Search this site

The World’s Iconic Skyscrapers, Reimagined

“I grew up in a rowhouse-style apartment building in a small town in Israel,” the photographer Niv Rozenberg tells me. “Architecturally speaking, it wasn’t anything special: two long rows of buildings with grassy areas in between, where I spent most of my childhood playing.” His interest in architecture blossomed in college, as he spent time poring over photobooks and learning about the Düsseldorf School of Photography, sometimes known as the “Becher school” after its influential founders, Bernd and Hilla Becher. It was during this time that fell in love with the idea of “perfect symmetry.”

Rozenberg moved to New York for graduate school. “I was overwhelmed with the city’s massive volume and density,” he remembers now. “I started reading Rem Koolhaas’ Delirious New York while taking a few classes in the architectural department at Parsons. At that time, I lived in the Financial District (on Wall St), surrounded by skyscrapers.”

He longed to capture the buildings he encountered every day, but he felt that, in many ways, everything in New York had already been photographed. In 1904, Edward Steichen photographed the Flatiron. In 1929, Walker Evans immortalized the Brooklyn Bridge. In 1932, Berenice Abbott leaned out the window of the Empire State Building.

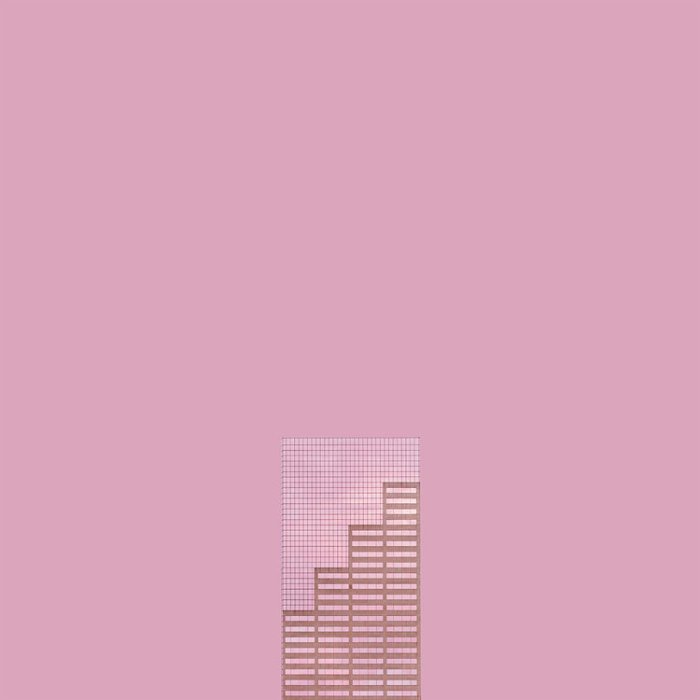

“With the idea that these high-rises are somewhat of an extrusion of the city’s block, I started photographing them by pointing my camera to the first few levels, and then ‘building’ the rest of the facade on the computer,” Rozenberg says. “I was scanning every floor and every window, removing any clutter and basically isolating the buildings from their congested surroundings. In this series, Automonuments, the images capture a somewhat ‘impossible view’ of these buildings, showing them in their most perfect form, at eye level void of any clutter or distractions.”

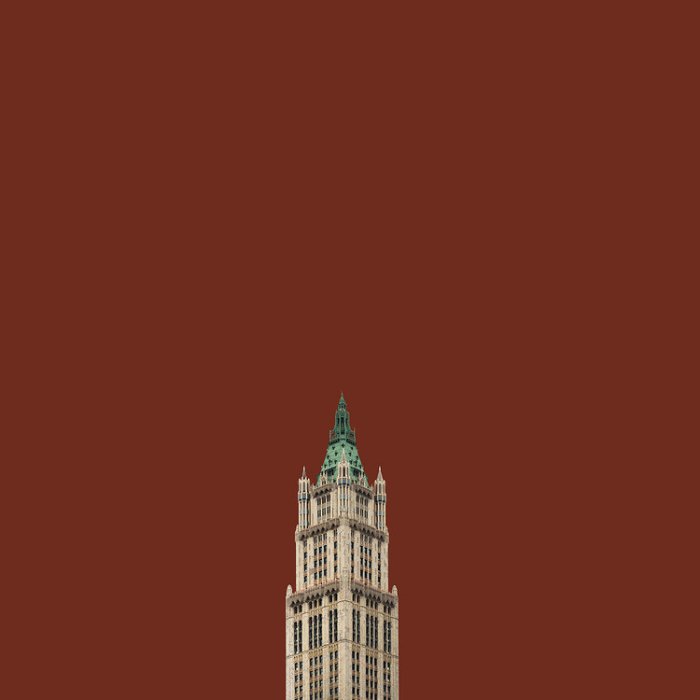

That project would ultimately give birth to another, an ode to skyscrapers. “I was inspired by the views I saw while working on the 36th floor of the Empire State Building,” the artist explains. “The perspective of seeing the tops of skyscrapers was such a different vantage point to observing the city. Instead of looking up, the city’s view was at eye level. With my previous work in mind, I wanted to continue documenting these iconic structures, but now from the unique perspective of a bird’s eye view.”

Titled Summit, this series combines the rigorous photographic aesthetics of the Düsseldorf School with digital manipulation to create perfect (and often symmetrical) structures. “I’ve come to know some pretty interesting facts about NYC,” Rozenberg admits. “For example, The Empire State Building was the first building to have over 100 floors and was the tallest building in the world for about 40 years.

“It was also built in record time–just over a year–and has its own zip code.” From the Chrysler Building and Times Square Tower to the Corinthian, once the city’s largest apartment building, and 56 Leonard, nicknamed the “Jenga building,” each of Rozenberg’s skyscrapers has been stripped of their surroundings, isolated, and set against an expanse of color.

The post-production is meticulous and requires more time than the shooting itself; the final product is always different, emerging like something from an architect’s dream. “Working on its digital construction, assembling the puzzle, is very therapeutic,” the artist says.

While the idea originated in New York, Summit has since taken the artist around the world, with stops in Albuquerque, Portland, and thousands of miles away in Tel Aviv. His colorful backgrounds sometimes take on the hue of the buildings themselves. Sometimes, they represent the building’s complement, as is the case with Tel Aviv’s Azrieli Sarona Tower, aglow in yellow and set against a field of purple.

Between his travels, Rozenberg still makes time to visit the town where he grew up. “It’s funny because I recently visited a ‘high-rise’ from my childhood,” he tells me. “It was the tallest building in town, and I used to walk by it every day after school. It’s actually only twelve floors and not that tall, but that was our neighborhood’s ‘skyscraper.’”

All images © Niv Rozenberg