Search this site

Nan Goldin: The Beautiful Smile

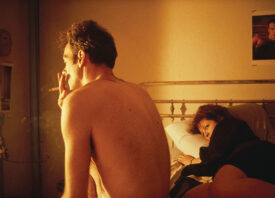

Bruce in the smoke, Pozzuoli, Italy 1995.

Nan one month after being battered, 1984.

Nan Goldin’s photographs are filled with spirits and ghosts, becoming vestiges of lives lived, loved, and lost. They are evidence of we who once were and no longer are, here today, gone tomorrow – were it not for her art.

Over the past five decades, Goldin has created a body of work so iconoclastic and powerful that she has spawned generations of artists who follow in her footsteps, from Juergen Teller to Wolfgang Tillmans and Corinne Day. Goldin first picked up the camera in 1968 at the age of 15, using photography as a means to deal with life following her older sister Barbara’s suicide just four years earlier.

By 1973, she had her first solo exhibition in Boston, wherein she showed the world her travels through the city’s gay and transsexual communities in a series of black and white photographs that are stunningly timeless – yet prescient, as Goldin always is.

“My desire was to show them as a third gender, as another sexual option, a gender option,” Goldin told Stephen Westfall in a 2015 interview for BOMB magazine. “And to show them with a lot of respect and love, to kind of glorify them because I really admire people who can recreate themselves and manifest their fantasies publicly. I think it’s brave.”

Goldin’s admiration for the bold, the fearless, and the gallant permeates half a century of work, a sensibility that is evident on every page of The Beautiful Smile (Steidl). Here, in a brilliantly edited and deftly sequenced monograph. Goldin takes us on a whirlwind tour through her life, giving us a memoir in photographs. From Boston to New York, Brighton to Zurich, Stockholm to Paris, Luxor to Berlin, we are brought behind closed doors and given a glimpse of Goldin’s intense life, one filled with raw emotion, vulnerability, and the pure act of courage to be true to one’s self – for better of for worse.

Using the camera as a means to preserve the ever-fleeting vestiges of memory, Goldin takes us through the glorious glimmers of light that permeate the darkest shadows of life, giving us a look at the indelible impact that each of us has on one another until a strange feeling of familiarity settles in; you may not know any of her subjects personally, but they have subtly transformed before our very eyes from strangers and to kin.

For Goldin, each photograph is a leaf on the tree of humankind, a picture of who we are deep down inside. We are a complex mixture of dualities as one, a place binaries merge, meld, swirl, and fuse until the distinctions between that which is beautiful and repulsive are undone. Goldin’s photographs give us a 360 degree view of life, of the highest highs and lowest lows, and the quiet spaces that dwell in between.

She spares nothing, embracing it all: love and loss, sickness and health, death and rebirth. By taking on issues of sexuality, gender, violence, and drugs without flinching, moralizing, or heroicizing, Goldin’s photographs say all that cannot be said, using empathy and understanding to examine the messiness of life in a manner that suggests unconditional love. It is what it is; it was what it was. Some survived where other perished, and still, we go on.

Barbed wire reflected in pond, Birkenau, Poland 1996.

Guido in the forest, Tulles, Dordogne, France 2005.

Elio sleeping in Guido’s arms, Centre Pompidou, Paris 2007.

Christine floating in the sea, St. Barth’s 1999.

All images: © 2017 Nan Goldin. Courtesy of Steidl.