Search this site

The Man Who Made History by Photographing India in Color

Raghubir Singh, Ganapati immersion, Chowpatty, Bombay, 1989

Chromogenic print

Photograph copyright © 2017 Succession Raghubir Singh,

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

Raghubir Singh, Holi revellers, Bombay, 1990

Chromogenic print

Photograph copyright © 2017 Succession Raghubir Singh,

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Raghubir Singh (1942-1999) secured his position as one of the early serious photographers to work in color. At the time, Kodachrome slide film was not generally accepted by his contemporaries in Europe and the United States, but Singh felt it was necessary to his life and purpose as a photographer of India. Unfortunately, it wouldn’t be available in his home country until trade restrictions were lifted in the early 1990s. In the meantime, Singh relied on magazines overseas, including National Geographic, to provide him with the precious film he had nicknamed “King Kodachrome.”

Now, Singh’s electric street photographs, described by Mia Fineman of the Metropolitan Museum of Art as “teeming with incident”–are in New York in two coinciding exhibitions: Raghubir Singh: Bombay at Howard Greenberg Gallery and Modernism on the Ganges: Raghubir Singh Photographs at the Met Breuer.

Singh first met Henri Cartier-Bresson in 1966, when he was twenty-three years old, and the elder photographer became a lifelong influence. But, as Fineman writes in this exhibition catalog, they chose divergent paths in a number of ways. Firstly, Singh photographed in color, a choice that became a signature, and secondly, Singh in some sense did away with Cartier-Bresson’s famous notion of that one, single “decisive moment.” In a Singh photograph, the movement is never frozen by being made still.

Both of these decisions were rooted in Singh’s sense of place. “The fundamental condition of India,” he wrote, “is the cycle of rebirth, in which colour is not just an essential element but also a deep inner source, reaching into the subcontinent’s long and rich past.” In India, time never stopped, even when someone clicked the shutter of a camera. Amusingly, Josef Koudelka once claimed Singh’s photographs were “too much about the places.” As Fineman tells it, Singh responded by saying, “That’s funny, because I think your pictures are not enough about the places.”

Singh borrowed from Indian art history and married it with the themes and motifs that defined street photography in Europe and America. He used two seemingly disparate fields, and by some sort of alchemy, he fused them to create his own. Following the artist’s death, Max Kozloff of Aperture wrote, “If you imagine what a Rajput miniaturist could have learned from Henri Cartier-Bresson, you’ll have a glimmer of Raghubir Singh’s aesthetic.”

Singh once explained his love for photography this way: “My heartbeat ran an umbilical cord to my camera.” Sadly, he passed away of a heart attack at the age of fifty-six, but we can find him reborn in the images he left behind. Perhaps here, in streets of Singh’s India, a heart still beats.

Raghubir Singh: Bombay at Howard Greenberg Gallery includes 28 photographs made by the artist in the 1990s–during the later part of his career. It will remain on view through December 9th, 2017. Visit the coinciding exhibition, Modernism on the Ganges: Raghubir Singh Photographs, at the Met Breuer through January 2nd, 2018.

Raghubir Singh, Muslim Girl, Nagpada, Bombay, c. 1990-1993

Chromogenic print

Photograph copyright © 2017 Succession Raghubir Singh,

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

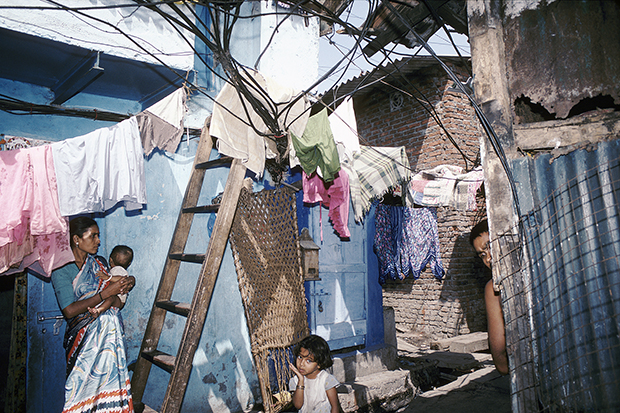

Raghubir Singh, Mother and Child, Dharavi, Bombay, c. 1990-1993.

Chromogenic print

Photograph copyright © 2017 Succession Raghubir Singh,

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

Raghubir Singh, Showroom at Kemp’s Corner, Bombay, c. 1990-1993.

Chromogenic print

Photograph copyright © 2017 Succession Raghubir Singh,

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

Raghubir Singh, Playing ‘Punishment’, a marble game, Bombay, 1991

Chromogenic print

Photograph copyright © 2017 Succession Raghubir Singh,

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery