Search this site

Nick Brandt’s Devastating Portrait of Africa on the Brink of a Perilous New World

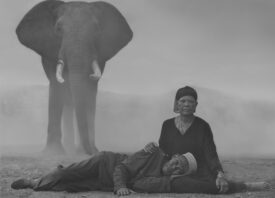

Known for his intimate photographs of animals set among sweeping vistas of East Africa, Nick Brandt has spent his career responding to the fragile ecosystems, creating captivating portraits of life on the brink of a perilous new world.

Brandt began observing changes writ large to Africa’s national parks and surrounding areas and used his photography to respond to the rapid transformation of the landscape and its impact on the natural world. Between 2014 and 2015, Brandt created Inherit the Dust, a series of unreleased portraits of animals made in years prior that were then printed life-size, glued on panels, and placed in areas of African where they once roamed but no longer do as urban development is moving at an explosive pace.

The photographs from Inherit the Dust will be on view in Nick Brandt: Inherit the Dust at Blue Lotus Gallery in Hong Kong from March 13–April 22, 2020, and will be coming to Fotografiska New York in 2020. His works offer a haunting look at the changing landscape and its impact on both the majestic creatures that once roamed free as well as the impact of industrialization on the people who live in these areas.

Species including rhinoceroses and pangolins are on the brink of extinction due to poachers who slaughter them en masse for a black market that feeds a limitless appetite for luxury objects, delicacies or medicines. Despite the international bans wildlife crime has become the fourth most profitable illicit trade in the world (after guns, drugs, and human trafficking), with profits estimated at US$19 billion each year. Hong Kong is currently the biggest hub for ivory and wildlife trade — making this exhibition a salient reminder that there is far more at stake with the needless slaughter of wildlife.

Here Brandt shares his journey and wisdom so that we may all be aware that if we do not stop the senseless killing, the beauty of the earth shall perish — never to return.

How did you conceive of the concept for Inherit the Dust?

“Over the years of time spent in East Africa, I’ve driven through countless areas where just ten years ago there was animal life, but now has been relentlessly wiped out — sliced up and reduced to bush meat, leaving vast expanses of land devoid of any large mammals.

“That sudden absence, that systematic annihilation of what was once there, was part of the reason for the conception for the project. The same concept could also have been applied to any number of places in the world. East Africa just happens to be where I had photographed up until then, and about which I know most.

“It’s taken billions of years to reach a place of such wondrous diversity, and then in just a few shockingly short years, an infinitesimal moment in time, to annihilate that.

“And mainly, it’s about all of us. Significantly, it’s about the terrifying number of us, and the impact of the very finite amount of space and resources for so many humans.

“So all of this was the genesis for Inherit the Dust.”

Could you speak about the process for determining the choice of animal portrait and the location it was erected?

“Before I started scouting for locations, I had searched through hundreds of old contact sheets spanning a number of years for photos that, for one reason or another, had never been released as limited edition prints.

“A group of 30 photos were ultimately selected as options, and printed in strips that once glued together, would be life-size match prints of the animals.

“Once locations were chosen, I attempted to match the animals that felt most emotionally resonant within the setting, as long as animals such as these had indeed once roamed there.

“However, a critical component was that the horizon lines in the original photos had to perfectly match up with the horizon lines in the locations in which the photos were to be set.

“So for example, it took months to find a set of hills in the background that perfectly matched the contours of the hills in Wasteland with Rhinos. Eventually, by complete happenstance, I did. I think the match is uncanny.”

Could you share some of the challenges in executing a project of this scope?

“Aside from matching the horizon lines between original photograph and location, the biggest challenge was financial — the amount of money I spent on crew members standing around on location day after day waiting for clouds to appear in the sky.

“Even if photographing in East Africa, I like my clouds – and the light that they create — looking like they were imported from northern Europe. Clouds that are somber and melancholic.

“Even in the rainy season, it’s still East Africa. Which means a lot of sunshine. So there was also a lot of waiting for the right cloud.

“Obviously, any scene is instantly transformed in terms of look, mood and emotion by the sky overhead and accompanying light. None of these panoramas would have worked bathed in hard sunlight. The melancholic atmosphere that I sought for this body of work would have instantly vanished.”

How were the works received by the local communities during the creation of the photographs, and afterwards?

“Most of the people, struggling to survive on a daily basis, had far more important things to think about than some crazy white guy putting giant photos of elephants up in the middle of the landscape.

“Which gets to the more important point — that the people in most of these photos are also victims of environmental degradation. Environmental degradation will almost always affect poor rural people the most, due to the exhausted natural resources upon which they rely.”

Could you speak about the challenges facing African nations industrializing today, and the conflicts that arise as a result of these massive changes to the environment?

“Most African people would say that our Western societies trampled all over our own natural world centuries ago in the interests of economic expansion, and that in Africa, they never got much of a chance to develop economically until now.

“And so now it is their turn to economically grow. Why should they be deprived of the comfortable, material lives that we have in the West? In some regards, it’s a reasonable argument.

“But protection of the environment and economic benefit do not have to be mutually exclusive. In fact, they can go hand in hand.

“For example, in the area in Kenya – poor, but teeming with natural wonders – in which Big Life Foundation, the non-profit I co-founded, operates, nature tourism and conservation are the only real source of long-term economic benefit. Take away the animals, and there’s almost nothing left of economic value as the arid land becomes more and more overgrazed.

“Meanwhile, when an elephant is killed by poachers, the average sum earned by poachers and traffickers has been estimated at less than US $20,000 (probably much lower now), with none of it seen by the community. But it’s been calculated that over the course of its lifetime, a single elephant will contribute more than US $1.6 million to the local tourism economy.

“So Africa is sitting on a goldmine — well, an elephant mine. And as the continent-wide destruction continues, those ecosystems and animals that remain will become even more highly valued.”

All images: © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Blue Lotus Gallery