Search this site

In 1902, a Black Performer Took the World by Storm. Her Story Resonates Today.

“Aida Overton Walker was someone I needed deeply,” the British Ghanaian visual artist and actor Heather Agyepong tells me. A turn-of-the-century vaudeville performer, Overton Walker earned worldwide stardom and the title the Queen of the Cake Walk, named after a dance that became a cultural phenomenon. During a period when Black performers were given few opportunities on stage, her life’s work stands as a masterclass in creativity and resistance.

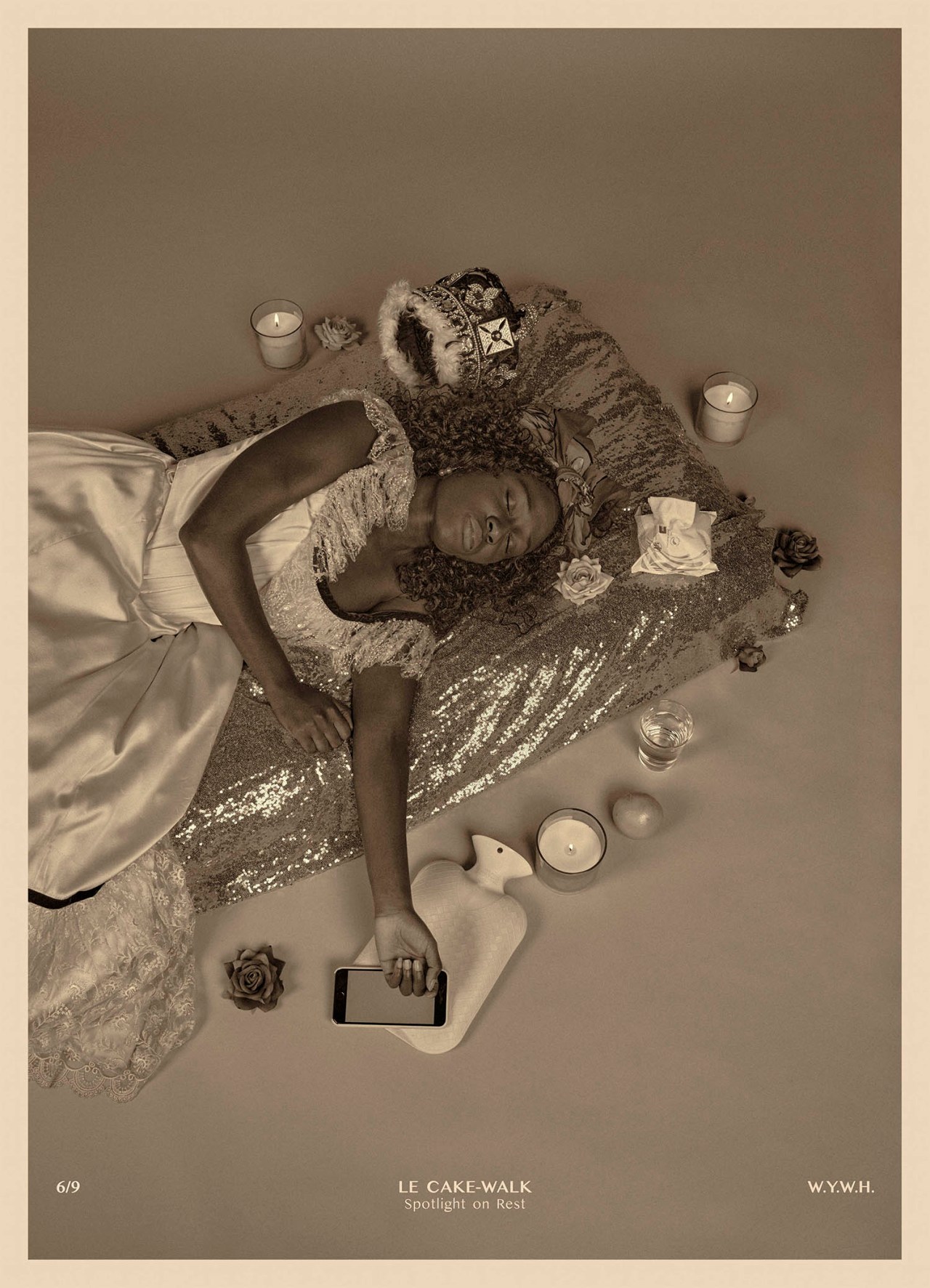

When Agyepong, who works with photography as well as performance, discovered Overton Walker’s work more than a century later, she was enchanted. Although Overton Walker passed away in 1914, Agyepong would step into her shoes, bringing her back to life and embarking on a new kind of collaboration, spanning generations. In Wish You Were Here, commissioned by The Hyman Collection in 2019, Agyepong plays the role of the legendary vaudeville performer.

The dance itself—the Cake Walk—has a complicated history—and it’s one rooted in subversion. Before slavery was abolished (less than half a century before Overton Walker’s rise to stardom), enslaved people created The Cake Walk to imitate their enslavers and satirize “high society.” As Agyepong explains, these enslavers might (or might not) have understood the meaning of the dance, but it caught on, and many hosted competitions for enslaved people.

After slavery was abolished, the dance continued to trend, earning its name from the cake that was awarded to the best performers. By the turn of the 20th century, however, minstrel shows had incorporated racist depictions of the Cake Walk. At the same time, racist postcards, featuring cartoonish and dehumanizing pictures of Cake Walk performers, became popular in Europe. Agyepong saw some of them while making this work; they were shocking and grotesque.

But this was also during this time that Aida Overton Walker built her career. As a performer, she took the Cake Walk and turned those portrayals upside down, revealing the grace and agility required for the dance, defined by high kicks and struts. By 1903, she’d soared to fame following the landmark musical In Dahomey, one of the first hit Broadway musicals to be written and performed almost entirely by Black artists.

“When I heard about this so-called ‘Queen of Cake Walk’ and how she flipped those postcard depictions, I thought, ‘There is really something here,” Agyepong reflects. “How can we Houdini power?” In Wish You Were Here, she plays the role of the magician: using the aesthetic of the old postcards, she portrays a woman with power and agency.

“In the early 1900s, Overton Walker said, ‘Unless we learn the lesson of self-appreciation and practice it, we shall spend our lives imitating other people and deprecating ourselves,’” the photographer explains. It’s stuck with her.

Agyepong spent about a year researching the performer, immersing herself in her life and work. “I was also digging into my life, thinking what liberated space meant to me, what ownership and rest looked like,” the artist says. In The Body Remembers, she uses white paint and lavender flowers to visualize trauma and ways of coping with it. In Rob This England, she’s wearing a crown—a reference to the time Overton Walker went to Buckingham Palace to perform for the birthday of the Prince of Wales.

There are references to today’s popular culture hidden in there too. In one of the photographs, Anne Mae, the photographer is (in part) referencing a now-iconic gif featuring Viola Davis on the television show How to Get Away With Murder. In that scene, Davis’s character, Annalise Keating, is standing up, picking up her purse, and leaving a meeting.

In that way, the lines between past and present—and between the photographer and her muse—start to blur. The two of them are talking, unbound by the rules of space and time. “She’s telling me, ‘I wish you were here—-where I am and how I feel, grounded and commanding,’” the photographer says. “I’m telling her, ‘Well, I wish you were here, where you could have taken up the space that was rightfully yours.

“It’s an homage to our past and present circumstances as black female artists. At the time, Overton Walker felt like an aspiration. I think part of her fight always lived in me, but something about having that conversation within the images allowed me to really own it. Communion, sisterhood, and conversation are where real healing can happen for me.”

The work is timeless by definition. But at the same time, it feels meaningful that Agyepong made the photographs at this precise moment in global history, one marked by injustice but also change and hope. In 2020, the pandemic disproportionately affected Black families and Black women. It was also the year the Black Lives Matter movement inspired millions and reshaped the world forever. These photographs are just as important today as Overton Walker’s work was in 1903.

In Wish You Were Here, Agyepong is playing a part, based on a real person. But she’s also simply being herself. In some ways, that’s the most stunning magic trick of them all: in becoming someone else, she’s actually coming into her own. “Making this work was a joy, but it was also heavy—because there were/are parts of myself which I’ve felt are too loud or too much,” she tells me. “This series was about processing that. I think all my work is about processing and reflecting on where I am now and where I’m going—to pay respect to me in the grey and the gold.”

Wish You Were Here will be on view at the Centre for British Photography from January 26th to April 30th.

Heather Agyepong is a member of Black Women Photographers, a global community bringing together Black women and non-binary photographers. To learn more about Black Women Photographers, visit their website, and follow along on Instagram at @blackwomenphotographers.

All images © Heather Agyepong