Search this site

War Veterans Who Have Found Peace and Healing in Vietnam

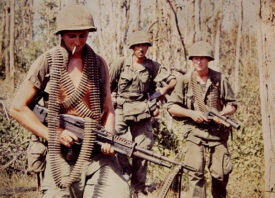

On July 21, 1954, Vietnam was split, the fractured nation a pawn of the Cold War. The communist North and the capitalist South became pitted against each other in a twenty-year war that would destroy not only the Vietnamese people and their land but countless foreign soldiers sent to fight a brutal proxy war.

The United States entered into the conflict in 1964 after the suspicious Gulf of Tonkin incident, and for the next nine years drafted American men, disproportionately from working class, Black, and Latinx backgrounds, to fight a war they could never win.

That did not stop the U.S. military from engaging in some of the most heinous acts of war, from the My Lai Massacre in 1968, wherein their gang raped women, mutilated children as young as 12, and slaughtered some 504 innocent villagers uninvolved in the conflict.

Reportage of the war was as brutal as the acts themselves, fomenting a righteous ant0war favor stateside. Public sentiment split the nation in half, with warmongers deriding anti-war protesters and eventually spurring on the National Guard shooting that left four U.S. students dead during at Kent State in Ohio in 1971.

When Vietnam veterans returned home, they were discarded writ large by both the public, that saw them as villains, and by the government, which offered them little medical treatment or financial support. Public sentiment was further fueled by a series of Hollywood films like Apocalypse Now, Platoon, Full Metal Jacket, and Born on the Fourth of July, that struggled to make sense of the horror and hell that American soldiers experienced in Vietnam.

Then suddenly, the conversation stopped altogether. No one spoke of the war or the veterans anymore. Vietnam rebuilt and became a tourist destination, Westerners marveling with wonder and awe. But beneath the surface, a darker truth remained. Those who survived the war are living with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) for decades.

“According to a study by the Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, the number of US veterans who fought in the Vietnam War and committed suicide is higher than the number of fallen American soldiers during the Vietnam War itself,” Rebecca Rütten reveals in the artist statement accompanying In Vietnam I Found Peace, a series of photographs and interviews with American and North Vietnamese veterans living today in Vietnam.

“Only by being exposed daily to the place where all the suffering had started, could they deal with their trauma and attempt to overcome it,” Rütten explains. Here, she speaks with us about her experiences making this powerful body of work, exploring the lives of men living with a silent killer as they continue to fight the Vietnam War.

What inspired you to create this body of work?

“When I was traveling South East Asia in 2016, I started my research into Vietnam on Reddit. Here, I came across a post by Michael Hasford, a former Vietnam War veteran from America. His post titled, ‘The Only Vietnam Story I’ve Never Told…’ described in great detail his horrific experiences of being a teenage soldier in a war far away from home, and how he was forced to keep quiet about the terrible things he went through.

“His story made me curious to learn more. On a Facebook Group for American War Veterans I got the contact for a former GI called Larry who was then traveling in Vietnam and he agreed to meet me in a Café in Ho Chi Minh. Larry showed up with his American Vietnam War veteran friend Bill and invited me to ask anything I wanted to know.

“That was the first time I learned about post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and that for some veterans the only way to deal with their trauma, was not only returning but completely moving to Vietnam. Apparently, only through daily exposure to the place where all the suffering had started, could the men deal with their trauma and attempt to overcome it. Today, these veterans call Vietnam their home – not the United States.

“This story fascinated me so much, that the following day I bought a Motorbike for $200 and started riding more than 1.500km from Ho Chi Minh City to Hanoi. On my way up north, I stopped in several places to talk with as many American veterans as I could find about history and healing. After this trip, the stories were still stuck in my head and a year later I returned to Vietnam with the mission to create this body of work.

How did you connect with the former American soldiers who had moved to Vietnam, and how did they respond to your inquiry to photograph them and share their stories?

“On the first trip the Veterans I encountered were through recommendations from Bill and Larry. Later, one guy led me to another. When I returned to Vietnam a second time, I focused on the characters that in my eyes contributed the most to rebuilding the country and community support. Bill, Chuck, David and Hung were the most exciting and charismatic men and they were very open to participate in my project on all levels.”

What aspects of PTSD do you want to explore with this work?

“What most Veterans I met during my trip had in common was a mental illness labeled PTSD. The Veteran David Clark stated, ‘When I’m in the US, the Vietnam War haunts me day and night. In Vietnam, strange as it may sound, I have found peace. Only on anniversaries of the war, when friends die or when I get sick, then all the grief and horror suddenly come back. It’s like trying to find a space at a parking lot, but there is none. The parking lot is your head, the circles of the car are the terrible thoughts that never stop. That’s how I would describe post-traumatic stress disorder.’

“While working on this project I learned that the number of US veterans who fought in the Vietnam War and committed suicide is higher than the number of fallen American soldiers during the Vietnam War itself.

“Different from many other American veterans Bill, Chuck, David, had found a way of dealing with the past. Continuously they experience how much the Vietnamese community has forgiven and respects elderly members of the community. By being exposed on the daily to the fact that the nightmares of the past are over, this way the veterans are reminded that they can continue their lives in peace. Additionally engaging in war relief projects on a regular basis helps the men further move on from their guilt.”

How does photography as a medium lend itself to the conversation?

“Many of the Americans that have returned to Vietnam are living in a state in-between the horrific past and the relieving present. I wanted to make this internal split visible by splitting the closely framed faces of the men with the colors red and blue. A

“Also the ritual of taking the portrait became important. I asked the veterans to close their eyes and remember a significant moment of the past that changed everything for them. Often I waited up to five minutes until I had the feeling something in their faces changed, only then I pressed the trigger and took the portrait. This is how I wanted to make mental health issues that cannot be seen, visible and shine a new light on an old story.”

How does the experience of talking about PTSD impact the subjects while they are sharing their memories, as well as afterwards?

“It was important for me to tell the men that they were completely free to drop out of our conversation at any moment during the interviews, in case I might trigger their PTSD. For them sharing memories and visiting places, was a positive experience, because they felt heard and seen.”

How did you find Nguyen Ngoc Hung, and what was it like to hear the story of the Vietnam War from his perspective?

“When discussing the missing Vietnamese perspective in my project with the veteran Chuck, he guided me to an old friend of his called Nguyen Ngoc Hung. Hung used to fight as a North Vietnamese soldier during the war against the Americans. In the 90’s Hung was even invited to the United States to give lectures to the US veterans.

“In our interview Hung said, ‘At first, it was difficult for me to meet US veterans and tell them my story. But later I heard from them that my experiences were very similar to theirs. Friends who died and who they had to bury them during the ongoing operation. For the first time, we met as humans.’

“Although his body is covered with scars from the battlefield, Hung points out that he could have never moved on from the past if he had not forgiven the Americans for everything that had happened. He is happy that they returned.”

How does this exploration of war and lifelong PTSD inform the time we live in today, when the United States remains in Afghanistan, making it our longest war ever? What would you like people to take away from their encounter with your work?

“During my stay in Vietnam I not only met American veterans of the Vietnam War, but also those of Iraq and Afghanistan. I found it abstract that all veterans suffered a similar pain, although they were different generations.

“Vietnam has welcomed the Americans back to work on the rebuilding and healing of the country. This act of forgiveness had a healing effect for many American veterans of the Vietnam War, and made veterans of other wars wonder if they too could someday go back to the countries they once fought in and do the same that is being done in Vietnam. Seeing how others find closure to the legacy of war, is very encouraging and gives hope.

“We should have learned much more from the Vietnam War than we did. We need to change our policy on how we view the world and learn about the mistakes of others and meet with other cultures with understanding, instead of fighting them.”

All images: © Rebecca Rütten