Search this site

The Magnificence of America’s Rivers, in Photos

“I have explored rivers on foot, canoe, raft, paddleboard, and car,” the photographer Ansley West Rivers tells me. “I have camped along their banks and swam in their waters.” She’s rafted the Grand Canyon sections of the Colorado River. On one occasion, she backpacked for three days through the John Muir Wilderness to reach the Tuolumne River.

“In these situations, I feel connected to so many of the early American landscape photographers, like Carleton Watkins and Eadweard Muybridge,” she admits. “But I have also shot sections that they would not recognize or know how to navigate.” Humankind has changed the landscape since those early days; today, some river sections are only accessible by car. According to a study released earlier this year, just 5% of U.S. river mileage is still considered blue, with color changes due, in part, to man-made climate change.

For West Rivers and her family, daily life has become inextricably linked to land and water. They own an organic farm, Canewater Farm, in the foothills of the Snake River Range, where they oversee four acres of mixed vegetables and flowers. In 2013, when she embarked on the Seven Rivers project, she set out to photograph the Colorado, Missouri, Mississippi, Columbia, Rio Grande, Tuolumne, Altamaha, and the Hudson Rivers during a time of profound change.

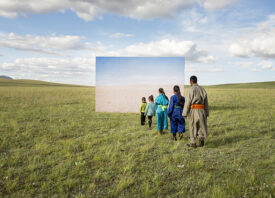

Like Watkins and Muybridge before her, West Rivers carries heavy gear through unpredictable terrain, relying on large-format film to immortalize her impressions of the land and moving water. She shares the pictures with her children; when possible, they’ve accompanied her on her journeys. “Their experiences are not abstract: they have tasted soil, climbed trees, slept under the stars, and swam in fresh water,” she tells me.

“Water has shaped their childhood in the hopes that it lays the foundation for their adulthood. We conversate passionately about the joy and refuge we find in wild places. They have witnessed the degradation and the beauty. They will hopefully give voice to the challenges of the future through their experiences, just as I am trying to do in the present.” We asked her more about her relationship with water, the joys and terrors of the natural world, and her hopes and fears for the future.

What are some of your earliest memories of water and rivers?

“One of my earliest memories of water is going to my uncle’s house on Lake Burton north of the city of Atlanta, Georgia, where I grew up. I remember my older cousins telling harrowing stories about the town of Burton that was drowned out due to the damming of the lake by Georgia Power. The state of Georgia has no natural lakes. Georgia Power created all the lakes in Georgia for the purpose of power, so many small, poor communities were forced to evacuate.

“It was said that once the dam was closed, the water rose so fast that the infrastructure of whole towns was left behind and for years in Lake Burton you could see the church steeple underneath the water. I heard tales of people refusing to leave their beloved homes regardless of the increasing water levels.

“I was haunted by the ghost stories of the people who remained. I would lay in bed, hearing the water outside and imagining the faces underneath. This was a very heartbreaking and powerful image to me as I rode around the lake in my uncle’s pontoon boat, imagining log cabins and human relics that remained underneath. The idea of the human desire to control rivers regardless of consequences took root inside me through these haunting tales, even though I now realize many were told to simply frighten a young, shy girl.”

Why these seven rivers? How did you choose them?

“I began planning this project in Graduate School. At first, I wanted to follow all the rivers in the United States but as the idea took on more shape, I realized I needed to narrow it down. I decided to focus on rivers that defined regions, major metropolitan areas and rivers that had played an integral role in shaping modern-day America.

“The pandemic has shifted my focus to rivers that I consider my home watersheds, the Snake and Teton Rivers which flow into the Columbia River. I am grateful for the time I’ve spent shooting my own watersheds. I feel it has inspired new ways of looking at what is familiar. I look forward to finishing the seven rivers of my project and seeing how this time at home will translate into shooting the unfamiliar again.”

Were you ever afraid of the natural forces you encountered on these journeys?

“I have had many harrowing encounters in the natural world while shooting Seven Rivers. Here are a few that stand out the most:

“I was caught in a lightning storm on top of the Centennial Mountains in Montana trying to find the upmost source of the Missouri River. I was with a friend who knew the way and luckily had brought a box of matches. We started the trek in the morning and were supposed to return by dinner, but when the storm struck, we had to take refuge under a canopy of trees and start a fire to stay warm.

“This was an extremely strong summer storm that was not forecasted that morning. Lightning was striking all around us. I could feel the electricity in my body, though I was miraculously never struck. We had to hike out that evening when things finally settled down and didn’t return home until midnight.

“My second harrowing encounter happened while camping in the John Muir Wilderness. A close friend, Wenxin, joined me for this backpacking adventure, though she had never done any backcountry camping or hiking. She kindly trusted me to organize the trip. We picked up our permit and bear canisters at the wilderness office in Yosemite Park then set out on our trek.

“On our second night camping, I had just gotten our campfire lit and was starting to cook spaghetti when I heard a low growl. Wenxin was sitting around the campfire taking her contact lenses out so was completely blind for the moment. I turned in the direction of the growl to see a black bear ready to charge us. I had only a moment to react knowing I was the only one that could get us out of this situation.

“My reaction still surprises me to this day, but I decided to charge the bear with only my pot in hand before he could charge us. Fortunately, a woman screaming and running towards him with a pot scared him off. Maybe it was a good thing that my friend was blind during the encounter because she was unafraid to continue with our adventure.

“My third daunting experience occurred during a canoe trip down the Mississippi River from Clarksdale to Rosedale. I was six months pregnant with my first child, Emmalou. After rafting many Western rivers, I thought the Mississippi River would be easy. My husband and I naively drove to Clarksdale, Mississippi in February to begin our journey. We had a difficult time researching our trip, which should have been a clue for what lay ahead.

“The Mississippi River is rarely undertaken in small hand-powered watercrafts. But miraculously we stumbled upon an outfitter in Clarksdale once we arrived, who had lots of experience on the river but had never undertaken the journey in the cold month of February. He helped look over maps with us and set us up with a shuttle driver after failing to dissuade us from our mission.

“We began the trip in a snowstorm and dry suits over down jackets with fat lighter and matches strapped to our legs. The fire kit was a safety precaution in case we flipped our canoe and made it to land in order to start a fire to survive the chilly water temperatures. I do not feel anyone can understand the breadth of the Mississippi River until you have been on the Mississippi River. In most places, the river is over a mile wide.

“We put in on a small back channel, but within minutes, we entered the mighty Mississippi and realized we had probably made a huge mistake. The river is enormous; the riverboat traffic is frightening, and the army corps of engineers has built punishing wing dams to force traffic into the middle of the river making it impossible to hug the bank. We had no way of turning back; we had to continue this five-day canoe trip.

“On the second day, we almost lost our lives. We decided to cross the river, which was always the scariest part of this canoe trip because of the riverboats. You had to be completely sure that there was absolutely no riverboat in sight because to cross the river took about an hour and our canoe might have well been a bird to these captains! A riverboat can’t just slam on the breaks if they realize they are about to hit you. Anyways, we misjudged a riverboat that we thought was parked, and, halfway across the river, we realized our mistake.

“My husband was the captain of our canoe, so he was steering, and I was paddling my heart out listening to his directions. As we realized our mistake, we also realized our life was in danger. And, of course, at that moment, my husband’s paddle shaft broke off and floated downstream. We were in a complete panic. He grabbed our extra paddle, which was held together by duct tape. We made it to shore within minutes of being mowed down by a riverboat. We both cried and promised each other that we would never canoe the Lower Mississippi river again if we survived the rest of the trip.

“Lastly, this project was inspired by a twenty-five-day rafting trip down the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon. I have a deep respect for water after running a river that scared me daily. I was frightened most nights, hearing the rapids that I knew I would be running in the morning. I feel that we should all have deep respect for the natural world, and maybe that is only gained by being a little frightened of it as well.”

What is your most powerful memory from your time working on this series?

“The most powerful memories for me are the ones I have shared with my children. When I was pregnant with my son, my daughter and husband accompanied me to Big Bend National Park to shoot the Rio Grande River. At the time, the news was centered around Trump’s Wall. As I was photographing, my daughter was playing in the river, unconcerned about what side of the river she was playing on. The idea that she was swimming back and forth from Mexico to the United States was of no concern to her. I know this was a privilege because she was three years old and a white American citizen.

“But watching her put things into perspective for me the ridiculousness of arbitrary human lines that we have drawn all over the landscape. How can you build a wall in the middle of the river? The river will exist far beyond the reach of politics. It is unconcerned with this outlandish act, just as my daughter was as she covered herself in Rio Grande mud. She brought me peace and perspective during my shoot. I joined her in being joyful over a beautiful river in a beautiful place and tried to leave my political baggage behind for a few days. I think her playful spirit deeply inspired my work while in Big Bend National Park.”

What signs of degradation, if any, did you observe while visiting these rivers?

“Sadly, I do not even know where to begin with this question. There is so much degradation everywhere, even in the places that seem most pristine. I will say some places still offer hope, while others feel hopeless. I must make sure to spend a bit more time in the places that feel hopeful because if I were to spend too much time in the places that feel hopeless, I am not sure I could continue with this project.”

You began this project in 2013. How has your relationship with it changed in the intervening years?

“I have moved from San Francisco to Georgia to Idaho during this time. I have had two children. I have discovered many grey hairs and experienced three American presidents during this project. Over the last eight years, my relationship with the landscape has changed deeply. In my twenties, the landscape was something I theorized and spoke out about politically. I had a personal relationship, but it probably existed in a youthful abstraction.

“Now that I am married to an organic farmer, raising our children in a drought-stricken western landscape, my relationship with rivers and the breathtaking greater Yellowstone ecosystem that I call home has become fiercer. It’s no longer something that I theorize about in social circles or in my studio practice. My relationship with the landscape is daily.

“I feel it more in my heart more than in my head now that I have children who I want to grow up in wild places without the constant threat of wildfires, now that I have a home on a farm growing healthy food for our community that I worry about not being able to irrigate, and now that I can put in perspective the statistics of greenhouse gases as I can more clearly see our future. I try never to take for granted every time I swim in a clear river or high mountain lake, picnic by a stream, or witness the sight of a glacier. Eight years ago, maybe I was beginning to understand this, but time has made this more poignant.”