Search this site

Rediscovering “The Hampton Album,” a Renowned Record of African-American History After the Civil War

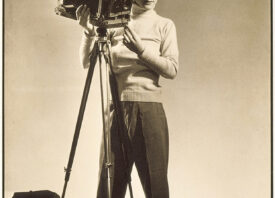

Credited as the first female photojournalist in the United States, Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864-1952) received a commission in 1899 to photograph the Hampton Institute, a private historically Black university located in Hampton, Virginia.

Founded in 1868, just four years after the Civil War, the Hampton Institute was dedicated to the education of African-American men and women — and from 1878 to 1923, also maintained a program for Native Americans. The campus was located on the grounds of “Little Scotland,” a former plantation. Among its many illustrious alumni was no less than Booker T. Washington who taught at Hampton after he graduated before going on to found Tuskegee University.

Over the course of several weeks in December 1899 and January 1900, Johnston created a series of work that came to be known as the Hampton Album, a series of 159 luxurious platinum plates offering a window into daily life for Hampton students. Displayed in a cabinet with folding leaves, the work was first exhibited in the American Negro Exhibit at the Exposition Universelle in Paris as part of the U.S. government’s efforts to rebrand its international image following the decimation of the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Johnston’s photographs were designed to illustrate Hampton’s educational philosophy of vocational training in order to achieve economic advancement — a practice that W.E.B. DuBois argued was far too limited a vision for the newly-liberated yet systematically disenfranchised group.

Johnston’s photographs reveal the tension between ambition and assimilation that has long defined the place of everyone “othered” in American life — the misguided belief of exceptionalism that posits if you pull yourself up by your bootstraps, you can climb the ladder to success. As the first female photojournalist, Johnston may have understood this mission better than most.

“Without a doubt Frances Benjamin Johnston was photographing the students at Hampton Institute with real integrity,” writes LaToya Ruby Frazier in the essay for the book titled “Photographs, Schools, and Systems. “There’s no malice or judgment against the assignment or the subject. It’s commendable that she accepted the commission and took the time to make these portraits with as much dignity and humanity as possible for the subjects themselves.”

This dignity gives the photographs a sense of importance and weight, offering a depiction of the speed of progress made by Black Americans in the years following the Civil War. Ready, willing, and able to contribute to the community and the cause, the young men and women pictured in Johnston’s photographs underscore the immense potential residing in the first generation born after slavery.

At the Exposition Universelle in Paris, the American Negro Exhibit was awarded Grand Prix, as well as a dozen other medals and honorable mentions. But the progress of the era, like the photographs themselves, disappeared as the Ku Klux Klan rose to power, supported by the Woodrow Wilson White House.

The album wasn’t resdiscovered until some time during World War II when Lincoln Kirstein found it in a Washington DC bookstore; he later donated to the Museum of Modern Art in 1965. A year later, the photographs finally returned to public view, during the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

Now, over half a century later, they have reemerged in this beautifully composed book, which provides a poignant look into the past and a potent reminder of the power that resides in Black America then — and now. Here Sarah Hermanson Meister, Curator, and Jane Pierce, Carl Jacobs Foundation Research Assistant, share their insights into the story of The Hampton Album, which was just published by the Museum of Modern Art.

What inspired you to unearth the Hampton Album more than 50 years after the work was first exhibited and publish it as a book?

“The Museum is always looking for opportunities to share unique objects in the collection, and we had long identified the Hampton Album as a priority. An opportunity arose when our colleagues were organizing an exhibition around the legacy of arts impresario Lincoln Kirstein, who discovered the Hampton Album during World War II and gifted it to the Museum in 1965. We were thrilled to be able to publish all of the images for the first time, alongside many new research discoveries.”

Could you speak about the significance of this body of work in the world today, and what it brings to the conversation of photography and the history of Black America that may have been otherwise overlooked, ignored, or misrepresented?

“This is a challenging and important question. One partial answer might be addressed by considering LaToya Ruby Frazier’s contribution ‘Photographs, Schools, and Systems.’ Johnston’s visual record of this historic educational model opens a window to different types of contemporary conversations, including ones anchored in politics of representation and bias in the educational system today. Frasier observed, ‘I’m indebted to a woman I’ll never meet, whose work nevertheless remains a powerful springboard for tackling what we think education is today—and how we need to radically change it.’”

Could you speak about the significance of Frances Benjamin Johnston working as a photographer during the first wave of women’s liberation in the United States, and how her independence informed the way she managed her commissions?

“Johnston was certainly a pioneer for women in the field of photography: in 1897 she published an article in Ladies Home Journal explaining how other women could maximize their success in the field. This confident, ambitious attitude led to her being invited to organize an exhibition of American women photographers at the 1900 Paris Exposition.

“It’s remarkable how Johnston managed a successful commercial business and maintained her own distinctive style throughout. Johnston worked on multiple commissions of educational systems, including the Washington, D.C., public school system (spring 1899), Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (December 1899 and January 1900), the Carlisle Indian Industrial Institute (March 1901), and Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (1902 and 1906). The photographs are notable for their taut compositions and delicate quality of light, as well as for their attentive sympathy toward her subjects.”

Could you speak about the significance of this period in Black American history, in the years between Reconstruction and Jim Crow, honing in on institutions like Hampton?

“This was an incredibly complex time in American history and, as art historians, we have to acknowledge that our understanding of this period is a relatively narrow view of what other historians have studied and analyzed with a much broader perspective. The book addresses historically specific commonalities between Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois, and then traces the shift in thinking away from a predominantly vocational model in favor of a broader academic one — a shift mirrored in the transformation of Hampton to a university.”

Could you speak about the reception the work received when it was first shown at the American Negro Exhibit at the 1900 Paris Exposition?

The exhibit was received with great fanfare in 1900. It was awarded dozens of prizes, including the most prestigious Grand Prix. Popular response was so positive that arrangements were made to have the exhibit travel to Buffalo and Charleston after its run in Paris.

“In an essay published in the American Monthly Review of Reviews, Du Bois captured the exhibit’s success: ‘We have thus, it may be seen, an honest, straightforward exhibit of a small nation of people, picturing their life and development without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves. In a way this marks an era in the history of the Negroes of America. It is no new thing for a group of people to accomplish much under the help and guidance of a stronger group. . . . When, however, the inevitable question arises, What are these guided groups doing for themselves? There is in the whole building no more encouraging answer than that given by the American negroes, who are here shown to be studying, examining, and thinking of their own progress and prospects.’”

Could you share the response to the work when it was rediscovered and shown at The Museum of Modern Art in 1966, just as the Civil Rights Movement was reaching extraordinary new heights?

“Admittedly, the Museum could have done more to address the Civil Rights Movement and other contemporary circumstances in the mid-1960s. Kirstein, who wrote the foreword to the 1966 publication, acknowledged the album’s complexity while privileging an artistic consideration: ‘It is more than likely that social and historical factors outweigh purely aesthetic values in Miss Johnston’s plates, but here, upon the limited wall-space of a museum and within the few pages of this brochure, let us, primarily, discover these pictures. They are amazingly evocative.’

“A handful of contemporaneous reviews address the political environment. We quote a few of these in the book, but the most extensive concludes: ‘If all of this seems dated and much of it pathetic, if we see Frances Johnston’s photographs differently from the way she saw them, we must still ask the question: Was there any other way in 1900?’”

All images: Frances Benjamin Johnston, from The Hampton Album, courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.