Search this site

An Intimate Look at the Secret Life of April Dawn Alison

“Everyone has three lives: a public life, a private life and a secret life,” the novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez knowingly remarked, reminding us that what we see and what we believe is often just an illusion of sorts. Beneath it all, lays the true self, an identity we often keep hidden from the world — including ourselves.

But there are those who dare to delve into the person they are we no one else is there to witness it. These moments are a manifestation of something beyond the person others see: it is the self that exists within our deepest being. To record this, to document it, to create evidence of that which exists for no one else — this takes nerve. It is here our story of April Dawn Alison begins.

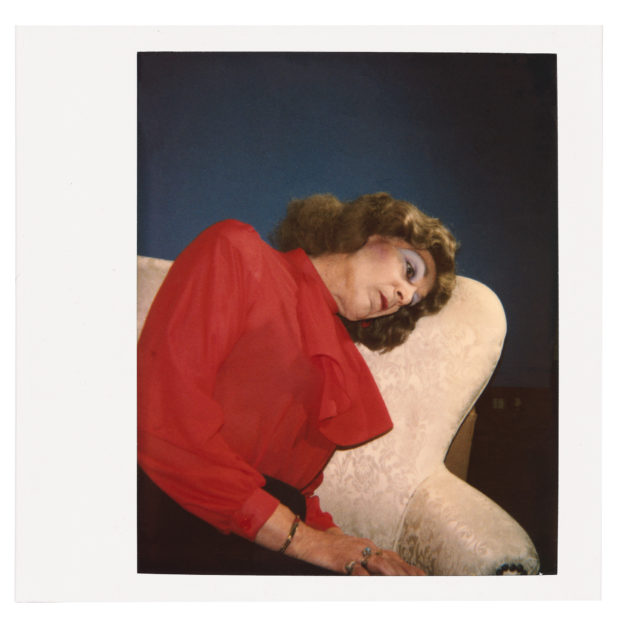

In 2017, a painter named Andrew Masulio donated an archive of over 8,000 Polaroids to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) — previously unseen self-portraits of April Dawn Alison, the female persona of Alan Schaefer (1941-2008), an Oakland-based photographer who lived in the world as a man. The archive reveals to us a fully-realized secret life beautifully revealed in the exquisite monograph, April Dawn Alison (MACK), selections from which are currently on view at SFMOMA through December 1, 2019.

Hailing from the Bronx, Schaefer learned photography in the military, loved jazz and tennis, and worked as a billboard photographer. Author Erin O’Toole notes in the book’s introduction that family members were aware that Schaefer sometimes donned women’s clothes and neighbors were prone to gossip about his practice, though no one truly knew that April Dawn Alison was her own person.

When Schaefer died alone at home at the age of 67, April Dawn Alison was finally discovered and recognized. She simply would not, could not be destroyed. She was an all-consuming creation of Schaefer’s deepest heart, a woman of many moods and guises with a love for bondage.

Although not classically beautiful, April Dawn Alison was a goddess and a vamp, a sexual, sensual, sophisticated lady who loved to don costumers and wigs, posing in front of the camera ready for her close up like Norma Desmond. She was a being of the golden age of Hollywood, perfectly coiffed even when she was tied to a chair.

Perhaps Schaefer’s experiences working as a billboard photographer provided him with a complex lexicon of feminine archetypes for every mood. It is evident that the camera provided a space for expression and recognition in equal part. The photographs collected here are a testament to the old saying, “Seeing is believing.”

April Dawn Alison was made to be seen, for Schaefer kept her alive, making Polaroid after Polaroid, and released her into the world upon his death, giving to us what he cherished, secretly for himself. He clearly took pleasure in expressing the woman within in her various emotional states, an intense, erotic, and playful being that simply loved the accoutrements of feminine glamour and vanity as a means to tapping into the inner self. Each session features multiple poses so that we have a 360 degree view of the full being: a day in the life of April Dawn Alison, month after month, year after year.

“Publishing the private work of a deceased person raises many open questions surrounding privacy and intent, but after much reflection and discussion with friends and family of the artist, I have come to believe that the deep humanity, emotional impact, and visual sophistication of these photographs demands that they be shared,” O’Toole writes.

It’s difficult to disagree with this assessment — there’s something in April Dawn Alison that yearns to be free, to live in the public world, finally.

All images: © April Dawn Alison, Untitled, n.d.; San Francisco Museum of Modern art, gift of Andrew Masullo. Courtesy of SFMOMA and MACK