Search this site

Discreet Portraits of People on The New York City Subway in the 70’s

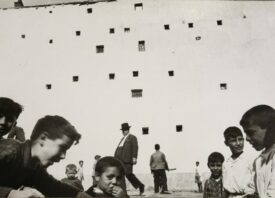

Helen Levitt was an extremely private person and preferred to let her photographs speak for her – and if you listen very carefully, you might just hear the Bensonhurst accent coming through. “Dawling,” a photograph might intone with intimate familiarity, suggesting we come closer to get the gossip or a bite to eat. “Fuhgeddaboudit,” another might insist, making it clear the window for opportunity is firmly shut.

The Brooklyn soul of Levitt is firmly entrenched in her perfectly composed portraits of daily life in New York. Once upon a time before gentrification took hold, New Yorkers were everything America aspired to be. They came from all walks of life, frequently crossing paths, having the good sense not to gawk or to stare because that would be gauche. They came to expect the unexpected and took it in stride, spouting Cindy Adams catchphrase, “Only in New York, kids,” with pride.

They were characters, in every sense of the word, but rarely were they posers because somebody would pull their card. The New York of Helen Levitt spanned seven decades, from the 1930s through 90s, as she walked it streets, discreetly taking photographs without anyone clocking her. She was as much a part of the scene as everyone else, but she was on a mission: to create a body of work in tribute to this big galoot, this metropolis sitting on a pile of schist that would becoming the most powerful city in the world while Levitt walked its streets.

In the late 1930s, Levitt accompanied Walker Evans on trips underground, joining him as he began making a series of photographs on the subway. Evans switched up his large format camera in favor of the newly manufactured Contax 35mm with a wide-angle lens, and began taking photographs surreptitiously to discover the possibilities of photography in a completely new setting.

When the project ended, Levitt’s work went unrevealed. Then, in 1978, a few years after Evans died in 1975, Levitt returned to the trains and began taking a series of photographs as though time had stood still. Photographs from both bodies of work have just been published in Manhattan Transit: The Subway Photographs of Helen Levitt (Walther König) – which includes a rare portrait of Helen herself, made by Evans circa 1940.

The lapse of forty years between the bodies of work is striking for how much has changed – and how much stays the same. One of the most fascinating aspects of the trains, for anyone who has ever ridden one, is this curious space where public and private fuse into one. We are gathered together in an intimate space, hurtling through the bowels of the city, one our way to and fro, lost in our own thoughts. We are checking each other out, getting a lay of the land, while simultaneously trying to mind our own business – because staring is an act of aggression.

At the same time we are surrounded by characters: curious and compelling figures whose lives are mysteries, figures so singular we could easily script personal histories. Levitt’s photographs serve to underscore our desire to look without being seen, to listen in on conversations without fear of being caught eavesdropping.

We read faces, gestures, lips – all the hallmarks of communication that speak without ever uttering a word. We gaze upon the fashions that people wear to adorn themselves, their expression of personality coming through. We see couples caught in moments of magical reverie and we get swept away by a romance that we can feel across space and time.

We see the sourpuss, the lonely and ignored, the judgmental, the pensive and the tired. They could be us; we could be them. There but for the Grace of God go I, like the disco anthem sang. Paging through Manhattan Transit, you can hear Levitt’s raspy laugh, a light nudge in the rib cage as she says, “Would you look at that?”

All images: © Film Documents LLC, courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne