Search this site

Celebrate the Legacy of Irving Penn with “Centennial”

Irving Penn, American, Plainfield, New Jersey, 1917–2009, New York.

Pablo Picasso at La Californie, Cannes

1957, printed February 1985 Platinum-palladium print

Image: 18 5/8 x 18 5/8 in. (47.3 x 47.3 cm.) Sheet: 24 15/16 x 22 in. (63.3 x 55.9 cm.) Mount: 26 x 22 in. (66 x 55.9 cm.) Overall: 26 x 22 in. (66 x 55.9 cm.)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation IP .123

Irving Penn, American, Plainfield, New Jersey, 1917–2009, New York.

Three Asaro Mud Men, New Guinea

1970, printed 1976 Platinum-palladium print

Image: 20 1/8 x 19 1/2 in. (51.1 x 49.6 cm.) Sheet: 24 15/16 x 22 1/16 in. (63.3 x 56 cm.) Mount: 26 1/16 x 22 1/16 in. (66.2 x 56 cm.) Overall: 26 1/16 x 22 1/16 in. (66.2 x 56 cm.)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation IP .154

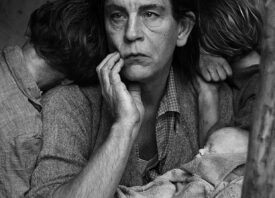

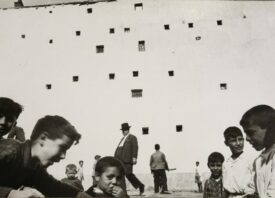

“Photography is just the present stage of man’s visual history,” Irving Penn (1917-2009) sagely observed, recognizing the infinite possibilities of the human animal to create technology that would advance our ability to document, represent, and re-envision the world. As a master of the form, Penn understood that the only thing that limits us is imagination.

For seven decades he worked, becoming a master of studio photography with the ability to craft pictures of anything he wished. Here was a man who could transform his very first commission for Jell-o pudding into a resounding success, even though, as Penn realized, it was, “a abstract nothing, it’s just a blob of ectoplasm.”

Yet with that formless glob of goop crafted in a laboratory, Penn was able to entice consumers to buy and serve the product en masse. It’s precisely this ability to transcend the particulars that made Penn a master of whatever form he chose to shoot, be in portraits, fashion, still life, food, nudes, or flowers. He understood that the photograph was an invitation to engage, to gaze upon the world without actually having to interact with it.

Through the safety of distance in time and space, Penn asked us to look at the complex and extraordinary beauty of existence in its many forms, whether Miles Davis’ hand, the Asaro Mud Men of New Guinea, or the curious silhouettes of Japanese designer Issey Miyake.

In celebration of the artist’s life, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, presents Irving Penn: Centennial, now on view through July 30, 2017. The exhibition follows Penn’s spectacular career, taking viewers on a magical trip through a life’s work that is unparalleled in photography. In conjunction with the show, the museum has produced an exhibition catalogue by the same name that is nothing short of phenomenal. With 365 color, tritone, and quadrotone illustrations, readers will lose themselves in Penn’s sumptuous imagery.

Looking at Penn’s work, one might think, “They don’t make them like this anymore,” but then a moment of reflection makes you realize talents of this magnitude come infrequently. Even Penn was aware of what was at stake, recognizing a moral obligation to create work that would stand the test of time.

While volunteering in the American Field Service in 1944-45, Penn’s time in Europe imbued him with a deeper, more lasting desire. In a letter to Alexander Liberman, Penn wrote, “Michelangelo is magnificent and Giotto is so simple. He seems to have decorated a church with considerably less commotion than we often make about a photograph. I am a little ashamed. If our age is to have a lasting art, its roots must be in a broad base of human understanding and need.”

This understanding is the golden thread that connects all of Penn’s subsequent work, whether creating haunting photographs of cigarette butts during the 1970s or crafting portraits of luminaries including Cecil Beaton, Colette, Pablo Picasso, Anais Nin, Alvin Ailey, and Zaha Hadid.

The amazing thing about a Penn photograph is the way he combined the magnificence of Michelangelo with the simplicity of Giotto, creating a perfectly composed image that stops you dead in your tracks and draws you in. Perhaps it was the understanding that his true medium was light, the way it fell on the flesh, on the cloth, on the surfaces of life. Light, that ever-changing elusive flow of energy that becomes electric when it comes into contact with whatever it falls upon, is Penn’s paintbrush and chisel, the tool he used to create these timeless icons of power and beauty.

Irving Penn, American, Plainfield, New Jersey, 1917–2009, New York.

Three Dahomey Girls, One Reclining

1967, printed 1980 Platinum-palladium print

Image: 19 11/16 x 19 11/16 in. (50 x 50 cm.) Sheet: 22 x 24 15/16 in. (55.9 x 63.4 cm.) Mount: 22 x 26 in. (55.9 x 66 cm.) Overall: 22 x 26 in. (55.9 x 66 cm.)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation IP .155

Irving Penn, American, Plainfield, New Jersey, 1917–2009, New York.

Naomi Sims in Scarf, New York

ca. 1969, printed 1985 Gelatin silver print

Image: 10 1/2 x 10 3/8 in. (26.6 x 26.3 cm.) Sheet: 11 x 10 13/16 in. (28 x 27.5 cm.) Overall: 11 x 10 13/16 in. (28 x 27.5 cm.) Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

IP.112

Irving Penn, American, Plainfield, New Jersey, 1917–2009, New York.

Glove and Shoe, New York

July 7, 1947 Gelatin silver print

Image: 9 9/16 x 7 3/4 in. (24.3 x 19.7 cm.) Sheet: 9 9/16 x 7 3/4 in. (24.3 x 19.7 cm.) Mount: 11 15/16 x 10 1/16 in. (30.3 x 25.6 cm.) Overall: 11 15/16 x 10 1/16 in. (30.3 x 25.6 cm.)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation IP .075

Irving Penn, American, Plainfield, New Jersey, 1917–2009, New York.

Irving Penn, American, Plainfield, New Jersey, 1917–2009, New York.

Two Miyake Warriors, New York

June 3, 1998, printed January-February, 1999 Platinum-palladium print

Image: 21 x 19 5/8 in. (53.4 x 49.8 cm.) Sheet: 23 1/4 x 21 9/16 in. (59 x 54.7 cm.) Mount: 23 1/4 x 21 9/16 in. (59 x 54.7 cm.) Overall: 23 1/4 x 21 9/16 in. (59 x 54.7 cm.)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation IP .166

Irving Penn, American, Plainfield, New Jersey, 1917–2009, New York.

Irving Penn, American, Plainfield, New Jersey, 1917–2009, New York.

Marlene Dietrich, New York

November 3, 1948, printed April 2000 Gelatin silver print

Image: 10 x 8 1/16 in. (25.4 x 20.4 cm.) Sheet: 10 x 8 1/16 in. (25.4 x 20.4 cm.) Overall: 10 x 8 1/16 in. (25.4 x 20.4 cm.) Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

IP .105