Search this site

From the 1970s to Now, Mariette Pathy Allen Traces Transgender Stories

“I got very little respect for this work for a long time,” Mariette Pathy Allen tells me, remembering her early days photographing and collaborating with gender-nonconforming people throughout the United States. “Publishers thought the subject was too limited. Galleries didn’t find the pictures very exciting because my images de-sensationalized the subject matter.”

Back then, she took matters into her own hands, traveling far and wide to share the stories of the people she’d met through slideshow presentations. Now, decades later, her life’s work is being recognized as part of the retrospective exhibition Breaking Boundaries: 50 Years of Images at Culture Lab LIC, curated by Orestes Gonzalez and Jesse Egner.

To coincide with Pride Month, the exhibition will open alongside a second exhibition, Breaking More Boundaries, curated by Allen, Gonzalez, and Egner. Breaking More Boundaries will feature the work of artists who’ve been inspired by that legacy, including invited artists Zackary Drucker and Jess T. Dugan as well as those who submitted via an open call.

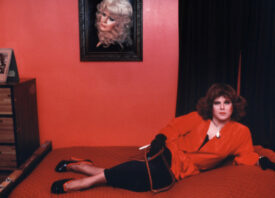

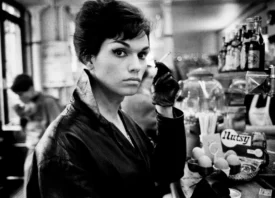

Allen’s decades-long work was inspired, in part, by a serendipitous encounter on Mardi Gras in 1978. While staying in New Orleans, she met Vicky West, a transwoman who would later introduce her to the transgender conference Fantasia Fair. She’s spent the years since then traveling, photographing, and collaborating with gender-nonconforming people and the families and communities they’ve built.

She still remembers ringing the doorbell of Amy and Rita’s house in the Boston suburbs in 1983. “When the door opened, I was greeted by a beautiful black and white great dane,” she says. “In the living room, I saw Amy wearing a white dress, and her husband, Rita, a black one. Then the three of them sat down on the sofa, six legs in a row.”

That portrait is one of the photos Allen used to include in her slideshows—and it’ll be on view as part of the retrospective exhibition as well. We asked her to tell us more about how the upcoming exhibitions came to life.

You’ve collaborated with the trans community for 50 years now. Why do you think you’ve devoted so much of yourself to telling these stories?

“A lot of the ideas and issues espoused by male-to-female crossdressers–who were the first group of gender-variant people I met, asked questions that I have always asked myself: Why are men and women supposed to have different characteristics and behave in what is considered gender-specific ways? Why do these ‘rules’ exist? What is the essence of a human being?

“Spending intimate time with ‘straight men,’ I got to peek into the lives of firefighters, engineers, computer geniuses, truck drivers, pilots, and the range of what used to be considered masculine professions. As a photographer, I felt as if I were also a therapist in the way I helped the person I was working with to reach the woman who lived inside of them. I helped to free them from the straightjacket of forced masculinity.”

Why do you think the people in your photographs have trusted you over all these years? What do you think it meant to them to see these images of themselves?

“Right from the beginning, the people I photographed trusted me because they understood that I was on their side, that I found them relatable, and shared their goal of helping cis people understand them better. When Transformations: Crossdressers and Those Who Love Them was published in 1989, many people felt joy and relief to finally have a book that they could use to show who they were to their families, friends, and the outside world. I was told that the book saved marriages, and even lives. One transgender woman, who used a wheelchair, told me she read the book every week to help her feel better.”

Please tell us a bit about your time with Fantasia Fair. What are some of your favorite memories from the years you served as the official photographer?

“Although Fantasia Fair is where I cut my teeth, before long I attended other conferences and club meetings all over the US and eventually other countries. Fantasia Fair (now called ‘Transgender Week’) is particularly wonderful; it lasts a week and takes place in Provincetown, MA, where gender and sexual variation is accepted and even enjoyed. The townspeople even refer to the middle of October as ‘the tall ships’ have arrived, referring to the height of the visitors and their shoes.

“The Fair offers all kinds of workshops, and participants are encouraged to be in the fashion show, and the FanFair Follies, to perform almost anything they choose. The town has a range of guest houses, several gay discos, many restaurants, the dunes, and the ocean. I made portraits all over town, at the beach and next to monuments and on the gorgeous dunes. I loved the humorous and unexpected encounters, the feeling of being on a magic island, the playfulness, and sexiness, and vulnerability.”

Will some of the people you’ve photographed over the years be at the exhibition? Are you still in touch with many of them?

“I hope a few gender-expansive people will be there. Oddly enough, most of my good friends from the community live on the West Coast. Most of my friends have aged out and don’t go to the few conferences that are left. Sadly, many of the people I’ve known have disappeared in one way or another.

“Elaine, one of my friends, and I traveled to Fantasia Fair together for many years. At the FanFair Follies, she would create a hula dance outfit, and dance to the music. One year she cut a coconut in half and used one half to cover each breast. I didn’t know how important hula was to her until she told me she joined a women’s hula dance class where she was the only crossdresser. Then to my chagrin, she said she would stop going to Fantasia Fair because the hula company she belonged to was performing at the same time!”

In the last fifty years, what tides and shifts have you noticed, either within the trans community or outside of it (in terms of human rights, awareness, and so on)? What has changed?

“In 1978 and all through the ’80s and even later, when I first encountered gender-variant people, they lived in secrecy, fear, and shame. They felt guilty and ‘knew’ they would lose their loved ones and their jobs if their secret was revealed. Some courageous people did go on television shows and allowed themselves to be interviewed, usually with painful results. There were endless discussions on how to define themselves, and many of the definitions were rigid: crossdressers, transexuals, and drag queens were considered to be separate entities.

“In the ’90s, the transgender community started to become more politically active. As transgender people started to believe in their value as human beings in society, they were less willing to remain at the mercy of medical, legal, and political authorities. Along with the desire to take charge of their lives, they became more open to collaborating with other people from different positions under the LGBT umbrella.

“In the ’90s, there was a coming together of people who live full-time in the gender in which they identify: male-to-female or female-to-male individuals, transgender or genderqueer youth, intersex people, people undergoing facial and/or anatomical surgery, political and social activists, and people in family and relationship variations and innovations.

“The computer made a huge change for everyone. Suddenly you could find many people with whom you could identify and meet, and you could participate in or follow scientific discoveries to understand more about yourself. Academic courses on sex and gender studies became part of the curriculum at liberal arts colleges and universities, and non-binary approaches to life and speech are becoming common. Laws to protect gender-variant people were passed, and Obama was the first President to use the word ‘transgender’ on television!”

Why are these exhibitions so important right now? What’s at stake in our country and world?

“Currently, we’re experiencing a backlash against all the progress that has been made through attacks against the right of the individual to be independent of religious and societal limitations, which has taken so many years of emotional, medical, literary, and legal hard work. The remarkable evolution of the movement for gender rights is being attacked all over the US. I think that the anti-abortion and anti-trans movements are similar as they both deal with the treatment of the body. These attacks are mean-spirited, violent, immoral, and very dangerous. I would add, I think conservative and retrograde values are showing up all over the world. Repression of all kinds seems to be rampant.”

Has your relationship with your own images evolved at all over time? If so, how so?

“As the needs of the community changed, my photographs shifted to becoming more spontaneous. Political events and other activities required faster shooting. I made fewer portraits and used backdrops less. When I used film, I had black and white in one camera and color in the other. After I switched to digital, I only used one camera and stopped thinking in terms of black and white.”

Can you tell us more about these two exhibitions? How were the other exhibiting artists selected, and what does it mean to have your work shown side-by-side?

“I am quoting Orestes Gonzalez, who conceived of the exhibition:

‘Since the late 80’s, I’ve always been a fan of Mariette’s work. Her groundbreaking images of a world I barely knew was both an eye opener and a consciousness creator for a segment of the LGBTQ community still struggling with acceptance and inclusivity.

‘When we did our annual Pride Month group exhibit at CultureLab last year (which featured a triptych of hers), we asked if she would be willing to show her work retrospectively. Her acceptance immediately brought to mind another opportunity: to feature artists whose work was either inspired by her imagery or was brought to light by her opening up avenues that otherwise were closed before.’