Search this site

Welcome to Kowloon Walled City, One of the Most Misunderstood Places in History

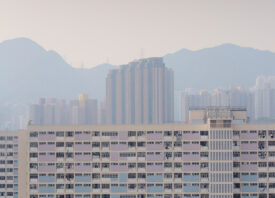

When the photographer Greg Girard first ventured into Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong in 1986, he didn’t take any pictures. Instead, he simply absorbed the sights, sounds, and smells that surrounding him on all sides: illuminated windows, densely packed across 12-14 story buildings, voices from televisions and the hum of fans and air conditioners filling the streets.

But Girard returned to the “city,” again and again, over the course of about four years, and so did his fellow photographer and writer Ian Lambot. They were drawn to the settlement independently, and as they were among just a few covering in the area, they ultimately joined forces to tell the story of this mysterious and idiosyncratic place–far and away the most densely populated urban area in the world, with an estimated 603 people per 5,000 square feet.

By 1988, they added Emmy Lung, a recent graduate from Hong Kong University, to their team, and she embarked on a series of interviews with the city’s residents. The book City of Darkness: Life in Kowloon Walled City, first hit bookshelves in April of 1993, shortly after demolition began on the settlement. Twenty years later, Girard and Lambot released City of Darkness Revisited, underscoring the timelessness and enduring legacy of this singular community.

“Seeing it for the first time, and taking those first tentative steps inside, was unforgettable,” Girard remembers. “Fascination and dread in equal measure.” While it stood, Kowloon Walled City had a fearsome reputation, fueled by rumors and due in part to its limited oversight and regulation. Because the city was so dense, and the streets so narrow, it was dark at almost all times of day.

Still, the photographers became familiar with the community and its members. Often, they were met with open doors as they navigated those tight alleyways, permitted to peer into dentists’ offices and doctors’ clinics, factories and workshops. Some sights were grisly and difficult to stomach, but others were strangely beautiful and exhilarating.

“The workshops dealing with food preparation were often quite extreme: animal carcasses on a wet floor, men burning the hair off with blowtorches,” Girard remembers. “Going from that to the air and light and space on the rooftop in the cool of the evening, watching the big jets arc past on their way into Kai Tak [airport], that was incredible as well.” The planes passed overhead approximately every ten minutes–limiting the buildings to a height of 14 stories for fear of collisions.

Kowloon had its fair share of vices, many of which have been covered extensively, but in this book, we learn that it was also home to schools, kindergartens, and religious institutions; the community had a barber shop, a weaving factory, a candy shop, and even a senior center. By the time Girard and Lambot entered the scene, many of the locals were aware of the impending change. “It was understood that the Walled City’s days were numbered and [we] were there to make a record,” Girard remembers.

He and Lambot try not to romanticize a location where life was difficult and conditions were poor, but they do insist that Kowloon was more than anyone at the time expected it to be. For many, despite its shortcomings, it was a place to call home, at least for a while.

“All my children were born here; they were married here,” a grocery store owner, who had been in business in Kowloon for forty years, told them once the demolition had been announced. “They can pull everything down, but the demolition of the Walled City isn’t the same as getting rid of ordinary squatters. The whole world will know about it.”

Today, the space is unrecognizable. “The environments where the Walled City once stood have changed dramatically in the 26 years since the City’s demolition,” Lambot explains. “The site itself has changed immeasurably, with all indications of what was once there almost totally eradicated and replaced with a simulation of a traditional Chinese magistrates garden.”

City of Darkness Revisited isn’t a nostalgic testament to Kowloon, but it doesn’t have to be. For a place like this, a city neglected and overlooked, ignored and cast aside, any kind of recognition–even an unsentimental one–is enough. This city, where daylight entered only in patches and dank moisture pervaded the streets, was flawed and complicated, but it was also extraordinary.

Girard admits, “There are many places I would like to photograph, but I don’t expect to see anything like the Walled City again in my lifetime.” That grocer was right; the whole world knew when Kowloon was demolished, and the whole world remembers it still. Find the book, updated and revisited, here. The work is represented by Monte Clark Gallery in North America and Blue Lotus Gallery in Hong Kong.