Search this site

A Portrait of the Amazon on the Brink of Catastrophic Change

March 29, 2014. A group of boys climb a tree on the Xingu River by the city of Altamira, Para State, Brazil. Major areas of the city have been permanently flooded by the construction of the nearby Belo Monte Dam Complex displacing over 20,000 people while impacting numerous indigenous and riverine communities in the region.

November 26, 2014. Members of the Munduruku indigenous tribe walk on a sandbar on the Tapajos River as they prepare for a protest against plans to construct a series of hydroelectric dams on their river in Para State, Brazil. The tribe members used the rocks to write ‘Tapajos Livre’ (Free Tapajos) in a large message in the sand in an action in coordination with Greenpeace. After years of fighting, in 2016 the Munduruku were successful in lobbying the government to officially recognize their traditional territory with a demarcation. This recognition forced IBAMA, Brazil’s Environmental Agency, to suspend the environmental licensing process for the 12,000 megawatt Tapajós hydroelectric complex, due to the unconstitutional flooding of their now recognized land.

The mouth of the mighty Amazon River lies in the state of Pará, Brazil, which has been home to the people of the rainforest for over 5,000 years. During the 1960s, the government created the nation’s very first Indigenous Park, which was, at that time, the largest preserve in the world.

Home to 14 tribes that survive off the land, Xingu Indigenous Park became the site of controversy when the government began to develop plans for the Belo Monte Dam Complex on the Xingu River in 1975. In 1989, the Kayapo, a warrior tribe, mounted a massive campaign in opposition to the construction. International financers pulled out, and the project was shelved until 2007, when President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva announced the Accelerated Growth Program.

Positioned at the forefront of construction of more than 60 major hydroelectric project in the Amazon over the next 15 years, Belo Monte is poised to become the fourth largest dam in the world — displacing up to 40,000 people living in the park while destroying the complex ecosystems in order to fuel continued mining of the rainforest.

In his series, Where the River Runs Through, which was chosen for the Critical Mass Top 50, photographer Aaron Vincent Elkaim presents Where the River Runs Through, a profound portrait of the people and the landscape at the precipice of a massive change whose impact on the indigenous communities and the environment are devastating. Elkaim shares his insights into the impact of industry on the earth.

Could you speak about the inspiration for this project – how did you learn about the Belo Monte Dam Complex, and what led you to get involved?

“Where the River Runs Through has become the second project in what is turning out to be a series of stories focusing on indigenous and land based communities living on the front lines of extractive industrial projects. The first project, Sleeping with the Devil, focused on the community of Fort McKay First Nation as it deals with life in Canada’s environmentally destructive Oils Sands industry.

“With an educational background in cultural anthropology, I have a general interest in exploring human cultures and as a documentary photographer, a desire to work towards social justice steers my work. I have always had a deep personal relationship with nature and through following my interests and instincts have been drawn towards stories where environmental justice and social justice collide.

“The Amazon Rainforest is a place that captures the imagination, since I was a child I remember being drawn to it, and as an adult it was a place I knew I would one day visit. I first learned about Belo Monte through an online news article as I was finishing up my project Sleeping with the Devil, and it immediately caught my interest. I began to dig further, and before long I knew this story that was going to take me to the Amazon.”

March 23, 2014. Mutton birds are seen at a families home on the Iriri Extractavist reserve in the Xingu Basin. Extractavists are the descendants of Rubber Tapers who came to the forests generations ago during Brazils Rubber Boom. Days away by boat from the city of Altamira, they live along the river banks with an economy based on harvesting sustainable natural products such as rubber, nuts, and oils. Many of the Belo Monte Dam’s impacts have been indirect to the Extractavists, such as commercial fisherman who now need to travel further away from the impacted Xingu, are beginning to over fish the rivers these people depend upon for food.

Could you provide our readers with a brief overview of the history of the Belo Monte Dam Complex and the issues its reinstatement presents to the environment of Brazil?

“Plans for the Belo Monte dam began in 1975 under Brazil’s military dictatorship, it would have been comprised of five dams and would flood over 18,000 square km. In 1989 attempts to construct it were delayed when indigenous protests by the Kayapo tribe, who live 500km upstream on the Xingu River, created an international outcry. But as one engineer said ‘God only makes a place like Xingu River once in a while. This place was made for a dam.’

“In 2007, under the government of Lula da Silva, he announced the Accelerated Growth Program, the largest investment package to spur economic growth in Brazil in over 40 years. A cornerstone of the program was the industrialization of the Amazon, with the construction of dozens of major hydroelectric projects and a redesign of the Belo Monte Dam at the forefront.

“To gain environmental approval for Belo Monte they redesigned the complex reducing the number of dams from five to three with a new reservoir of 500 sq km that avoids the direct flooding of indigenous lands. It is a run of river dam that diverts 80% of the Xingu River along the Volta Grande or Big Bend, where the Juruna, Arara and Xikrin tribes live.

“These are the most directly impacted Indigenous groups. Their fish stocks have plummeted, their water polluted and their ability to navigate the river impeded. Construction began in 2011 and is slated to be fully operational in 2019. Many other regional tribes and traditional riparian peoples, such as fisherman and rubber tappers that have lived in the region for generations have also been displaced or impacted.

“The Complex is considered to be the fourth largest hydroelectric project in the world by generating capacity. It is also going to be one of the least efficient hydro-power projects in the history of Brazil, producing only 10% of its 11,233 MW capacity between July and October – On average it will produce 4,419 MW throughout the year, or 40% of capacity. Future dams to increase production are still possible but are currently not openly planned.

“The energy generated will power cities thousands of miles away, with power lines cutting through vast swaths of forest, as well as fuel regional mining initiatives, such as the proposed Canadian owned Belo Sun, which would be Brazil’s largest open pit gold mine located only a few km from Belo Monte. It has also been reported that the Belo Monte dam was used to generate 150m reais ($41.4m) in donations to the ruling coalition at the time, highlighting the corruption potential present in these large infrastructure projects.”

December 15, 2014. Munduruku women bathe and do laundry in a creek by the village of Sawre Muybu, on the Tapjos River in Para State, Brazil. The Munduruku are a tribe of 13000 people who live traditionally along the river and depend on fishing and the river ecosystem for their livelihood. They have been fighting against government plans to construct a number of hydroelectric dams on the Tapajos River in the Amazon rainforest that would flood much of their traditional lands.

Can you share background about the Munduruku tribe – who are they, how does this initiative effect them, and how have they been able to successfully fight back?

“The Munduruku are a warrior tribe of 13,000 people on the neighbouring Tapajos River where the 12,000 MW Tapajos Hydroelectric Complex had been planned. They had been allies in the fight against Belo Monte, engaging in protests and occupying the construction site in 2013. The Tapajos Hydroelectric Complex would have flooded a large portion of their traditional land that had not yet been demarcated.

“To stop the dams they self demarcated their lands using hand held GPS, machetes and chainsaws until the government of Dilma Rousseff finally gave them official demarcation just before being impeached. The demarcation led to the project being unconstitutional, as it would flood indigenous lands. Soon afterwards IBAMA, Brazil’s environmental agency, cancelled the licensing process for the dam in a huge victory for the tribe and river.”

Could you speak about the challenges you faced making this body of work, as well the rewards that have come about as a result of meeting those challenges?

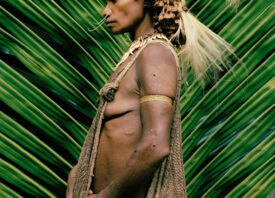

“I think of the challenge that faced me early on while creating this work was the notion of representing and documenting the ‘other.’ Indigenous and traditional communities have a romantic appeal, and as an outsider, a white person from a country with its own colonialist legacy, the issue of representation was something that I struggled with. In many ways, I wanted to resist the temptation of showing these communities in a romantic light, but as the images began to take shape, I realized that my strength as a photographer is finding the beauty in the everyday, and there is inherently romanticism in that approach.

“I think it is so important to reflect on these notions of representation and have that reflection inform you, even if only on the subconscious level. I observe and react, and what causes me to react is instinct based in the subconscious. This challenge, I think, led me to question my instincts, which in the end led me to trust them.”

December 5, 2016. Ana De Fransesca and her son Thomas, visit the Belo Monte Dam site, which will be completed in 2019 on the Xingu River in Para state, Brazil. De Fransesca is an anthropologist that has been working for a local NGO, Instituto Socioambiental, while doing her PHD on the displaced riverine communities and fisherman impacted by the dam.

Could you speak about the conflict that many developing nations face in dealing with industrialization during a precarious time in the early years of the Anthropocene Era?

“There is an assumption that industrialization is progress, that development is progress, and I suppose it is from the perspective of a nation, but certainly not always for groups of people. A nation wants power, they want capital, they want growth; as part of the global capitalist system they need these things. But so often these things come at the expense of people who live outside of that system, those who live simply and sustainably off the land.

“I don’t really think it matters if a country is developing or developed, the thirst for growth within this system is unquenchable. A developed nation is just as likely to squeeze capital from its natural resources as a developing country. We see this in Canada and the US with fracking, the oil sands, hydroelectric development and off shore drilling. With a developing country there is the excuse that they need to catch up to our standard of living, but I see this as a tragic fallacy. Nations that still have their environments in tact have something of value that much of the developed world has lost and with it they have the opportunity to create sustainability.

“Once a river is dammed or a lake poisoned, that resource is forever gone, but intact it can give its wealth forever, if properly managed. The challenge is finding democratic sustainability by utilizing healthy ecosystems for the common good. In truth people don’t need so much, they need clean water, shelter, education, access to medical care, freedom of culture and an ability to feed themselves. What industrialization often does is take away the clean water, the ability to feed themselves, and with that freedom of culture. In return they get a promise that the system, with its new prosperity, will provide for them. It rarely does over the long term, and those who once had the freedom to live from the land, as their families and culture had for generations, often become slaves to a system just to meet their basic needs.

“We are becoming aware that our system of endless growth is unsustainable; the earth does not have infinite resources or ecosystems, yet we continue to exploit all that remains, with continued promises of prosperity. Terms like ‘developing, development, and progress’ are meant to have positive associations in our minds, used to drive this cancerous growth, but those whose lands are disrupted by it, would often use the term ‘destruction’ instead. Natural healthy ecosystems are the wealth of the people; ‘resources’ are the wealth of the power brokers. That’s the system we live in, and we all need to recognize our complicity by believing our unsustainable comforts are our right…. even more than people have the right to clean water.”

March 19, 2016. A Munduruku indigenous girl with her pet monkey in the village of Sawre Muybu, on the Tapjos River in Para, State, Brazil, is seen in traditional paint preceding a ceremony the day after an action in coordination with Greenpeace in protest of plans to construct a series of hydroelectric dams on their river in Para State, Brazil. The Munduruku are a tribe of 13000 people who live traditionally along the river and depend on fishing and the river ecosystem for their livelihood.

April 5, 2016. Cassici, or chief, of the Juruna indigenous tribe, Gilliarde Jacinto Juruna, leads an indigenous occupation of the offices of Norte Energia, the company building the Belo Monte Dam, in the resettlement district of Jatoba in the city of Altamira, Para, Brazil. Occupations and protests are a constant part of the regional indigenous communities fight for compensation and promised programs from the company. The Juruna live on the strech of the Xingu River known as the Big Bend, which has had 80% of it’s flow diverted by the dam impacting their fishing, river navigation and overall sustainability.

November 11, 2016. Juruna from the Paquicamba Indigenous Reserve are seen at a public audience where riverine communities were able to voice their grievances to the Public Ministry and Notre Energia, the consortium in charge of building the Belo Monte Dam. The Juruna live on the stretch of the Xingu River known as the Big Bend, which has had 80% of it’s flow diverted by the dam impacting their fishing, river navigation and overall sustainability. They are now fighting to stop the proposed Belo Sun gold mine that would be 11km away from their village and would be the largest gold mine in the country. While the environmental impacts of Belo Monte are still being analyzed, licensing for the mine hasn’t taken into account any potential cumulative impacts to the river or the people who live upon it.

All images: © Aaron Vincent Elkaim