Search this site

Seeing the Unseen in the Groundbreaking Work of Harold Edgerton

Milk drop coronet, 1957

Bullet through apple, 1964

Cranberry juice dropping into milk, 1964

Engineer, educator, explorer and entrepreneur, Harold E. “Doc” Edgerton (1903–90) was also a groundbreaking photographer who revolutionized the medium when he developed the first electronic flash, or stroboscopic light, which revealed motions in segments unseen by the human eye in 1931.

Described as “an American original,” by former student and Life photographer Gjon Mili, Edgerton was a visionary, fusing the divide between art and science while working at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Understanding his work would be best understood by making it relatable to the lay person, Edgerton made action-stop images of machines, animals, and athletes to illustrate just what his invention could do — even going so far as to show a bullet fired through an apple. You might even say, he knew his audience better than they knew themselves.

Harold Edgerton: Seeing the Unseen (Steidl) is a beautifully illustrated compendium of the innovator’s work, bringing together more than 100 of his most important images, along with excerpts from Edgerton’s laboratory notebooks. Taken as a whole Edgerton’s work illustrates just how deeply his work has seeped into cultural consciousness, as we take these “special effects” for granted, not realizing the debt we owe not only to science, but to the possibilities of photography.

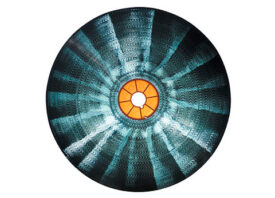

The book’s cover image, Milk Drop Coronet, was recently named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential photographs of all time, with the caption explaining, “The picture proved that photography could advance human understanding of the physical world, and the technology Edgerton used to take it laud the foundation for the modern electronic flash.”

As Gary Van Zante writes in the book, “The early reception of Edgerton’s work was similarly auspicious, y a time when photography was struggling to be recognized as an art form , and development of institutional and private collections of photography was in its infancy. In 1933, Edgerton’s milk splashes appeared in the Royal Photographic Society’s annual exhibition, and he continued to show work there regularly into the next decade.”

This platform immediately elevated Edgerton’s work in the realms of fine art. Edgerton, however, was nonplussed, declaring, “Don’t make me out to be an artist. I am an engineer. I am after the facts, only the facts.” Nevertheless, the aesthetic, formal, and transformative properties of the work cannot be denied; whether he intended it or nor, the photographs are beautifully rendered images of an idea that is both instantly recognizable and flawlessly composed, often delving into the realm of abstraction to reveal a fluidity between representational and symbolic iconography.

At the same time, Edgerton’s work is highly cinematic, revealing the ability to show motion and the passage of time in a medium that suggests otherwise. Even within a fraction of a second, an entire universe exists, one that lies far beyond our perceptual powers and requires the external aids to be understood.

It’s a telling reminder that the empiricism, as a system of knowledge and understanding, is simply not enough. Edgerton’s work reminds us that our natural capabilities are limited by the assumption that nothing exists beyond them unless we dream of finding the tools to bring imagination to life. It is here, in his photographs that we can dream of seeing the unseen.

Gussie Moran, 1949

Diver (Charles Batterman), 1955

Water flowing from a faucet, 1932

All images: © 2010 MIT. Courtesy of MIT Museum, book published by Steidl.