Search this site

Strength and Humility in the Photographs of Dorothea Lange

Paul S. Taylor. Dorothea Lange in Texas on the Plains, ca. 1935

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Dorothea Lange. Drought Refugees, ca. 1935

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

In 1902, at the age of seven, Dorothea Lange (1985–1965) was stricken with polio. Left with a withered foot and a permanent limp, Lange’s next challenge came at the age of 12, when her father abandoned the family. These early traumas formed and shaped Lange, forcing her to become self-reliant at a young age.

While in high school, Lange determined that she would become a photographer, though she had never used a camera before – but she made moves, studying the medium with Clarence H. White at Columbia University. She honed her skills on the streets of New York, recalling, “On the Bowery I knew how to step over drunken men. I knew how to keep an expression of face that would draw no attention, so no one would look at me. I have used that my whole life in photographing.”

In 1918, Lange and a close friend decided they would see the world, so they jumped in a car and headed West. The international leg of their trip was aborted in San Francisco, after they were robbed. Lange quickly fell in with the local photo scene, secured financial backing, and set up her own photo studio where she created portraits of the city’s bohemian and artistic elite. But when the Great Depression hit, everything changed – and the story of Dorothea Lange comes to center stage. The discrepancy between what was happening in her studio versus the reality f the streets became more than the artist could bear, and she decided to be the change she wanted to see in the world.

In Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing (Prestel), author Alona Pardo has created a stunning visual biography that provides an incredible survey of Lange’s career, providing a rich and nuanced look at the political power and impact of photography of the way we see, think, and feel. The book takes us through the Dust Bowl, heading into Texas and Mississippi to look at African Americans living in apartheid conditions under Jim Crow, before circling back to California to document life for Japanese Americans who had everything taken from them before being forced into concentration camps.

“One should really use the camera as though tomorrow you’d be stricken blind,” Lange said, “To live a visual life is an enormous undertaking, practically unattainable, but when the great photographs are produced, it will be down that road. I have only touched it, just touched it.”

But the delicacy of Lange’s touch is heightened by the specificity of the narratives she chooses to portray. As the only woman photographer working in the Farm Security Administration, Lange’s perspective is invaluable, for her eye was drawn to stories that no one else saw. Amid the iconic photographs of the Depression and the Dust Bowl, Lange’s float above, for though hers is a hard-luck story, it is never insurmountable.

In Lange’s photographs, the road ahead is long and dry, but it is matched by a grim determination that underscores the fight to survive. The people of Lange’s photographs never say die – though they assuredly have more than a few words that tell it like it is.

Lange’s approach strongly differed from that of her contemporaries. To make her photographs, Lange recalled, “Sitting on the ground with people, letting the children look at your camera with their dirty, grimy little hands, and putting their fingers on the lens, and you let them, because you know that if you will behave in a generous manner, you’re very apt to receive it.”

This mutuality was driven in large part by Lange’s understanding of the collaborative nature of the photograph. She revealed, “I never steal a photograph. Never. All photographs are made in collaboration, as part of their thinking as well as mine.”

Lange’s fundamental humility and respect for her subjects has imbued her work with a profound depth of humanity that is as impressive now as it was when these photographs were made. Lange, in many ways, is a progenitor to the famed slogan, “The personal is political,” for she understood just how to use the truth to provoke not only empathy and understanding but wisdom and knowledge.

“If you can come close to the truth, there are consequences from the photograph,” Lange observed. The ultimate value of the photograph is greater than the sum of its parts. For Lange, “There is an element which you can’t call other than an act of love. That is the tremendous motivation behind it. And you give it. Not to a person, you give it to the world… an act of love – that’s the deepest thing behind it… The audience, the recipient of it, gives it back.”

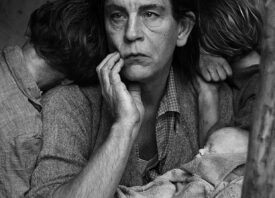

Dorothea Lange. Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, 1936

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Dorothea Lange. Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona, 1940

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

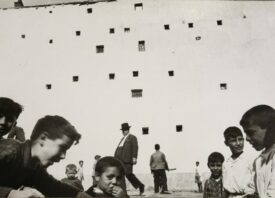

Dorothea Lange. Sacramento, California. College students of Japanese ancestry

who have been evacuated from Sacramento to the Assembly Center, 1942.

Courtesy National Archives, photo no. 210-G- C471

Dorothea Lange. Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. An evacuee

is shown in the lath house sorting seedlings for transplanting.

These plants are year-old seedlings from the Salinas Experiment Station, 1942.

Courtesy National Archives, photo no. 210-G- C737

Dorothea Lange. White Angel Breadline, San Francisco, 1933.

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

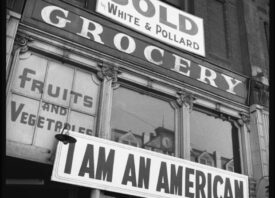

Dorothea Lange. Centerville, California. This evacuee stands by her baggage

as she waitsfor evacuation bus. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in

War Relocation Authority centers for the duration, 1942.

Courtesy National Archives, photo no. 210-G-C241