Search this site

Arlene Gottfried’s Mesmerizing Photographs of New York in the 1980s

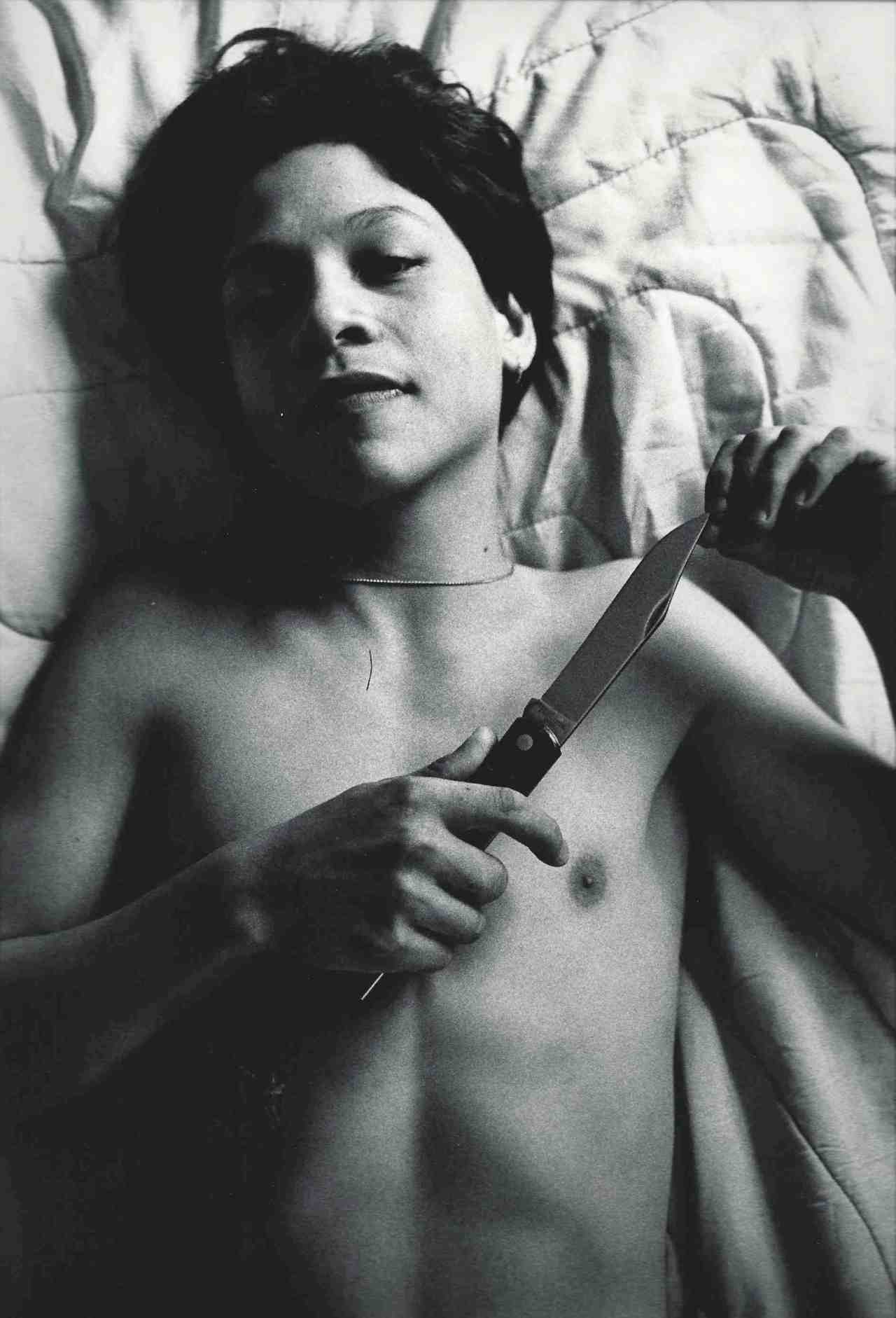

Boy with Knife, late 1970s

Heroin Series, Man With Beer And Cigarette, late 1970s

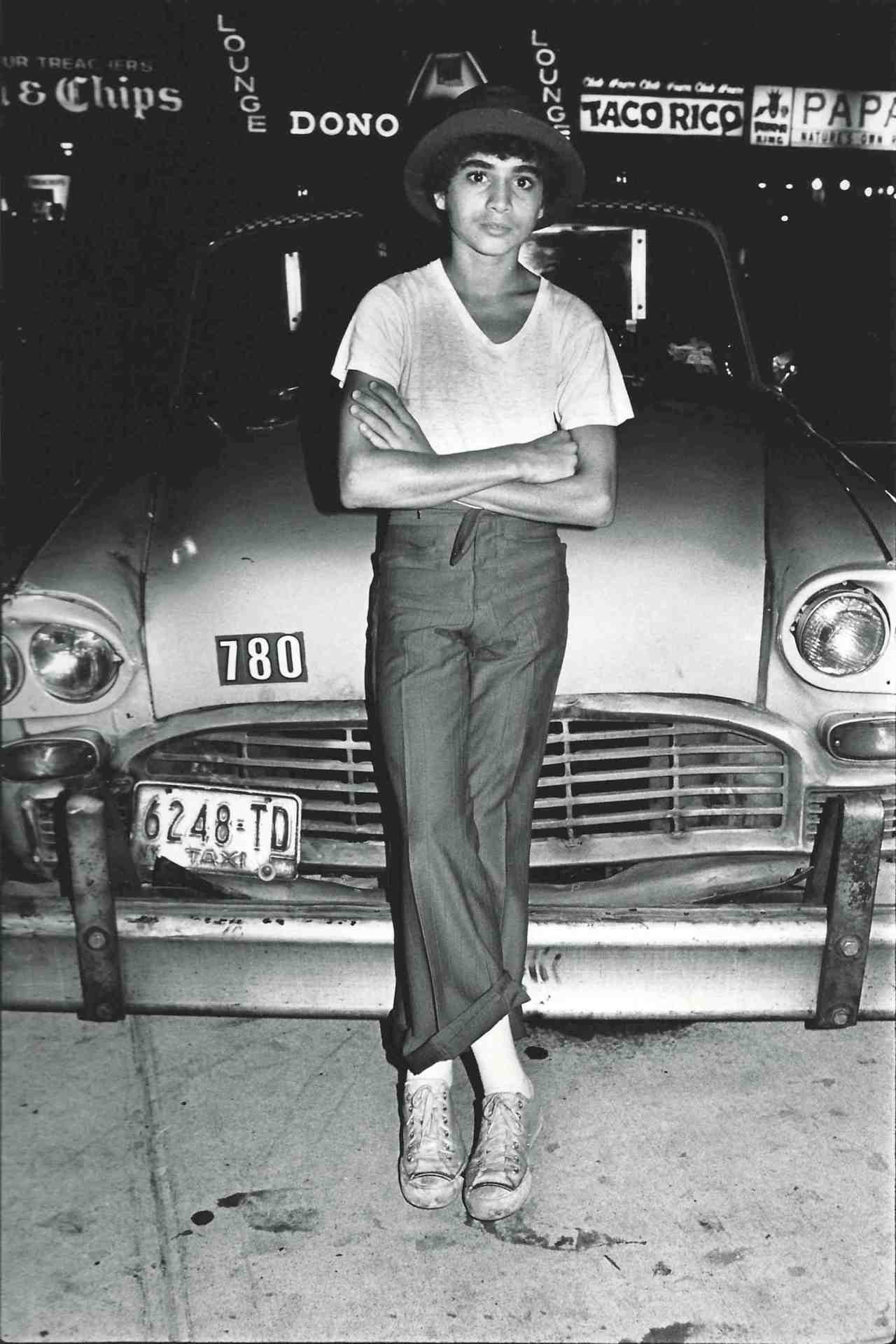

Hailing from Coney Island, Arlene Gottfried (1950-2017) grew up on the streets of Crown Heights during the 1960s just as white flight was reshaping the face of New York. She moved to Greenwich Village in 1972 as a young photography student enrolled at Fashion Institute of Technology and soon thereafter her family moved to the East Village when it was more familiarly known as Alphabet City — one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Manhattan.

But the ragged, jagged edges of the city didn’t frighten Gottfried. Rather, like a moth to the flame she found herself drawn to the people living on the margins, whose lives often fell between the cracks, and made it her business to create some of the most sensitive, compelling portraits of an era that has all but vanished.

“New York City street photography is genre of photography itself. How many photographs of New York have been made?” gallerist Daniel Cooney asks. “What makes Arlene’s work special is Arlene herself. We see New York as Arlene sees it. It is not the subject matter, because the subject matter is not new. It is Arlene. She was an original.”

Cooney organized Arlene Gottfried: After Dark, which was recently on view at the gallery, spotlighting the artist’s work made in some of the most legendary outposts of the late 1970s and early ‘80s. Whether hanging out at Studio 54, cruising through Times Square, kicking it at Empire Roller Disco, lounging in the ladies room at the Roseland Ballroom, or walking down Christopher Street during Gay Pride, Gottfried captures the beauty of people who persevere against the odds, defying state-sponsored oppression by simply remaining alive.

Included in the exhibition is a series of never-before-seen photographs of heroin users that reveals the opioid crisis of the era, which was received quite differently from the times in which we now live. The people in Gottfried’s photographs are largely Black, Latinx, and poor — early fodder for a burgeoning prison industrial complex started by former President Nixon that would boom under Reagan’s regime. In her portraits, we see those who have sought to escape the trauma of their lives through IV drugs, just as AIDS was taking shape, ready to wipe an entire generation out.

Gottfried’s photographs did what few of the era had done: she made the political personal. Rather than play into dominant narratives criminalizing drug users, she humanized them, showing us their pain and their dignity in equal part. “I think the Heroin series is very important in the oeuvre of Arlene’s work,” Cooney says. “It shows that Arlene was tougher than her demeanor might suggest. It also reveals that Arlene always looked her subject’s in the eye no matter the situation.”

Gottfried maintained this gaze with everyone she encountered, no matter when or where she crossed their path. Her eye was an extension of her heart, her finger on the pulse, always able to transcend the boundaries that keep us apart, isolated, and cold. She possessed a profound sense of empathy that allowed her to get close, to be in a moment of intense emotion and vulnerability, to find a moment of repose in her encounters that acknowledges and understands, honors and respects, cherishes and loves.

In her photographs we see Gottfried in the eyes of those she met, a woman who understood that the photographs will outlive us all. Hers is a world that few knew unless they were there, and in her work we are given a moment to examine just what we think we know about those who are trying to survive by any means necessary.

72nd Street, late 1970s

Woman at Lounge, late 1970s

Chi Chi Valenti and Johnny Dynel, 1982

Woman In Front Of Topless Bar, late 1970s

Pete’s Sister In Law, 1981

All images: © Arlene Gottfried, courtesy of Daniel Cooney Fine Art.