Search this site

Powerful Portraits of People Living in Purgatory at the US and Mexico Border

A teenage migrant boy, Jesus Martinez Stadium, in Mexico City, Mexico, Nov 9, 2018

Migrant children playing in the streets where they are camped out, outside the locked gates of the condemned refugee camp, Benito Juarez sports complex in Tijuana, Mexico, Dec 2, 2018

In November 2018, Cory Zimmerman began documenting the lives of people living in purgatory, just across the US border into Mexico, in places we rarely see or consider from the inside looking out. Over the next three months, Zimmerman created a series of photographs titled Between a Sword and a Wall: A Portrait of he Migrant Caravan, made at the front lines of the migrant crisis.

Zimmerman traveled to Jesus Martinez Stadium in Mexico City, the Benito Juarez sports complex in Tijuana, San Ysidro border crossing in Tijuana, and the US/Mexican border at Playas de Tijuana as part of an ongoing effort to assist and document the lives of the people who are fighting for their lives.

Zimmerman started a Go Fund Me to help feed the children, as his current work takes him to Guatemala, where he is working with NGOs to document the causes behind the on-going migration crisis. Here, he speaks about his experiences photographing the innocent people whose lives hang in the balance.

The US/Mexican border fence with newly installed razor wire, Playas de Tijuana, Mexico, Dec, 5, 2018

How did you get involved in documenting the Between a Sword and A Wall?

“I have been living and working as a photographer in Mexico City for the past couple years. When the first migrant caravan arrived here to the city, I wanted to go to the shelter, which was a football stadium converted into a makeshift refugee camp, and document what I could.

“As I approached the gate to the stadium, I noticed was a hoard of people jumping out of the back of a semi trailer. Everyone immediately walked into the gates with their belongings and children, in search of food and shelter. But there was one boy who went immediately for the curb and he just sort of collapsed in exhaustion.

“I had a few granola bars in my bag and I approached him and handed them to him, and then asked him if I could take his portrait. This was the first photo I took that day. Then I entered the camp, and as I walked around taking photos. Eventually, children began to follow me, many smiling, giggling and hyper, but others sad, dirty and weak, but all of them were begging me for food, and it broke my heart that I did not have any to give them.”

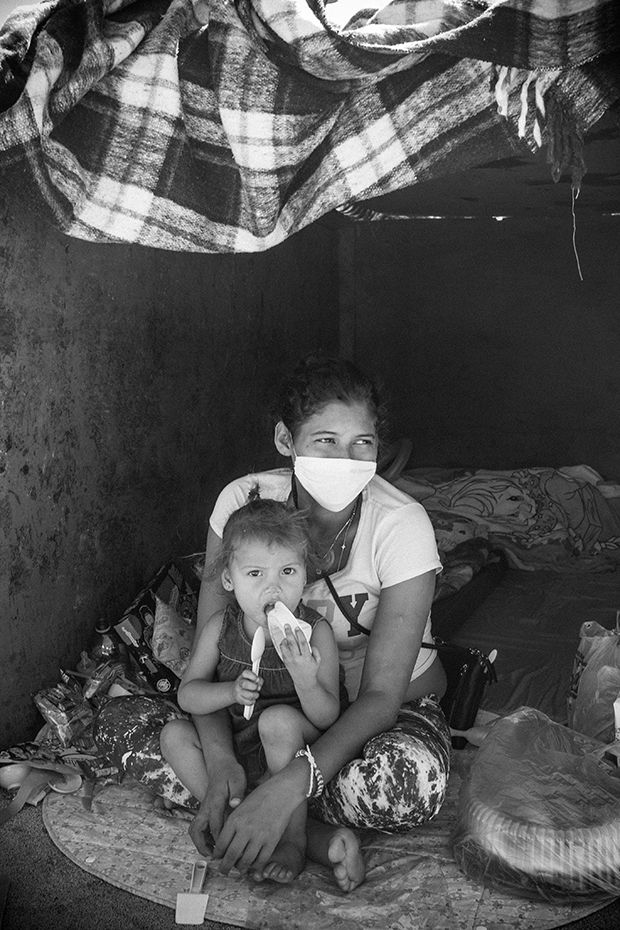

A migrant mother holds her child in a make shift shelter, Jesus Martinez Stadium in Mexico City, Mexico, Nov, 9, 2018

Could you tell us how you came to connect with Argentina and Jonathan?

“When I arrived home that day, I was going through my photos, and I kept returning to that photo of the boy on the curb too weak to stand, and I could tell something was not right. I also kept thinking of the children begging me for food. I then felt that the sanest thing I could do was try to help them in someway, to feed them in anyway I could.

“I posted a few photos on FB and I began to ask for donations. Then the next day, I went back to the camp to take more photos and to check on the boy, but after asking around I discovered his mother had rushed him to the hospital. I left a note instructing the mother to call me.

“Over the following days, I was surprised by how much money I was able to raise, how much support was truly out there for these people in spite of the hate filled and fear mongering propaganda, in particular of them being an ‘invading force.’ Each day when I would go to document, I would take loads of food with me to the camp, feeding as many children possible.

“Finally, I got a call from the mother. Her name was Argentina. They were from Honduras. She informed me of the severe medical condition her son, Jonathan, was in, and I feared he would not make it by foot the thousand miles they still had to trek through Mexico’s most notorious regions toward Tijuana.

“I bought a backpack and filled it with clothing, supplies, a blanket, and healthy food, and then I bought the mother, the boy, who is seven and his two young sisters, bus tickets. At first she feared it was a trick and that I may be involved with human trafficking, but I finally convinced her of my pure intentions, and the very day Jonathan was released from the hospital they boarded the bus and headed north.

“A week later, I flew to Tijuana to meet them. As I tried to track them down, I made daily trips to a park that had been set up as a refugee camp that was situated right on the border – you could see the border fence right across the street.”

A young migrant child sits outside of her family’s tent on the sidewalk outside of the locked gates of the condemned refugee camp. After a week of rain, the camp flooded with sewage and the authors were forced to relocate the migrants out onto the street. Those who volunteered where bused south to another shelter a 45 mile drive south of the border. But many families chose to stay camped along the border, where they held firmly onto their American dreams. Benito Juarez sports complex in Tijuana, Mexico Dec 1, 2018

What happened when you arrived at the camp?

“The camp was being shutdown due to sanitary reasons, as rainstorms had caused human waste to pool up, and the smell was horrific. By now most of the migrants had been pushed out and they were living in tents and make shift shelters in the streets surrounding the park.

“I documented what I saw, which was beyond words. Those who were willing, were bused to an old abandoned nightclub, a 45 minute drive south from the border, where the living conditions were a living nightmare. Thousands of migrants, in a very dangerous part of southern Tijuana, in an enclosed space that had no fresh air, despite the growing cases of TB amongst the group. Also there was no electricity, and no running water to bathe or use the bathroom.

“I chose to stick mostly with those remained near the border, those living on the street, waiting for their number to be called, the number written on their arm by authorities at the crossing. Meanwhile the children were starving, and the simple truth is that people were starting to die. One child died on Christmas day, and I even saw a dead body in the camp one day, being heaved into the back of a truck like garbage.

“Daily I made four, five, or six trips to the camp bringing loads of food for the hungry children, as there were hardly any services set up by this point to provide any sort of aid, let alone food. The children were always very excited to see me, and they loved apples the most, always yelling, ‘Manzana! Manzana!’ as soon as they saw me approaching, running up to hug me, with huge smiles.

“Children are tough, and many were joyful and played in the streets, but nonetheless, they were starving. And the healthier kids would grab me by the hand and pull to where ever a child too weak to play or walk would be hidden away, so I could feed them. They certainly made it a point to take care of one another.”

The first time I saw Jonathan, he had just crawled out of the back of a semi trailer. He immediately collapsed to the curb out of exhaustion as he clutched his toy car and a few granola bars I gave him, Jesus Martinez Stadium in Mexico City, Mexico, Nov, 8, 2018

How did you find Jonathan again?

“Then one day as I walked out of a market, I saw Jonathan sitting on the curb, and then I looked up and saw his mother and sisters, and we both very happy to see each other. The weather was warm, but Jonathan still had on the winter coat I had bought him, and his mother Argentina told me he said it was a good luck charm, and refused to ever take it off.

“I could see that Jonathan was still very sick and could barely stand, and Argentina told me that he had been in and out of the hospital a few times since I last saw them. I bought them lunch and then purchased every medication scribbled on the prescription forms Argentina had in her pocket, for Jonathan.

“While in the pharmacy, Jonathan laid on the floor, unable to stand. Knowing Jonathan needed proper and immediate medical care, we luckily found a group of volunteer immigration lawyers from San Diego who helped them with their paper work and then escorted them to the border, where their plea for asylum was forced to be recognized.

“They appeared before a judge, and due to Jonathan’s illness, they were one of a very small percentage of migrants legally allowed into the USA. Argentina was given a pending court date, and they placed an electronic ankle bracelet on her ankle. We found her a sponsor family in New Orleans, and I managed to quickly raise more money, and bought them bus tickets to Louisiana where they are now in a healthy and safe environment.

“I contacted a local charity group for refugees to assist them with their immigration hearings, and to provide Jonathan his much needed medical care. I keep in touch with them as often as possible, and still did all I can to help while they waited out the government shutdown, since the immigration courts are barely operating.

“I am currently raising more money to send them a care package, because knowing Argentina is not allowed to work or leave the house at all, except to check in her electronic bracket at the court once a week or so, I am not sure how they are eating. I tried to feel good about what I had done, but it was difficult to feel any joy through the immense amount of sadness I felt after witnessing such suffering. But on the day they arrived to Louisiana, Argentina sent me a message, and asked me if I would be the godfather to her children, and I could hear in the back ground the kids all shouting ‘Hi godfather!’…and then in that moment, I was able to feel joy.”

Jonathan’s sister after just feeding her family and meeting with volunteer immigration lawyers who offered to assist them in applying for asylum. San Ysidro border crossing in Tijuana, Mexico, Dec, 5, 2018

Why do you think it is so easy for American citizens to blame the victims of our horrific foreign policy?

“I believe it is the natural inclination of any empire to at one point or another fall victim to the impulse and ease to colonize if not conquer weaker states and nations. The amount of exploitation and intervention that has taken place in Central America is no surprise to me. I think the irony is that the Monroe Doctrine was initiated by a nation that at that [point] in history followed a doctrine of anti-intervention, and that the interpretation of the doctrine itself has been turned inside out, no doubt with conscious intent, and that atrocities ensued.

“The problem now is the amount of ignorance among the American people as to the amount of negative impact the United States has had on Central America, how responsible we are in major ways, including the backing of dictatorships, initiating and funding of civil wars, which included the influencing of scorched earth policies to devastate Central America. These topics are not general topics taught in school. They are very specialized subjects that would have to be sought out. Additionally, the US has never been in favor of teaching its own people of its own flaws, let alone the atrocities the nation has committed, including the genocide of Native America.”

Argentina, Jonathan and his two sisters sit not he curb in front of a market where I finally happened to find them. I was happy to see that Jonathan made the journey in spite of his health issues. Tijuana, Mexico, Dec, 4, 2018

Could you speak about the title Between a Sword and a Wall?

“The best way to describe how I came up with the title Between a Sword and a Wall is to show you a transcribed interview I had with Argentina in Tijuana, when their fate was still in the air:

“’My wish is to be in the US to get Jonathan the treatment he needs, that is my dream. My brother died from untreated anemia, and it hurt me a lot because he had so many dreams. I was with him all the time in the hospital and now I am doing the same with my son.

“’I don’t want Jonathan to go through the same suffering. It worries me because he has gotten sicker and sicker. Last year he was in a coma for a month. I want so badly to have control over his meal times, but when I go in search of food, there is often nothing.

“’It has not been easy on Jonathan and that scares me to death. I wish I could have a place on my own and to be calm. I wish we could be on the other side already. There are moments in which I get worried and desperate, in the name of Jesus, I pray this ends soon. It has not been easy.

“’The roads we have walked down we have suffered. I have seen women badly beaten on the street and left behind to their fate. Then, with Jonathan’s health scares, we’ve had so many horrible experiences along the way. It’s been rough, to be neither here nor there.

“’Back in Honduras, I suffered domestic violence and my two eldest daughters were sexually abused, and I don’t want my two little girls to go through the same nightmare. I want a future for my children.

“’They all three love football, and Jonathan loves to play the drums. You see, my children have dreams of their own, and I wish to get to a place where they can develop those dreams, those dreams of their own, and to be someone in the future.

“I’ want to work, and put my kids in school where they can learn many things. I would like that very much. That is my dream and I pray god will give me the wisdom to show me the way to the other side. But now, I do not know where to turn, where to search for refuge.

“’In a simple truth…I am between a sword and a wall.’”

A young migrant girl, who inspire of the hardships she has endured, grins a beautiful smile for the camera, Jesus Martinez Stadium in Mexico City, Mexico, Nov, 9, 2018

A young migrant girl with piercing eyes who loved apples, “Manzana! Manzana!” she would yell when she saw me. She always wanted to touch my blonde hair. The children were all infested with lice, but I let her anyway. Benito Juarez sports complex in Tijuana, Mexico, Dec 3, 2018

Jesús Martínez Stadium, Mexico City, Jan 28, 2019

All images: © Cory Zimmerman