Search this site

The Artist Who Escaped New York’s COVID-19 Pandemic Without Leaving Home

When the COVID-19 crisis first hit the United States, New York City became the epicenter for the pandemic. By April 1, a harrowing 5,000 cases were reported every day, forcing the city to shut down en masse. While unrooted transplants and the uber rich fled en masse, spreading the virus across the United States, New Yorkers of all stripes hunkered down to weather through the storm.

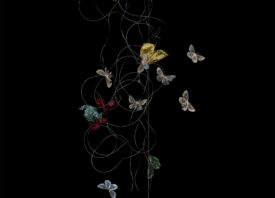

For many the feelings of isolation, on top of the specter of illness, death, unemployment, housing and food insecurity have been devastating. Forced to adapt to extreme circumstances, many dug deep into themselves, looking for ways to make the best out of a bad situation. Artist Karine Laval found solace in the terrace garden of her Brooklyn home, where she began making photographs collected in The Great Escape, now on view by appointment in her Brooklyn garden through September 7 as well as via an online video tour.

“Our only escape and way to cope with a feeling of imprisonment and anxiety may be to make best use of what we’re lucky to have and use the power of our imagination to push back the limits of our own confinement,” Laval says. Here she shares her journey to align with the progress of nature itself, finding solace and inspiration to create by following the organic cycle of life and death.

To begin, can you tell us about how your life has changed living in Brooklyn during the COVID-19 crisis?

“I started to self-quarantine on March 5 upon my return from a trip in Costa Rica. While there, I was loosely following the news and receiving messages from my family in Europe, describing how COVID-19 was raging and countries were shutting down. The US still seemed to be in a bubble of their own but I had no doubt that we were not going to be spared. I decided not to take public transportation anymore, avoid seeing anybody and stay inside unless I needed to go out to shop for food.

“I’ve followed that routine until the end of June, and I’m still social distancing. I don’t think I’ve ever been in the same place for that long during my entire adult life. I’m usually very social, and love to host dinners for friends and visit my family in France and Germany a few times a year so i’s been a big change of rhythm. I also travel a lot for work, whether it’s for an assignment or commission or for my own personal work.

“This forced pause has also affected my professional life. Luckily, I was working on a large-scale installation project in London when the lockdown started here and there, but we’ve been able to continue to work on it remotely despite major delays and hurdles.”

Could you share some of the life lessons you have learned having had to adapt to life in New York when it became the center of the global pandemic?

“This extraordinary experience has made me appreciate time, space and the ordinary in new ways. It also helped me enjoy and focus on the simple things that immediately surround me, like my own garden, my home and my neighbors. It’s not that I was not paying attention to them before, but my awareness and enjoyment of them all was definitely enhanced.”

Can you tell us about your experiences tending to your terrace garden and what you observed about being so closely involved in the process of nature?

“I feel fortunate to have a terrace and a small garden, where I’m spending time whenever the weather permits. I’ve never had the opportunity to see spring unfold the way it did this year. Flowers and bushes came to life in slow motion and I’ve watched nature follow its course while our lives have been on hold.

“There is an incredible variety of birds chirping and singing different melodies, which I hadn’t noticed as intensely as I’ve noticed this spring, certainly because the roar of the city had fanned away during the lockdown. Sometimes I even feel I’m transported into a tropical island or a rain forest, especially since New York is now considered a sub-tropical climate.”

What inspired you to begin thinking about making a series of photographs inspired by your garden?

“For the past decade, I have explored the notion of space as both a physical or geographical place—and also as a psychological and imaginary space that includes our relationship to nature and the environment we live in, between the natural and the artificial. After examining man-made places of leisure (i.e. swimming pools, beach resorts), I’ve become interested in another form of man-made environment: the garden.

“In 2014 I started the series Heterotopia, for which I traveled in the US and Europe to photograph public and private gardens. But I had never photographed for this series in my own garden. Being there everyday for weeks at a time, contemplating my own garden and witnessing its transformation inspired me to photograph it for my series Heterotopia.”

How have these new works may have been informed by the work you did for Heterotopia?

“I see this new work as a continuation of or a part of Heterotopia although it will always be a special capsule in time and space for me. I also use the same approach to produce the work. During this period of confinement and introspection, it also occurred to me that Heterotopia, and my work in general, had some connection with what we’re experiencing at the moment, being constrained into the limited realm of our homes.

“Although I usually get inspiration from the wider world and I’m away from my home while I work on a project, I often focus on contained and delineated spaces such as swimming pools or small areas in a garden, which I transform into fantastical larger-than-life landscapes that exist only beyond our perception and in the images I create. Somehow, through this new project my outer and inner worlds collapsed into one.”

Can you speak about how this experience inspired you to see your garden as an open-air studio?

“Instead of photographing these gardens in a straightforward, documentary tradition, I use the space of the garden as an open-air studio where I apply an experimental approach to create images rather than take photographs. The resulting pictures, which are far from a faithful portrayal of the plants and flowers I photograph, depict a disorienting representation of nature that can feel surreal or artificial. However, they are not derived from digital manipulation or post-production. The distortions, superimpositions and otherworldly colors are created in camera as single frames.”

How do you protect the prints from the weather elements?

“I’m not trying to protect the prints. They are casually pinned to the fences of the garden. They are printed on photographic paper and intentionally exposed to the weather. As a result they have been edited by rain, wind and sun, taking a life of their own. Just as we are at the mercy of nature and the virus, I decided to let go of control and let the works live on beyond me and be altered by the elements.

“I couldn’t afford this year to produce the exhibition at my regular printing studio, which was anyway closed. But I also thought it was fitted that the prints for the exhibition be produced ‘in-house’ with the only printer I have, which is a 17” wide Epson printer. In that sense, this is the ultimate ‘confinement’ exhibition of photographs of my own garden installed in that same garden a season later and produced within the limits of my home.”

All images: © Karine Laval