Search this site

‘The New Big 5’: Wildlife Photography of Endangered Species from Around the World

Mountain gorilla

Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda

IUCN status: Endangered

“This is Marambo, one of the largest silverbacks in Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park, taken on the forested slopes of Sabyinyo volcano. The head of the Mahoza family, he’s a gentle giant, weighing around 200 kilograms. He spends most of his time as a quiet, powerful presence watching over adult females, juveniles and babies in his group.

“Mountain gorillas are challenging to photograph, as they move quickly in and out of undergrowth, the light and positioning constantly changing, and you can’t get too close, for their sake and yours. I wanted to take up-close portraits that give a sense of what it’s like to stand eye-to-eye with the world’s largest primate and one of nature’s wonders.

“Gorillas share more than 98 per cent of their DNA with humans. They’re also vital to forest habitats, controlling plant growth and distributing seeds. Mountain gorillas are found in just three countries: Rwanda, Uganda and Democratic Republic of Congo. Their two ranges total less than 300 square miles.

“Mountain gorilla populations are slowly recovering. They’ve been moved from Critically Endangered to Endangered by the IUCN. It’s a sign that global attention and conservation efforts from wildlife organisations, governments and local people does work. We just need to make sure there’s more of it.”

Last year, the photographer and journalist Graeme Green traveled to Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda to see the mountain gorillas. “Being up close to the world’s largest primate is an experience you never forget,” he tells me. “I spent time with a 200-kilo silverback called Marambo.” Gorillas and humans share 98% of our DNA, and it’s evident in Green’s portraits of Marambo, which are The New Big 5, a book of wildlife photography from more than 145 contributors.

The book—and Green’s larger project of the same name—is a reclamation and reimagining of the “Big 5,” a term used by trophy hunters to describe the animals they hoped to kill and mount on their walls. Green’s idea was both ambitious and straightforward: instead of shooting these magnificent animals with guns, what if we redirected our attention to protecting them and raising awareness through photography (a different kind of “shooting”)?

The photographer organized a public vote to determine the “New Big 5,” or the animals people most wanted to photograph and see in photographs. In the end, the people chose elephants, tigers, lions, polar bears, and gorillas like Marambo.

In the 1970s, mountain gorillas were on the brink of extinction. Swaths of their habitat were destroyed, and they were hunted as trophies. But the mountain gorilla survived. “Mountain gorillas are a conservation success story that gives hope for the future,” Green says.

“Thanks to conservation work from organisations, such as Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund and Conservation Through Public Health, and the work of governments and local communities, their numbers have steadily risen.” According to the most recent census in 2018, their numbers are at 1,063. As those numbers increase, plans have been made to expand Volcanoes National Park.

Across the globe, animals are in crisis, but the story of the mountain gorilla and others like it prove that we can still reverse course, ensuring a future for wildlife and humans alike. The New Big 5 book, published by Earth Aware Editions and distributed by Simon & Schuster, is about all wildlife, large and small. The five species selected by public vote represent a point of departure, leading the way for dozens of other species, who are revealed along the way.

With essays from pioneering conservationists and activists and images from passionate photographers, The New Big 5 provides a potential roadmap for humankind—and it’s one we must follow for there to be any kind of future for our planet and its many inhabitants. We asked Green to tell us more.

The New Big 5: A Global Photography Project For Endangered Wildlife by Graeme Green is out now (Earth Aware Editions; $75.00; £60.55), available at Insight Editions.com, Amazon, and Bookshop, with a foreword by Paula Kahumbu and an afterword by Jane Goodall.

Can you tell us a bit about the process of creating the New Big 5 book?

“The book took around two years to put together. I wanted there to be real substance in terms of information and ideas to go alongside the beautiful wildlife photography, so for the chapters I wrote, I did a lot of research and interviewed experts around the world, from Kristine Tompkins (Tompkins Conservation) to Daniel Sopia (Maasai Mara Wildlife Conservancies Association), to include their comments and ideas.

“I also spent a great deal of time editing and working on the essays from the contributors, including Jane Goodall, Tara Stoinski (CEO, Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund), Dominique Gonçalves (Manager, Elephant Ecology Project at Gorongosa National Park), and Wes Sechrest (CEO, Re:wild).

“But the most time-consuming aspect was curating the photography. More than 16,000 photos were submitted by photographers all over the world, which meant working weekends and late nights, juggling the demands of producing the book with working as a journalist and photographer to make a living. I also scoured through Instagram accounts and websites for a particular type of photo or a specific endangered species. I wanted every single photo in the book to merit its inclusion—every photo had to be outstanding.

“I also wanted to make sure the book represented photographers from all over the world. The book includes many great female photographers and Black, African, Asian, and Latin American photographers. There’s outstanding talent all over the world. Wildlife photography has a real issue with ‘diversity’—it’s often a space dominated by white, Western males. I didn’t want to put out a book that just perpetuated that idea. I wanted to try to be part of the solution and for the book to make a difference on this issue.

“There are photographers in the book from India, Botswana, China, Kenya, Ecuador, Kuwait, Mexico, Brazil, Japan, as well as from the UK, US, Australia… The book and the images are all the stronger for drawing on the real talent that’s out there, rather than just a small sub-section, which has always seemed a strange and limited way of thinking to me.”

Bengal tiger

Bandhavgarh National Park, India

IUCN status: Endangered.

“The tiger is one of my most favourite animals to photograph. I travel all the way from Canada to Indian forests to capture their majestic beauty. Ranthambhore is another national park in India which I often visit, which is filled with majestic tigers. But this picture was taken in Bandhavgarh. Local people and officials in India are trying to protect the tigers in whatever way they can and the tiger population is now increasing in a large scale. This picture was taken on a rainy day. In Indian forests, it’s very difficult to get a proper picture of a running tiger, as they all are thick forests. I kept the camera settings fast enough to freeze the running tiger.”

African elephant

Lower Zambezi National Park, Zambia

IUCN status, Endangered.

“I shot this image in Lower Zambezi National Park, Zambia. It’s the direct result of my favourite creative tool: previsualization. My approach is often the opposite of what most wildlife photographers do – instead of going where the animals are, I go to where I want the animals to be. The landscape and the setting is more important to me than the species. In this case, I spotted this beautiful constellation of tree trunks and immediately saw the potential for a great animalscape. I decided to get into the perfect position and simply wait for an animal to walk into the natural frame.

“Luckily, the area has plenty of elephants, so eventually an elephant walked into my frame and I couldn’t have been happier. The elephants in this area have relatively small tusks, and many of them have no tusks at all. This is the result of what is called ‘reverse evolution’ – the survival of the weakest. Poachers are always targeting the biggest bulls with the largest tusks, so their genes are eliminated from the gene pool. The weakest bulls – the smaller ones with small tusks or even no tusks at all – survive and get to procreate. I have been going to this area for over 15 years now, and every year I see more tuskless elephants. I was lucky that this particular bull had sizeable tusks.”

Tswalu Kalahari Reserve, South Africa

IUCN status: Vulnerable

“At over 120,000 hectares, Tswalu Kalahari Reserve is South Africa’s largest private protected area. Laying on my stomach on the floor of a photographic vehicle, this rough-and-tumble image captured one moment in a wonderful fifteen minute session of sneak attacks, tugs-of-war and wrestling at a waterhole, while the youngsters’ mother rested with the other adults in the shade of a nearby tree.

“Though it is easy to take the presence of lions for granted, as they are certainly abundant in online safari posts, it is easy to forget that the population size of Africa’s largest predator has shrunk to a fraction of what it was a few decades ago. This is largely the result of their habitat having been destroyed, which increases conflict with an ever-growing human population, usually to the lions’ detriment. Though the threats to their future have by no means disappeared, lions have been successfully re-introduced to parts of Africa where they had previously been driven extinct.”

Ethics are vital in wildlife photography. Can you tell us a bit more about the requirements you set for the photographs and photographers featured in the book?

“It was important to me that we avoid any photos that might have caused any harm to wildlife. So we asked every photographer to sign a contract to say they hadn’t used baiting or any behaviour that could cause stress or harm to the animals for their images, and that all photos were taken in the wild, rather than at zoos or ‘sanctuaries,’ where animals are often kept in poor conditions or forced to perform for photos.

“I also wanted the photos to represent reality. We applied standard photography competition rules really, which was to say that we didn’t want fake images that had been produced with creative editing in Photoshop.

“As well as one chapter each for the New Big 5 species (elephant, tiger, gorilla, polar bear, and lion), I put together an extensive chapter on endangered species. For that, I only included species listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable, or similar in-country assessments.”

Polar bear

Wapusk National Park, Manitoba, Canada

IUCN status: Vulnerable

“I saw this polar bear family pause on its trek to the sea ice to hunt seals on a frozen day in the Arctic. At this moment, these adorable twin cubs turned their first adventure into playtime by using their patient mum as a playground. They were only around three months old and had just emerged from their maternity den several days earlier.

“Since the polar bear cubs are young and helpless in the harsh Arctic, they rely on their mother for everything they need to survive. They are inseparable all the time until the cubs are about two and a half years old. The weather was – 40 degrees C, accompanied by intense Arctic wind. But it was a privilege to get this image in a restricted Arctic denning area at Wapusk National Park, Canada, which I’d gained permission to enter.”

Cape Pangolin

Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique

IUCN status: Vulnerable

“We found this wild ground pangolin, also known as the Cape pangolin, during a biodiversity survey in Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique. She was out foraging for termites and I took a series of photos of her. Pangolins are the only mammals that have large scales made of keratin, which are actually just modified hairs.

“These animals are coveted in Asia for their meat and scales, which are wrongly thought to have medicinal properties. As a result, they are one of the most trafficked animals in the world. In recent years, all eight pangolin species were protected under the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).”

Throughout the process, did you learn anything from conservationists that surprised you or moved you?

“I learnt a lot. I worked on the book for two years and talked to many conservationists, scientists, and other experts for interviews that I included in the book, from Frans Schepers (Executive Director of Rewilding Europe) to Indigenous Amazon campaigner Nemonte Nenquimo (Amazon Frontlines).

“I think the present situation facing wildlife, nature, and the environment is dire. So one of the things I wanted to do with the book is explore solutions and look at hopeful signs. And there are signs of hope to be found, including animals, such as mountain gorillas, West African giraffes, Nassau grouper, and Lord Howe Island stick insects, that have been brought back from the brink of extinction.

“New protected areas have been created. Community projects are helping people and animals coexist. Rewilding efforts are restoring species and ecosystems that were at risk of being lost. Conservation does work—we just need a lot more of it and more urgency to it.”

Green Sea Turtle

Ningaloo Marine Park, Australia

IUCN status: Endangered

“This is a solo green sea turtle on the Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia. While out snorkelling on the back of the reef, my friend called out that she had found a large school of glass fish under a ledge at about ten metres down. When I dived down, the wall of glass fish opened up to reveal a perfectly framed turtle, which seemed to be having a rest before turning and looking directly at me. I had time to take four photos before I needed to come up for air. When looking back at them, I knew it was one of the best moments I had ever captured.

“From hatching, this turtle faced less than a 0.001% chance of surviving to adulthood. Sadly, sea turtles face significant threats from climate change, habitat loss, coastal development, pollution, feral animal predation, vessel strikes, commercial and recreational fishing by-catch and marine debris entanglement and digestion. With increasing challenges to their survival, I hope that we can work together to protect such a magnificent creature for future generations to admire.”

Ruppell’s Vulture

Simien Mountains National Park, Ethiopia

IUCN status: Critically Endangered.

“This image is of a Ruppell’s vulture in flight in front of the Jinbar Waterfall in the Simien Mountains, Ethiopia. The Ruppell’s vulture is a large bird of prey, listed as Critically Endangered according to IUCN. The current population of 22,000 is decreasing mainly due to loss of habitat. Ruppell’s vultures are also considered to be the highest-flying bird, with confirmed evidence of a flight at an altitude of 11,300 m (37,000 ft) above sea level.

“Vultures usually climb the steep walls of the gorge into which the waterfall flows to take advantage of the updrafts that form during the day. In this image, the light that filters from above into the gorge illuminates the birds in flight, leaving the background in darkness, creating a strong sense of contrast between light and shadow. “Vultures are essential to the health of an ecosystem. As scavengers, they serve a clean-up role. But their numbers have decreased dramatically across Asia and many parts of Africa.”

Do you have a personal favorite story of humans (or a human) helping wildlife that you learned about over the course of making the book?

There are many. One person I’d talked to before for a podcast on the New Big 5 website and included in the book was Farwiza Farhan, environmental activist and founder of Forest, Nature, and Environment Aceh (HAkA). This is a really inspiring story.

“Farwiza Farhan fought the palm oil company Kallista Alam in Indonesia’s Supreme Court in 2015 and won. Kallista Alam was forced to pay $26 million for illegally setting fires and clearing land for palm oil plantations in the Leuser Ecosystem—6.4 million acres of biodiverse rainforest habitat, the only place in the world where the Sumatran orangutan, rhino, tiger, and elephant still live in the wild.

“‘Anger can drive people to take action,’ Farwiza told me. Leuser remains at risk from deforestation and commercial exploitation. But the fines handed down to the company showed the Indonesian government would punish illegal environmental destruction. And Farwiza believes this only happened because so much international attention was focused on the case, which shows how important it is that people get involved.

“‘We can’t look toward the future and have the spirit to move forward if we always assume the worst will happen,” Farwiza said. ‘Seeing the realities on the ground can be disheartening, but we have so much we can win back. None of us can do it alone. Our legal victory can bring hope and strength that, if we work together, this battle is winnable.’

“I also drew on my own experience as a journalist. Years ago, I visited remote Ashahinka tribes in the Peruvian Amazon and also campaigners in Chile both fighting to stop hydroelectric dams being built in their regions, which would have destroyed the local environment, wildlife, and many people’s livelihoods. I wasn’t overly optimistic that they would be successful, going up against powerful industries and governments. But in both cases, they won. With an avalanche of bad news stories, we need to remember that people often do make a stand and win an important battle.

“As Jane Goodall says in her closing essay in the book: ‘We can all make a difference, but it’s up to us the kind of difference we choose to make.’”

Cuban Crocodile

Ciénaga de Zapata National Park, Cuba

IUCN status: Critically Endangered

“It is estimated there are only 2400 mature individual Cuban crocodiles (Crocodylus rhombifer) left on Earth. This tiny population found only in Cuba faces many threats, but the largest one stems from interbreeding with American crocodiles whose numbers and range is far larger than that of the Cuban croc. As the sea rises due to climate change the range of American crocs (who prefer sea water) expands, and overlaps with the shrinking Cuban croc’s territory (which is typically more brackish, swampy water).

“I had already photographed the American crocodile in Cuban waters and that’s how I first heard about the plight of the Cuban croc. I went back the next year specifically to photograph an individual Cuban crocodile who was hanging out in a cenote in Zapata National Park. This male was still relatively small and had seen a lot of people in his life because a popular walking trail ran next to the cenote. Had the croc been larger or if he had had other croc friends nearby it would not have been safe to get in the water. While Cuban crocodiles are considered to be one of the most aggressive crocs, I found this one to be very polite.”

Polar bear Baffin Island, Nunavut, Canada

IUCN status: Vulnerable.

“I photographed this polar bear wandering along the floe edge where sea ice meets open water in the high Canadian Arctic. We had tracked this bear for several days, and after two weeks it was my last day out on the ice. We watched his brazen personality and curiosity as he wandered close to snowmobiles and camps. I popped my drone off to get a landscape photo of him. I think this image shows that you don’t need to get really close to animals to get an impactful image. “

Something we should always be conscious of when out there documenting wildlife is the impact we have in the moment on their wellbeing. Bears are living their best life here on the sea ice. The number one threat for polar bears is the deteriorating sea ice condition year after year due to climate warming in the Arctic. It is not just a platform to hunt and commute, but it’s also vital for their main prey seals to den and nurse their pups. It is also the substrate that sea ice algae grow on, which is very much at the base of the Arctic food chain. A bear walking away seems to imply the state of a runaway climate crisis if we do nothing to turn things around.”

African Elephant

Ruaha National Park, Tanzania

IUCN status: Endangered

What are some of your most powerful memories from your time working in wildlife photography, and are these moments included in the book?

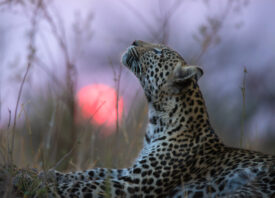

“The photos of mine in the book range from the last ten years or so, from penguins in Antarctica to leopards in Tanzania. These are many of my favourite wildlife photos that I’ve taken and favourite memories. Photographing mountain gorillas in Rwanda has been one of them.

“Additionally, some of my favourite photographic memories are of spending time with smaller creatures. There are photos of mine in the book of a blue-eyed anglehead lizard, a golden tree frog, and a dung beetle. It’s important we don’t just focus our attention on iconic species.

“This is really the message of the New Big 5 project and the book: that all wildlife, from bees to blue whales, are essential to the balance of nature, healthy ecosystems, and the future of life on Earth. Looking at the photos in the book is a very powerful experience, with so many images of remarkable animals, from rhinos to vultures, that could be lost forever, if we don’t change path.”

Cheetahs

Mara Naboisho Conservancy, Kenya

IUCN status: Vulnerable

Graeme Green

African lions

Naboisho Conservancy, Kenya

IUCN status: Vulnerable

“Lions are one of my favourite animals to spend time with. Hearing them roar their territorial warnings across the grasslands of Kenya is unforgettable.

“Lions are powerful animals, global symbols for strength, courage, and nobility, With this photo, I wanted to show their gentle, affectionate side and capture the behaviour between these two brothers who roam Naboisho Conservancy together.

“Perhaps because lions are such powerful, fearsome animals, many people think they’re doing fine. But like many other species currently, their numbers are declining rapidly. African lion numbers have declined by around 50 per cent in the last 25 years. They currently occupy just eight per cent of their historic range. Bushmeat hunting (which reduces lions’ prey), habitat loss and human-wildlife conflict are all major factors.

“Lions are an apex predator. Remove them and the balance between predator and prey is lost, which can have an impact on an entire ecosystem.

“The idea behind the New Big 5 project and book is to highlight the importance of all species, from bees to blue whales, to the balance of nature, healthy ecosystems, and the future of life on Earth.”

Further Reading:

• Paul Nicklen Captures the Beauty and Fragility of the Polar Regions

• Rescuing the Pangolin, the World’s Most Trafficked Animal

• 8 Common Ethical Mistakes in Wildlife Photography (And How to Fix Them)