Search this site

The Forgotten Corners of Japan, in Photos

In 2006, the Australian photographer Damien Drew traveled to Shima Onsen in Gunma Prefecture, Japan, to find a sleepy silence had settled over the town. The emerging generation had sought good fortune in the big cities, leaving their hometowns behind. “Many of the hot-spring resort towns around Japan are faded and shuttered,” he admits. The school was no longer running; there weren’t enough young, local children.

Drew didn’t intend to make photographs about the forgotten corners and crevices of Japan. Six years after that initial visit, he took note of the abundance of architectural images in his collection, filled with run-down storefronts, faded signs, and clouded windows. He also recognized parallels between his photographs of the lovelorn shops and houses and those he’d captured more spontaneously on the street. He ultimately strung them together in a series of 96 images, broken into 48 pairs, under the book and exhibition titled Wabi-Sabi.

Influenced by his early studies in architecture as well as the book Wabi-Sabi : The Japanese Art of Impermanence by Andrew Juniper, Drew immersed himself an aesthetic and a philosophy that values imperfection over modernity and the time-worn over the brand-new. Perhaps, he thought, the fact that these places and buildings had thrived for a time and were now in decline made them more beautiful.

Still, the Wabi-Sabi pictures aren’t colored by the anxiety of clinging to what’s already gone. There’s no desperation in a Drew photograph, only acceptance. While he sometimes mourns for the fragility and fleeting nature of our communities and lives, the photographer also rejoices in the fact that they ever existed at all.

Drew knows there are secrets behind his images, and some of them he’ll never know. “As I speak only a little Japanese, it is hard to access the more nuanced parts of these people’s stories,” he tells me. “However, there is a palpable sadness in some of these places.” He saw it over and again, in rural and urban areas across many miles.

In Mito City, Drew learned that when the elderly residents die, there aren’t always descendants to fill their shoes and homes. Even if there are children, they often move on once their parents have gone. “These properties are often left to rot, although a neighbor tending the garden is not uncommon,” Drew says. “I think what drew me to this story was the stark contrast between the ‘tourist brochure’ Japan, characterized by pristine temples and gardens, neon-lit streets bursting with technology and the aging, crumbling Japan that is often only a street away from the polished high streets.”

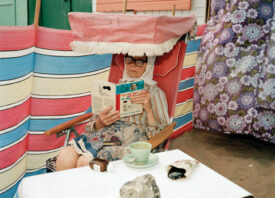

In the last decade, Drew has traveled to Japan seven times. He usually stays in Ryokan hotels or Minshuku (“small family-run guesthouses”). He rarely followed a set routine, preferring to ride and wander from one place to the next in search of magic. He’s gotten to know Japan well–the architecture, the food, the people– and perhaps he’s learned something about his own values along the way. After all this time, his favorite memory is from his early days in Japan, when he formed a friendship with a family, the Hoshimi family, in Mito City. He dedicates the book to them. Follow Drew on Instagram at @damien_drew.

All images © Damien Drew