Search this site

Carrie Mae Weems Presents a Visual Symphony in Five Parts

Carrie Mae Weems, Slow Fade to Black (Nina Simone), 2010.

Carrie Mae Weems, Color Real and Imagined, 2014.

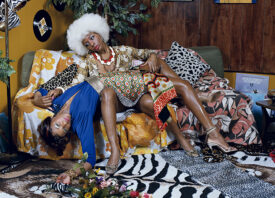

Carrie Mae Weems, Anointed, 2017.

When Carrie Mae Weems made The Kitchen Table Series in 1990, she centered the intimate lives of Black women on the world stage, asserting the importance and impact of these tender moments of family and self-love at the very heart of her photographic practice. Her self-portraits were constructions of intergenerational experiences rooted in knowledge of self and the power of identity when made visible and centered as the basis for a work of art.

Weems’s practice in one rooted in knowledge of self, of the visceral need to create art and share it with the world. It is something that is done for the act, rather than the ends — and in this way it withstands the test of time, never falling prey to fads or trends.

“I don’t make work for the market. I create out of necessity, and so in one strange way, if we were to look at how my work might be received at Sotheby’s or at Christies when it goes up to auction, there’s frankly very little interest in my work,” Weems reveals in an interview with canadianart. “It has been historically undervalued. I think that most people are interested in beautiful things that don’t necessarily cause them to think very deeply about any one thing.”

Liberated from the constrictions of feeding the capitalist enterprise, Weems’s work has become a testament to the power of independence and self-reliance. As the featured artist at the 2019 Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival in Toronto, Weems has created a symphony in five parts: “Heave” at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto, “Blending the Blues” at the CONTACT Gallery, and the public installations “Scenes & Take,” “Anointed” and “Slow Fade to Black” across the city through July 27, 2019.

The public installations are marvels of the disruptive powers of beauty and the way in which they inform our sense of self and our place in the world. In “Slow Fade to Black” (2010), Weems brings together 13 larger-than-life portraits of artists and icons including Josephine Baker, Nina Simone, Leontyne Price, Dinah Washington, Mahalia Jackson, Shirley Bassey, Ella Fitzgerald, Abbey Lincoln, Eartha Kitt, Koko Taylor, and Katherine Dunham.

Rendering black and white, the portraits glisten and glow, light emanating from deep within like the eternal soul. Installed in a straight line at Metro Hall, the portraits come into focus the further you step back and see them together as a group: those who defied all circumstance to attain legendary status worldwide. It’s easy to imagine how vast the group could become were the barriers to access and entry removed from the systems that actively work against race, gender, sexuality, class, age, and ability.

Weems balances grandeur and intimacy with ease, as her series “Blending the Blues” reveals over a three-decade span. Here, the artist uses color as a metaphor for Blackness, giving us the full spectrum of human experience: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Here, the blues are the heart and soul of a people and an art, offering an aesthetic means to process the unspeakable horrors perpetrated upon African Americans over five centuries on this land.

Carrie Mae Weems, Low Brown Boy, from the series Colored People, 1989–90.

Carrie Mae Weems, Magenta Colored Girl, from the series Colored People, 1989–90.

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Colored People Grid), 2009.

Carrie Mae Weems, Slow Fade to Black (Eartha Kitt), 2010.

Carrie Mae Weems, Slow Fade to Black (Shirley Bassey), 2010.

Carrie Mae Weems, Slow Fade to Black (Dinah Washington), 2010.

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Spike Lee Grid), 2018.

Carrie Mae Weems, All the Boys (Blocked 3), 2016.

All images: © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, NY.