Search this site

Exploring the Nuances of Nigerian Identity and the Performance of Gender

UNTITLED III, 2019 Archival Ink Jet Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag 130 x 90 CM

I MISS YOU, 2015 Archival Ink Jet Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag 119 X 79.5 CM

UNTITLED IV, 2019 Archival Ink Jet Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag 70 x 46.67 CM

For imperialism to succeed and persist, it must other everything that it is not in order to justify injustice and sin. At its disposal are tools like ignorance, arrogance, disinformation, indoctrination, frailty, and fear — all of which can be used to foment the ugliest emotions of the weak-minded, impotent, and malicious people willing to stand behind a political structure that would just as soon turn on them.

When we consider representations of Africa, they’ve long been filtered through the lens of a colonial agenda that has exploited the people and the land to diminish the massive contributions of Black peoples to world civilization for tens of thousands of years. This othering, which condones slavery, racism, and oppression in the name of religion, has systematically stripped the humanity from all who come into contact with it.

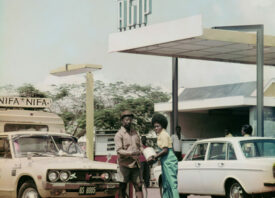

But art has the power to change how we see and think about the world, providing perspectives created from inside looking out and reflecting upon the deeper truths about the nature of life and the human condition. In his work Nigerian artist Lakin Ogunbanwo centers the experiences of different ethnic groups from his homeland in the series e wá wo mi and Are We Good Enough, recently on view at Niki Cryan Gallery. Ogunbanwo’s works document the complexities of his culture to resist the West’s monolithic narrative of Africa that reduces 54 countries on the continent into a single identity.

E wá wo mi (“come look at me”) explores the subject of Yoruba, Igbo, and Hausa-Fulani brides and the performative aspects of gender in relationship to marriage ceremonies. For many women, weddings are complex webs weaving together ideas of love, family, and identity as they play the roles of wife, mother, and daughter-in-law. Issues of submission, fertility, and support come to the fore, and within their respective cultures they are required to perform these as the pinnacle of the feminine ideal.

While each woman dons a veil to make them somewhat interchangeable, each bears an element of costume emblematic of her tribe: the Yoruba woman wears a headscarf known as a gele, the Hausa-Fulani has henna-painted hands, and the Igbo woman wears ivory bracelets and a coral beaded cap and necklace. Each woman is lit so that her dress is the focal point, further underscoring the performative aspect of the ceremonial moment.

The series stands as a stunning counterpoint to Ogunbanwo’s ongoing project, Are We Good Enough, begun in 2012. In this series, the documents hats worn as cultural signifiers by various ethnic groups in Nigeria, photographed from the back so as to obscure and protect the identity of his sitters. As with the brides, Ogunbanwo focuses on the marking of the larger cultural collective, using the hat as “that witty but vital accessory in fashion” to speak of masculine identity.

Taken together, both series offer a portrait of the people as seen by an insider who understand not only the symbolic importance of adornment but the ways in which gender informs and influences one’s sense of self.

UNCOVER, 2015 Archival Ink Jet Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag 119 X 79.5 CM

UNTITLED V, 2019 Archival Ink Jet Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag 70 x 46.67 CM

I WAS GONNA CANCEL, 2015 Archival Ink Jet Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag 119 X 79.5 CM

UNTITLED VII, 2019 Archival Ink Jet Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag 70 x 46.67 CM

LET IT BE, 2016 Archival Ink Jet Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag 119 X 79.5 CM

All images: © Lakin Ogunbanwo