Search this site

A 97-Year-Old Photographer and Her Love Affair with New York

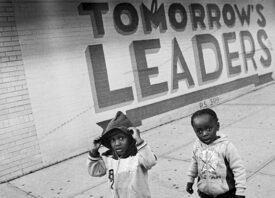

Harlem

Antoinette, Chelsea

“Her photographs are etched into her mind,” the curator Daniel Cooney says of Vivian Cherry, the artist behind the current show at his gallery, titled Helluva Town. Pick out any one of her pictures, and chances are, she’ll be able to tell you the story from memory. Cherry entered the New York photography scene in the 1940s as a darkroom technician when she was a dancer in her early twenties, and she would continue to document her city and its streets for more than seventy years. She lives in Manhattan today.

Cherry’s New York is filled with surprises for the 21st-century viewer, from the fashionable adults on their morning commute to the unsupervised children galavanting about the city streets. As Grace Glueck wrote for The New York Times in 2000, the magic of Cherry’s work from the 1940s and 1950s lies in part in what she calls their “black-and-whiteness.” The Helluva Town photographs could only have been made during these decades. The Third Avenue El, the subject of a large body of work from the photographer and a one-time fixture of the city, no longer stands.

Cherry has watched generations of New Yorkers rise and fade, but it would be a mistake to think of her photographs as existing solely within the confines of history. Julia Van Haaften, the curator at The New York Public Library, reminds us that the photographer returned to many of the sites of her older photographs years down the line. She continued making pictures. Her photos look towards the future as much as the past. In the 1940s and 1950s, they paved the way for an emerging generation of artists; at the time, photography jobs for women were scarce.

Cherry always chooses honesty over sentimentality. In an age that revered picture-perfect suburban domesticity, she opted to photograph children run amok, playing games their parents likely would not have condoned. She witnessed children fighting in make-believe gun fights, in most cases, she was probably the only adult to have taken notice. “There’s kind of a violent tone,” Cooney tells me about some of Cherry’s photographs of children. “One we can all remember from when we were children.”

Of course, Cherry would not have been able to predict the longevity of her images at the time she made them. As a street photographer, she was constantly on the move, chasing split seconds of beauty and sorrow. But it’s typical of this photographer to capture slices of New York City that reach through time to reassert themselves to a new audience, even if she never consciously intended them to do so. Tellingly, the grandson of one of Cherry’s subjects showed up at one of her exhibitions a few years ago to meet the photographer. “Her instinctive eye zeroes in on what is most salient about a scene, a gesture, a point of light, the cast of an eye,” Van Haaften tells me. “Her inner vision operates her camera.”

There’s a photograph from Harlem in the 1940s. Three girls look up at the sky, in awe of an airplane passing overhead. While everyone else was taking in the spectacle, Cherry turned her eyes to the people in the background. It’s something she would continue to do for many years to come. As for the woman herself, the photographer remains young at heart. She’s deliberate about her photographs and the way she wants them to be seen. “She’s very much in charge.” Cooney says. She laughs freely over the phone, and she seems to live without pause, as if she’s constantly on her way from one place to another. Like a true New Yorker, she’s always impeccably dressed. “I’m ninety-seven,” she told the gallerist early on in their collaboration. “Isn’t that wild?”

See Vivian Cherry: Helluva Town through June 16th at Daniel Cooney Fine Art.

3rd Avenue EL (Girl and scarf)

Game of Guns II

Game of Guns IV

3rd Avenue EL (Man)

Sicilian Man

3rd Avenue EL (Man at Dentist)

Baked Beans