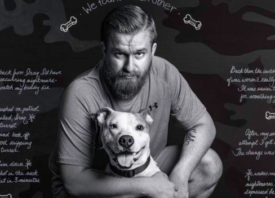

One veteran included in the film, Ramon Ontiveros, dresses as Santa Claus to bring holiday cheer to other veterans at events and gatherings. “With a kind face and long white beard,” Lai says, “He tells them not to give up.” Another veteran, Ari Sonnenberg, whose words are woven throughout the film, was separated from his wife when the film was in development. Since then, he’s reunited with her. He has a playful, affectionate dog, who is also included in the film.

And in addition to the moments of joy he found with the veterans themselves, Lai also coped with the more painful aspects of his subject matter by doing exactly what his subjects did. “I went out and did photography, using all of the concepts that the Veteran Photo Recovery Project had taught,” he remembers. “During my most stressful times, I found it to be very helpful.”

Visions of Warriors will be released on Veteran’s Day, November 11th, 2017 on Amazon Video Direct, Apple iTunes, Google Play, and Vimeo on Demand. Visit the Visions of Warriors website to learn more or to host a screening. Visions of Warriors is produced by Humanist Films.

Susan Quaglietti, Nurse Practitioner and Founder, Veteran Photo Recovery Project.

Ari Sonnenberg, U.S. Army, Veteran.

Ming Lai, Producer/Writer/Director with Gail Matthews, U.S. Air Force, Veteran.

Mark Pinto, U.S. Marine Corps, Veteran.

Homerina “Marina” Bond, U.S. Marine Corps, Veteran.

Priscilla “Peni” Bethel, U.S. Army, Veteran.

Read this next: The Many Uses of Images in Photography Therapy