Search this site

Photography and Spirituality Intersect in John E. Dowell’s ‘Paths to Freedom’

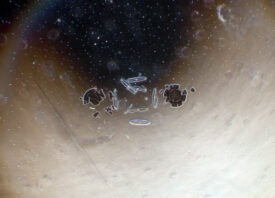

John E. Dowell’s hauntingly beautiful series, Paths to Freedom, originated from a dream featuring his long-departed grandmother and her tales of cotton fields. The dreams were so powerful that it encouraged him to seek out the cotton fields firsthand. In the deep South, in the dead of night, Dowell envisioned the harrowing journey of his enslaved ancestors. Through his photography, he explores their courage, wisdom, and pursuit of freedom amidst the darkness. His images, currently on view at The Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit, evoke portals, spirits, signs in nature, and faith.

The concept for your series originated from a dream. Could you share more about this? Did you wake up with a clear vision of what to create, or did it take time to piece it together?

“It took time to piece it together. When I first began having the dreams, I wasn’t quite sure what was being requested. After consulting with my sisters and brother, I assessed that it was about my grandmother’s stories of cotton.”

In your insightful conversation with Brittany Webb, you talk about your connection with your ancestors, specifically your grandmother. How hard was it to trust (and act on) what was being conveyed to you?

“My grandmother was very clear and matter-of-fact. From there it became a matter of how to get to the cotton—contacting farmers, traveling to farms, et cetera.”

Can you talk more about the idea of portals in nature offering hope and encouragement to

slaves? Was this something that you read about or something that you came by naturally when out in the fields? And in what forms (light, burrows, etc.) do you feel these portals existed?

“That idea of portals first came from my experiences with religions of African origin—Voodoo, Santeria, and Gullah spiritual traditions. In all of these experiences, the individuals

communicated with their ancestors, gaining informative guidance, strength, and the ability to survive. I almost always had emotional experiences photographing cotton. I experienced

hearing and seeing things that were there only on a metaphysical level. At times when I was out photographing, I could hear singing—and many times while I’m looking at cotton, I know nobody is there but I swear I can see slaves picking cotton. At rare times, I felt like I was really experiencing pain as if I had been beaten.”

For this series, you’ve photographed cotton fields in the dark. What did this process look like? Did you scout the location during the day and then go back at night with specific ideas? Or was it more of an organic process?

“A little of both. I started with an idea based on some exploration during the daytime, and then at dusk, I just followed a feeling. I sort of imagined the path and how a group or an individual would run away. Some of this was based on knowledge of the Underground Railroad and seeing or perceiving escape routes when I was within the cotton fields. When I was there at night, I got a certain feeling—it was an awareness of ancestral presence.”

So many of us are living in cities, addicted to screens, and disconnected from nature. I can’t help but think of the concepts of “grounding” or “earthing” when I see your work. Is that something that you think about? What do you think we can learn from nature, and what role does it play in your personal life?

“For me, I have looked for and searched for moments in nature that are very spiritual to me. In my work, I have discovered places and moments that have given that identification. For example, in a banana plantation in Caracas, I photographed an area that felt like I was in the middle of an altar. Not in front of it—I was in it. In South Dakota, I had a similar experience in a corn field where I felt the presence of God. So nature for me becomes a means of discovering my spirituality.

“When I am in nature and have removed all of the distractions of the world, I really feel a presence of God. What’s interesting for me is when I’m in the city, I feel there is a potential awareness of humanity in certain situations, like the park and areas of communication—what I really feel in the city is that disconnecting from screens and enjoying interactions with nature and individuals is possible. So that is to say these connections I experience in the city or outside the city are not formed in spite of a sort of addiction to the screen or an influence by that stuff—I just move through it—it’s not really a part of my life.”

Do you think there is a connection between being connected to nature and feeling connected to one’s ancestors?

“That depends on the experience and background of the individual. I think of experiences I have had in church services, ceremonies within the Gullah culture, Santeria, Voodoo, I could go on and on—all religions of the African diaspora where I’ve felt connected to my ancestors. In a ceremony of this sort there are many individuals who are possessed by spirits of ancestors. For example, in a Voodoo ceremony, one can have experiences with Shango or Ogun, and the same thing in Santeria or Candomblé. In the process of the ceremony, we can see someone who has been taken by the spirit of the particular Orisha or Loa. As I’ve mentioned, I’ve experienced connections to my ancestors in nature, I’ve experienced them alone, and I’ve witnessed others experience it in ceremonial or group environments—so it all depends on the individual.”