Search this site

Henry Leutwyler Traces the Life & Legacy of Philippe Halsman

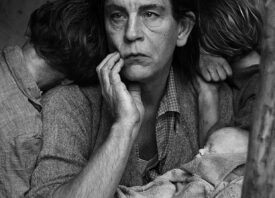

“Objects have a soul,” Henry Leutwyler tells me. Over the span of years, he worked with the Halsman Archive to photograph the objects that belonged to the legendary photographer Philippe Halsman and Yvonne Halsman, his wife, assistant, and master retoucher. That collaboration has culminated in Philippe Halsman. A Photographer’s Life (Steidl), a book that traces the story of one artist’s life through the things he collected, built, and left behind.

Oliver Halsman Rosenberg, Philippe and Yvonne’s grandson, saved many of these items in 2006 when the family left their studio in New York. He kept handmade darkroom tools for dodging and burning, made with cardboard, tape, and wire; letters to and from his grandfather and grandmother; lighting gear; and thousands of other objects. He cut a triangle of linoleum from the studio floor and salvaged rolls of seamless paper dating back to the 1950s.

“Every object is dear to the family… and everything needs to be treated with respect,” Leutwyler says. Oliver Halsman Rosenberg and Irene Halsman, Philippe’s daughter and Oliver’s mother, contributed their memories and research to the book, breathing life into the inanimate objects that passed through Philippe and Yvonne’s hands. In total, Philippe captured a record-breaking 101 covers for LIFE during the magazine’s heyday.

The book includes, for instance, the black stool featured in Halsman’s famous photograph Dali Atomicus, and a red skirt worn by Marilyn Monroe during a studio session (it was actually Irene’s skirt). As Oliver Halsman Rosenberg explains, photoshoots looked different then than they do now: celebrities would show up without managers or stylists, and Yvonne would assist and help with styling. Irene remembers hiding on the balcony with her sister Jane to listen when celebrities came to visit.

In many ways, the book represents a collaboration between two photographers—Philippe Halsman and Henry Leutwyler—running from the past into the present. The two never met; Leutwyler saw the Halsman retrospective at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in 1979. “I remember the exhibit, to this day,” he reflects.

“The ‘old’ ICP on Fifth Avenue and 94th Street was marvelous. The body of work caught my interest more than specific photographs. A body of work is so difficult to achieve; one memorable photograph to be remembered is so easy…”

As a body of work, the book itself spans “thousands and thousands of objects.” Leutwyler admits, “Considering the book has 400 pages, the edit was the most difficult one.” Page by page, the book follows Halsman from his birth in Riga to Irene’s birth and the family’s studio in Paris, to the invasion of the Nazis and the family’s escape to the United States, and through the decades they spent in New York City.

Halsman belonged to a time when you made photographs by hand, and for that reason, the objects of his professional life seem especially personal. Irene Halsman recalls an apartment filled with photographic equipment—and the many wet prints set out to dry on boxes in their apartment; they weren’t allowed to have a dog or cat for that reason (though they did have two turtles). She remembers hearing Philippe and Yvonne through the wall of her bedroom as they worked in the darkroom at night, racing to meet deadlines.

Along with the objects directly related to photography, you’ll also find treasures from Halsman’s travels, including the soaps he collected from airplanes and hotels. “When I was a kid, I did the same,” Leutwyler tells me. “Unfortunately, mine vanished.”

The letters have a chapter unto themselves, with correspondences from John F. Kennedy, Janet Leigh, John Steinbeck, and many photographers—Gordon Parks, Ansel Adams, Yousef Karsh, Richard Avedon, and Irving Penn among them. Leutwyler was particularly struck by a letter from Henri Cartier-Bresson to Yvonne Halsman after Philippe’s death.

Exploring the book is almost a physical, multi-sensory experience, similar to running a hand over the Fairchild Halsman, a specially-designed 4×5 twin-lens camera, or inhaling the scent of soap. Those sensations are the result of Leutwyler’s signature gaze—a way of looking that manages to be both unsentimental and deeply evocative.

Leutwyler prefers not to say too much about his own experiences behind the scenes, giving our imagination room to roam. “I leave [most of the] answers to the readers of the book,” he explains. “Personally, I learned that Mr. Halsman was a very, very funny man; a true photographical genius; and an incredible craftsman, pre-Photoshop. What he achieved in his lab, in camera and conceptually, is absolutely brilliant.”

As it happens, many of the items featured in the book have found a second life. Oliver Halsman Rosenberg uses some of his grandparents’ tools in his own darkroom, and he wears his grandfather’s ties from the 1940s on special occasions. Oliver and Irene gave Leutwyler a 4×5” polaroid of Louis Armstrong (a personal hero to the photographer) as a “thank you” for capturing the objects that meant so much to their grandfather and father, respectively.

“Labors of love always pay off, in one way or another,” Leutwyler tells me. “I am a lucky man.”

Get your copy of Philippe Halsman. A Photographer’s Life here.

All images are from Philippe Halsman. A Photographer’s Life by Henry Leutwyler, published by Steidl.

Further reading:

• Celebrities Get Silly in ‘Philippe Halsman’s Jump Book’

• Remembering September 11th: Photos of What They Left Behind