Search this site

An Intimate Look Inside Saul Leiter’s East Village Art Studio

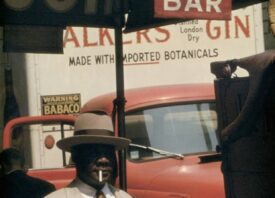

In 1952, American photographer Saul Leiter set up a studio on East 10th Street back when the East Village was just that – an obscure outpost for bohemian life that drew artists, jazz musicians, beatniks, and other bon vivants who sought affordable rents so that they could live and make art.

Leiter, who was making his name as an integral figure in the New York school of photography that includes Helen Levitt, Lisette Model, Weegee, Robert Frank, and Diane Arbus, embraced the tough-minded humanism of city life that allowed him to create sharp, telling encounters along the streets of New York.

But up in his studio, something else was taking place — a quiet, contemplative series of black and white nudes made over a period of 30 years wholly unlike the fashion shots he made for the pages of Harper’s Bazaar, Esquire, and Elle. “It’s almost like they were a relief from his professional work,” writes Carole Naggar in the introduction to Saul Leiter: In My Room (Steidl).

Here, in an intimate monograph. Leiter’s work is presented for the first time, allowing us a glimpse into his private world, where he went to escape it all. Leiter invited long time friends and lovers into this realm and they shared moments reveal another layer to Leiter’s gifts.

The artist, who preferred to be left alone, worked in relative obscurity until his 80s, the last decade of his life, playing all his cards very close to the vest. He resisted explaining or analyzing his work, allowing the photographs to speak for themselves. This makes the images something of a Rorschach Test, inviting us to look inside and reflect upon what his work triggers in us.

Born into an Orthodox Jewish family, Leiter trained to be a rabbi like his father until 1946, when he moved to New York to become a painter. When he finally decided to be a painter, his father was appalled. “My dream was that you would be a Chekhov. Then, okay, maybe a Chagall. But a photographer!”

Leiter’s father disowned and disinherited him, and Leiter was left to fend for himself, relying on his talents without turning himself into a brand and selling out. Instead he simply continued along his path. Although Leiter never showed anyone the nudes, in the 1970s, he began to plan out a book — though the project was not realized prior to his death in 2013. Instead, he left the works to us, his secrets kept, so that all we have to consider are the photographs.

“Leiter’s gaze is not that of the typical male,” Naggar writes. “The women can in turn be shy, aggressive, or playful, but they always appear to be partners and full participants in a give-and-take, a dialogue, very aware of the photographer and the photograph that is being taken. In other words, these are not traditional nudes but rather portraits of women who happen to be in the nude.”

They are subject, not objects, not extensions of the photographer’s ego. They are not reduced to the realm of muse, a romantic notion at best, but rather treated as co-collaborators in the creation of the image. They are individuals, rather than archetypes. Women whose voices are expressed in gesture and expression, so that their beauty is not merely skin deep.

In the book’s afterword, Richard Benton makes it clear: “The women in these photographs are unguarded; they are naked, not nude, not clothed with the invisible garb of ‘art.’ They are just out there, these women, frail and beautiful and deeply human. I look at this book and I know exactly why Saul spent his life taking photographs of them.”

All images: © Saul Leiter Foundation, courtesy of Steidl.