Search this site

A Powerful Portrait of Living Off the Grid in Northern Canada

A view of Yellowknife Bay from Jolliffe Island.

Ryan and Cheyanna on Jolliffe Island.

Deep in the Northern Territories of Canada, on the edge of Great Slave Lake lies a community living off the grid, on the fringes of Yellowknife, the capital city — home to photographer Pat Kane, a member of the Timiskaming First Nation.

The city of Yellowknife, named for a local Dene tribe, first colonized in the 1930s after gold was discovered. Early prospectors headed north, erecting shacks and shanties on the waterfront, which remained intact as the city was built around these settlements.

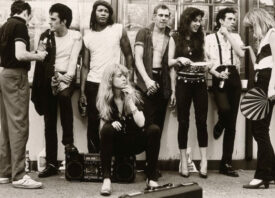

By the 1980s, the first houseboats appeared on the lake, and together, with the shacks, became home to a flourishing community who have chosen the solitude of nature over the conveniences of modernity. In his on-going series, Offgrid, Kane documents a colorful collection of characters from all walks of life — from musicians and artists to bureaucrats, entrepreneurs, and curmudgeons — whose back-to-basics way of life has become a vibrant part of the city’s cultural landscape.

Here, Kane shares his experiences photographing the people who live in this magical corner of the world.

Phil Boscariol takes a break from reparing his floats underneath his houseboat rental.

Could you speak about being a member of the Timiskaming First Nation, and how this informs the kinds of stories you explore as a documentary photographer working in Canada?

“My mother was born and raised on a reservation in Quebec, which is part of the Timiskaming First Nation, and she encouraged me to learn about our family and our Algonquin heritage growing up. When we visited there, it was quite different from my life in the city. We went fishing and played outside in the bush a lot.

“These experiences helped me stay in tune with nature, which I think informs a lot of the projects I do now in Canada’s North. I work in many of the smaller communities throughout the Northwest Territories and I feel very comfortable with the Dene, Gwich’in and Inuvialuit people who call this region home. A lot of my documentary work focuses on the issues facing indigenous people in Canada’s North. Living here has actually lead me to feel more connected to my indigenous heritage, something I didn’t always appreciate, especially in my teens.

“My Offgrid project is actually very different from my other work but I’m still exploring themes of people and their connection to the land in this series.”

Dryfish hangs on a string in Blake Rasmussen’s boat.

The fisherman sells his catch on the dock at Yellowknife Bay.

How did you first learn about Yellowknife, and what inspired you to move there in 2005?

“Yellowknife is one of those cities that all Canadians learn about in grade school geography class, but is a place that few have ever visited. It has this last-frontier-town vibe entrenched in the national consciousness, kind of like how Americans think about Alaska as this big, inhospitable, sparsely populated, cold, lawless hinterland.

“I moved to Yellowknife in 2005 as a short adventure to say I went North. Like most of the people who live here, I told myself I’d stay for a year and I’m still here almost fifteen years later. It’s a city that hooks you. The diversity of people, the opportunities to work interesting jobs, the sense of culture and history — it was not at all what I expected and I fell in love with the place.”

Could you describe the landscape, and the allure of being in nature, removed from the perils of “civilization”?

“Yellowknife is home to 20,000 of the 40,000 people that live in the Northwest Territories, which has an area twice the size of Texas. The landscape is very diverse: huge mountains to the west, barren tundra to the north and the east, the Arctic Ocean to the north.

“In Yellowknife, lakes and rivers pockmark the landscape and tiny, robust trees grow out of the rocky outcrops in and around the city. It takes about five minutes to find a lake in any direction so a lot of the people play, work and live on the water. The nearest major city is Edmonton, Alberta, which is about 1,000 miles to the south. It’s easy to feel isolated but at the same time it is very peaceful and we have a ton of fun, especially in summer when there is 20 hours of daylight.”

Tom Parker paddles to his houseboat during freeze-up on Yellowknife Bay.

Could you describe the qualities of the people who live in this community that make it unique?

“The people in Offgrid have a lot of different traits and personalities and interests but I think at the heart of it, they are all adventurers. Whether they built their shacks themselves or are renting it, they all like the appeal of living there. Some readers might look at the pictures and think they are all the hippies who live in a commune, but this is not true.

“They all have very different backgrounds and stories. Some are government workers, others are engineers, a few work in the diamond mines, some are teachers, electricians, musicians, office workers and lawyers. They are simply regular folks who find it fascinating (or economical) to live in a rustic shack in the North.”

How has the community been misrepresented by the media, and why do you think this is?

“When you first come to Yellowknife, one of the first things that stand out are the houseboats, the shacks and the people who live there. It’s easy to see them as stereotypical Canadian hosers like Doug and Bob Mckenzie (there are a lot of plaid jackets and big rubber boots around, and I’ll explain why: it is cold and wet!).

“That said, there have been TV productions and magazine articles that focused exclusively on the goofy slack-jaw yokel caricature that you also see in films set in the American Midwest. I’d be lying if I said there aren’t any comparisons to the off grid community in Yellowknife but by and large the people are much more interesting and nuanced than the stereotypes they’re portrayed as.”

Tom Parker, Katie O’Beirne and their baby, Patrick, outside of their houseboat.

How is it that the community is allowed to live tax-free?

“It’s inaccurate to say that houseboaters live tax-free. They all pay income tax just like everyone else does. They simply do not pay some property tax to the City of Yellowknife because their homes are not on City property. Technically, they are squatters on federal or indigenous land and water.

“Basically, all the tax-free stuff means is that nobody is collecting their garbage and they aren’t connected to the electrical grid so they have to do this all themselves. Not many people can say they charge their iPhones using solar energy and shit into a garbage-bagged bucket, but most of the people here do.”

What would you like the public to understand about the community and their contribution to the culture of Yellowknife?

“One of the best things about the people who live in the shacks and houseboats is that they contribute so much to the fun and activity of Yellowknife. Every March, a crew of houseboaters build a massive castle of ice and snow on Yellowknife Bay. It’s called the Snowcastle and it was started 24 years ago by Anthony Foliot who goes by the name Snowking during the festival. It draws in tourists from all over the world. That is just one thing.

“Throughout the year, the off grid community is involved in all sorts of Yellowknife events: the Folk on the Rocks Music Festival, the Dead North Film Festival, various art exhibits, installations, you name it. They are a key part of Yellowknife’s identity.”

Shawn Buckley and Pierre-Benoit Chalifoux navigate through half-frozen water

on Yellowknife Bay.

Stephanie Vaillancourt chips the ice free from her water hole that she relies on for cleaning.

Rylund Johnson takes a dip in his water hole at minus-40 Celsius.

Courtney Mckiel helps build an Ice Castle for children and tourists on Yellowknife Bay.

Brian Bill in his shack on Jolliffe Island.

Houseboaters have a winter bonfire on the ice celebrating the winter solstice, December 21st. At this time of year the sun rises at about 10am and sets at 2pm.

All images: © Pat Kane