Search this site

A Multi-Faceted Portrait of the Genius of Photographer Jim Marshall

Man outside a liquor store in Oakland, California, 1962

Black musicians still had to fight to perform in venues in non-black neighborhoods, even though the black and white locals of the American Federation of Musicians had merged. North Beach, San Francisco, 1960.

John Coltrane listening to playback at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio for Impulse Records, New York City, 1963

When most people think of photographer Jim Marshall (1936-2010), scenes from rock and roll history come crashing to mind: Jimi Hendrix setting his guitar on fire during the Monterey Pop Festival; Johnny Cash flipping the bird at San Quentin State Prison; Janis Joplin lounging like a vixen in a sparkly mini-dress with a bottle of Southern Comfort in hand; the Charlatans playing the Summer of Love concert in Golden Gate Park.

But Marshall’s roots go deeper than rock: they thread through the history of jazz, in the nightclubs and festivals where he honed his skills as self-taught photographer coming of age in Jim Crow America. A perennial outsider, Marshall championed the underdog, the spaces where the oppressed and exploited transformed their pain and sorrow into beauty and art.

As a man of the streets, Marshall understood the power of the activist to transform the way we see and think. He used the camera as his instrument, to tell the story of the people and the times — not just the headlining names but the regular folks who fought for the cause that we’re still fighting for more than half a century after he made some of his most indelible photographs.

Thelonious Monk and his family in their apartment’s kitchen, New York City, 1963. This photo was shot for a Saturday Evening Post story.

Amelia Davis, Marshall’s longtime assistant and editor of Jim Marshall: Show Me the Picture – Images and Stories from a Photography Legend (Chronicle Books), has put together a stunning tribute to Marshall’s vision of life during the twentieth century. She pairs Marshall’s photographs with incredible essays that take us along for the ride, giving us a powerful portrait of the exquisite genius that is Marshall’s singular legacy.

“It was so very personal. It was meant to accompany the documentary film Show Me the Picture: The Story of Jim Marshall but also be a stand alone book. I wanted it to be intimate and personal to show who Jim Marshall was. Most people know him for the rock and roll photography, and he was so much more than that. He was so compassionate and empathetic but that wasn’t the person everybody saw and I wanted to show that in the book.”

Here Davis shares her insights into Jim Marshall — the man, the myth, and the force of nature.

Can you talk about Jim Marshall and the way his work reflects the intersection of who he was as a person, an artist, and an activist?

“Jim was an immigrant. His parents would always call themselves Assyrian. He was born in Chicago but when he was one or two, they moved to San Francisco. His dad left him and he was brought up by his mom and his aunts. They lived in a district that was the jazz neighborhood. He always felt like an outsider. He looked foreign. He had that chip on his shoulder but because of that he was always representing the underdog and wanted to show them for who they were and give them the dignity he felt they deserved through his photographs.

“Jim was self-taught. He bought his first Leica for $50 down in 1959 and started photographing. Because he didn’t have anyone telling him what to do, he could go into jazz clubs in North Beach. It was dark and he had an all manual camera with a fixed lens and most of the musicians were black so you had a dark environment with black skin and he was able to look at that lighting situation and know exactly what shutter speed and F-stop to put it on and he knew it would come out. He had to know because in the early days he was broke. He would buy bulk film and roll it himself. He couldn’t waste the film. He didn’t have the luxury of being able to click away and hope something came out.

“When the Haight-Asbury counterculture started happening in 1965, he was there to document it from the very beginning up until it ended and went into the 70s. What I found very unique about Jim is that during that period of time, all the other photographers were there for the music so if Jimi Hendrix was doing a free concert in the Panhandle, they would photograph Jimi and when the song was over, they’d put their equipment away and leave. Whereas Jim would keep his camera out and start photographing everything that was happening around it. For him, it was the whole experience, not just the music. He wanted to immerse you in everything that was going on around at that time.

“Even with the peace symbol and Civil Rights. When Him went down to the South, he was in the Newport Jazz Festival to photograph Joan Baez in 63/64. She went down to the South to do trial run marches on Washington and they were trying to sign up Blacks to vote. Jim followed her down there and then captured this incredible early Civil Rights movement that was happening. He seemed to be everywhere that mattered,. He had his camera with him and he was able to document it all.

“I am trying to share with the world who Jim was. You may have thought he was one person but after going through this book you see he was so much more than that. When photographers die, their archives are locked up and put away, and nobody gets to see them again. Jim photographed people and histories that will never happen again, and his work is too important not to share with the public. One of my goals through the books and shows that we do is to show all his work and the pieces of history that he captured because they are so important right now.”

Miles Davis, the Fillmore, San Francisco, 1971

Woman in the audience at “The Greatest Gospel Event in History,” held in Randall’s Island Stadium, New York City, 1963

Can you speak about how he used photography as a medium for cultural, political, and social change – and how this reflected the spirit of the music and the times?

“It’s all interconnected. The Beats of the 1950s were in North Beach, and as it was moving it into the ‘60s, they took their writing and added music. Then Jim was there adding his camera documenting the music and the words, and what was going on. It is all connected, especially with his jazz.

“When you look at his early jazz at these festivals, especially Monterrey Jazz Festival or Newport Jazz Festival, at that time the US .w.as still segregated and those were the only places where white and Blacks could mingle and not be harassed by the police because they were there for the universal language of music. Jim not only photographed the musicians, he also photographed the crowds. It is incredible because there you see Blacks and whites together, not having to worry, just enjoying the music and it says so much.

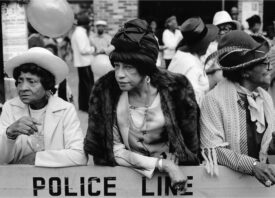

“You also have the protests that Jim documented and in that, he photographed a Women’s March in 1965, protests march for against the Vietnam War, Free Speech, racial equality — all of those were in those marches and rallies. I think today’s generation, with what’s going on politically, feel really helpless. I’m hoping they will look at these peaceful protests and maybe gain some strength and say, ‘We can do something. We can make a difference through peaceful protest and speaking out.’ I think that’s what Jim’s photographs do: inspire a whole new generation of activists or even musicians and writers, to inspire them to bring that into this time period.”

Can you speak about what it was about music in its many forms that spoke to Jim as an artist, and how he sought to capture and translate that art from one form to another?

“The words and the music are so meaningful — they tell a story and then Jim tells the story through his photography. They all exist together in harmony and Jim was able to capture that. The musicians don’t even know he is there so he is truly capturing that moment that you can’t recreate, especially with jazz where they can play the same song three days at a festival and each time it’s going to be different because it’s all based on your feeling at that moment. That’s what Jim was able to catch: that fleeting emotion and feeling in that moment. He was so good at that because he wasn’t intrusive. What’s great about the Leica is it is quiet. It’s not this huge camera so he was able to capture that.”

Jimmy Rushing backstage at the Hunt Club, Monterey Jazz Festival, Monterey, California, 1960

Can you share how musicians responded to Jim and the way in which they collaborated in the creation of these works?

“Because Jim befriended a lot of musicians, their guard was down because they knew Jim would never take a bad picture of them. Some of them were in compromising situations where they would be doing drugs and they knew Jim would never betray that trust and show one of those photographs he was trusted by them because they knew he would take a photograph and would pick the one that would represent them in a non-compromising situation even though he was there.

“A great example is the Rolling Stones, the 1972 tour. That was the cocaine tour basically, but Jim never published any of those. He photographed this larger than life band on stage but then you go backstage where Mick Jagger is doing yoga on the floor. He caught these iconic figures yet he was able to bring them down to humanity and show them as human beings also. He was able to show the many different sides, especially the human side of these musicians and activists, and show their quiet moments. They are not just larger than life figures. They feel. They’re sad, happy, the whole range of who the person is.”

What did Jim consider to be his most important contribution to history?

“I think it was representing the disenfranchised, the Black musicians were so important to him to portray and show because their music was so soulful and universal. Not only did Blacks listen to it and feel it, but whites could and try to understand some of their struggle.

“I think it was important to Jim to represent people that would not be mainstream. He went into Hazard, Kentucky, and photographed a coal mining family there. You feel them in these shacks made out of cardboard but you don’t feel sorry for them. You feel their pride. They don’t want to be portrayed as poor ‘poor people.’ Jim wanted to be honest about his photography and was able to convey these feelings to the viewer. Whatever it was, he thought it was important to share that and he did that through his story telling in photography.”

Jimi Hendrix during his sound check, Monterey Pop Festival, Monterey, California, 1967

Odetta and Elizabeth Cotten, joyful at the rare opportunity to see each other backstage at the Berkeley Folk Festival in 1978. The great Odetta, a.k.a. “The Voice of the Civil Rights Movement,” is cited as the key inspiration in the folk revival of the 1950s and 1960s. She was also a major influence for Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Janis Joplin, and Mavis Staples. Elizabeth Cotten wrote “Freight Train,” honed the left-handed guitar style known as “cotten picking” and never played anywhere but in church until she was in her sixties, when she was discovered by the Seeger family, for whom she worked as a housekeeper.

Miriam Makeba, night club in New York, 1960. Born in South Africa and known as “Mama Africa,” Makeba popularized African music in the United States and globally. She campaigned against apartheid feverishly, for which her citizenship and right to return to her home were revoked. She returned in 1990, after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison.

All images: From Jim Marshall: Show Me the Picture by Amelia Davis, published by Chronicle Books 2019 © The Estate of Jim Marshall