Search this site

The Horrors of the Illegal Wildlife Trade Revealed in Photos

Zebra Bookend, 2018

Stacked Turtles, 2018

Bear Gallbladder with Bosc Pears, 2018

Take a look at Christine Fitzgerald‘s still life with pears, and you might mistake it for an antique; after all, it was created using a 19th century photographic process. But if you dig beneath the surface, you’ll find something unsettling about this particular tintype: one of the “pears” isn’t a pear at all. It’s the gallbladder of a bear. “Bear parts, including paws, gallbladders, and genitals, command great prices on the black market,” the Canadian photographer tells me. Her series TRAFFICKED takes a fresh and unlikely approach to the horrors of today’s illegal wildlife trade, bringing us face-to-face with the objects confiscated by the Wildlife Enforcement Branch of the Canadian Government.

“I feel a profound sadness about what humans do to wildlife,” the photographer continues. “The illegal trade of wildlife is horrific. It’s about human greed, ignorance, and indifference.” Moved by photographs of animals brutally killed by poachers, she longed to contribute to the conversation, and because the problem affects all corners the world, she knew she wouldn’t have to travel far. With permission from the head of the Wildlife Enforcement Branch of the Canadian Government, Fitzgerald was able to set up shop at a “secret, locked location” where items are held after being seized at the Canadian border. “He told me that I was the first artist to request access to the specimens,” she remembers.

The wet plate collodion process is labor-intensive, and Fitzgerald spent long days alone with her subjects. “I had access for as long as I wanted,” she explains. “I set up my darkroom on site with a portable fishing tent and set up studio lights for shooting. The location was ideal for what I was doing as there was a stainless steel counter with a sink and a high-powered ventilation system. An assigned staff officer would check-in on me from time to time.” She made the images by hand, and when it was all said and done, she returned home exhausted. “Some days I only create one plate that I am satisfied with,” she admits. “It’s not easy.”

The pace of the process itself left her with time to reflect. “I think it was the magnitude of the problem that stuck with me,” she tells me. “The statistics are staggering. The illegal trade of wildlife is estimated to be a $22 billion USD industry.” She did not have access to information about the individual specimens and the circumstances under which they were confiscated, but the gravity of the situation hit her hard. Behind every object, there was once a living creature, and Fitzgerald’s photographs seem as organic and fragile as the materials she documented. “The exposures are long and the process prone to random imperfections,” the artist says.

Because of TRAFFICKED, we can remember the tens of thousands of animals who are killed illegally each year. This photographer has borne witness, and by following her example, we too can advocate for change. As a child, Fitzgerald spent her free time roaming the woodlands of Québec, where she learned to respect the creatures with whom we share our planet. Even now, after all she’s seen, she finds comfort in the natural world. Despite all that humankind has taken, the Earth and its many inhabitants continue to offer us hope. “Every time I explore nature, I am reminded that we are such a small part of a complex and interconnected world,” Fitzgerald tells me.

Duck No. 1, 2018

Lynx rufus, 2018

Ivory Bracelets on Tusk, 2018

Saiga Antelope Horns, 2018

Crocodile Claw, 2018

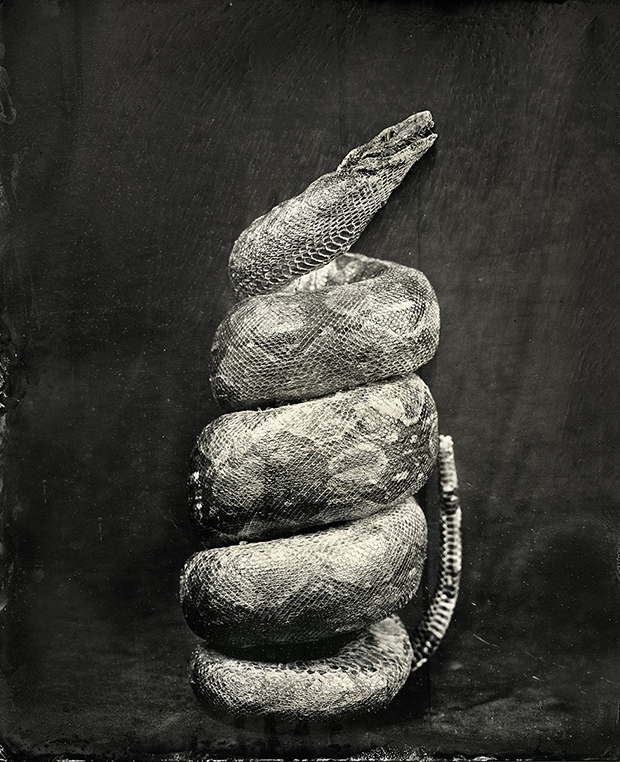

Coiled Snake, 2018

Rhino Horn on Plate, 2018

Platter of Duck Wings, 2018

All images © Christine Fitzgerald